Helen O’Shea: No better boy: listening to Paddy Canny, Dublin, Lilliput Press, 2023

ISBN: 9781843518655

RRP: €25.00

Copies available in Australia at a discounted price by emailing the author, helenfoshea@gmail.com

Review by Matthew Horsley

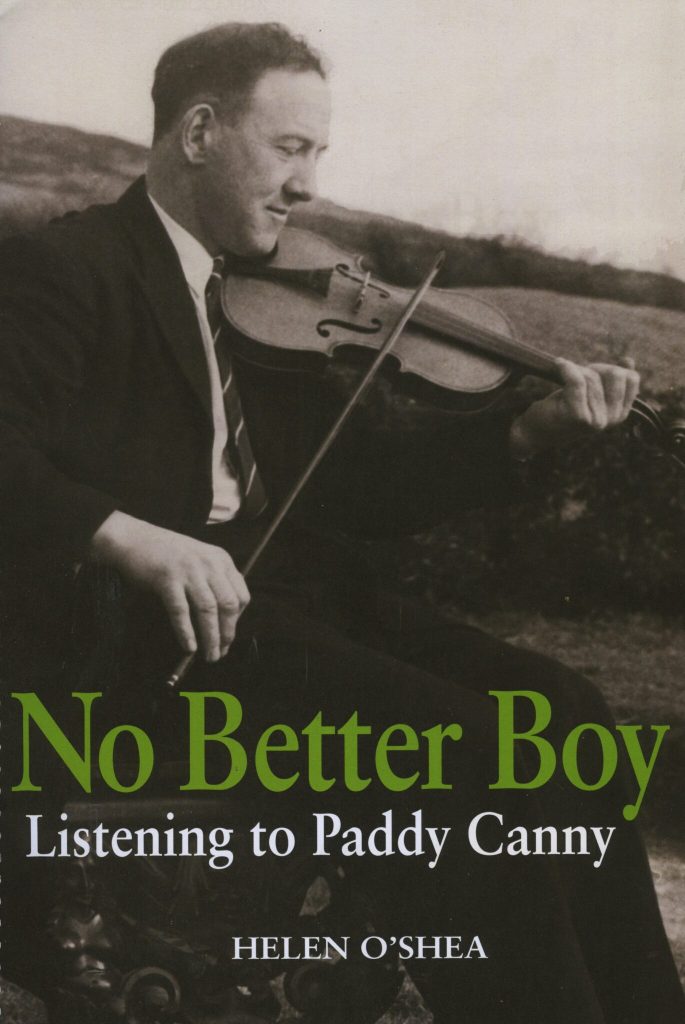

The name Paddy Canny (1919 – 2008) will be familiar to many involved with Irish traditional music – a legendary exponent of the East Clare fiddle tradition, a founding member of the no less legendary Tulla Céilí Band, a profound influence on countless Irish fiddlers to this day. Those who can draw on sonic as well as historical impressions will possess other associations – the achingly long slides into plaintive pitches somewhere between the cracks of the piano keys, the subtle use of crescendo and decrescendo to emphasise a surprising new facet of even the most familiar tune, a “quiet comfort and beauty” (p. xi) that invites the listener to explore ever-changing interior landscapes.

Australian author, scholar and fiddler Helen O’Shea’s No Better Boy provides a profound and compelling picture of Canny’s life and music, accessible to non-musicians and musicians alike. The book is arranged as a series of episodic reflections, the majority occupying fewer than three pages, complemented with photographs and musical transcriptions. The topics of these episodes range from Canny’s repertoire and recordings to the broader history of the locality and the minutiae of daily life in East Clare. This sometimes disorienting change of focus refuses to acknowledge music as a separate or rarefied realm of human endeavour, the rhythms of Canny’s bow fading into the cycles of rural Irish life, personal joys and sorrows and the broader historical sweeps of war, emigration and social change. O’Shea’s prose style bears a certain kinship to Canny’s music, at once lyrical and economical, sometimes eliding information to allow the reader to craft their own impression, at other times focusing minutely on a detail which would have otherwise gone unremarked.

O’Shea’s opening sentence leaves no illusions as to her intentions – the goal is not biography or documentation as such, but to tell ‘stories based on the life of … Paddy Canny’ (p. i). The creative approach becomes immediately evident when we are made privy to Canny’s thoughts and emotions – a time-honoured device for the storyteller, but anathema to many historians. And yet, what work of history is completely devoid of the author’s fingerprints? At the same time, there can be no doubt that this a meticulously researched piece of writing, drawing on dozens of interviews with Canny, his family, colleagues and neighbours. A large proportion of these were conducted by O’Shea herself and given the paucity of written material on the subject, her diligence as an oral historian must be applauded. The book provides an index and bibliography but no citations throughout. This is certain to irritate those wishing to locate the source for a particular piece of information, or even know exactly how far O’Shea’s creative liberties extend. But these are concerns for the scholar, not the storyteller; here, a certain trust is asked of the reader, offering the possibility of an intimacy and vulnerability unachievable in academic writing.

Where O’Shea’s previous book, The Making of Irish Traditional Music delivered a trenchant critique of the processes of mythmaking around Irish traditional music favoured by music industry executives, tourism boards and national cultural institutions, No Better Boy at times seems to point towards its own kind of mythology. O’Shea’s command of narrative and imagery leaves such a profound emotional impact that the reader is frequently tempted to impose their own meaning on Canny’s life and music, whether a tale of personal triumph over adversity, a celebration of an enigmatic musical visionary who refused to bow to others’ expectations or an anxious commentary on more recent currents in Irish traditional music. Clearly aware of this possibility, O’Shea has been very careful to afford her subject a fundamental dignity and agency, to “avoid foundering on the rock of scepticism or being sucked into the whirlpool of sentimentality” (p. viii). For all the book’s detail and lyricism, there is something about Canny that remains mysterious and irreducible, always encouraging the reader to listen further.

One of the most interesting aspects of the book is its depiction of the series of technological and cultural revolutions that reshaped Irish traditional music in the 20th century and in many ways still agonise musicians today. While these topics have been considered in depth in various publications (including O’Shea’s previous book), the focus on an individual life lived at the brink of these changes offers a uniquely human perspective, able to gaze backwards and forwards in time. Immersed in the local repertoire and style of his father, Canny was to have his musical universe exploded through the arrival of the 78rpm phonograph recordings of Michael Coleman and other Irish-American musical luminaries (‘fallen like a meteor into Paddy’s world’, p. 59) in the hills of East Clare. This tension between local and cosmopolitan musical influences is played out throughout Canny’s life. It is perhaps most poignantly expressed when he gets the opportunity to introduce his father’s tunes, embellished with the virtuosity and sophistication he discovered in Coleman’s recordings, to an enthralled New York audience in the 1950s. If this captures some of the optimism of the new age, the exclamation of dismay – ‘Poor Paddy! He’s been taken!’ (p.127) – from an elderly neighbour upon seeing Canny performing on the television evokes the rupture and uncertainty that technological and social change brought to rural Ireland. Similarly, the advent of professional musicianship in what was previously a communally oriented musical culture is thrown into focus, as Canny struggles to reconcile his life on the land and his ties to family and place with the long days spent on the road to céilís, recording studios and concert appearances.

No Better Boy will find a natural readership amongst musicians and scholars of music, but non-musicians should not feel any trepidation in approaching it. Almost half of the episodes do not directly mention music, and anyone interested in Irish social and cultural history will find much to appreciate here, perhaps even learning a little more about the Irish musical tradition in the process. Even when tunes or recordings are the chief focus, O’Shea studiously avoids the excessive use of jargon, instead relying on descriptive language which emphasises meaning over technique. The detailed transcriptions will be appreciated by those who read music, but their significance is always clearly explained for other readers.

The black-and-white photographs, on the other hand, often lack the impact they could have possessed. The image quality of historical and recent photos alike has been degraded in publication, sometimes projecting a sense of distance on subjects that the writing is working to draw the reader closer to. In a book whose large size and attractive layout recommend it for the coffee table, it is a shame that the potential of such a well-curated selection of images has not been fully exploited.

The significance that such a book was written in Australia should not go unemphasised. Canny’s music has had a global impact, its sounds being repurposed to suit local tastes and needs by musicians a world away in geography and culture. At the same time, it draws its listeners back to the landscape and people of East Clare that Canny knew so intimately. I hope that O’Shea’s book encourages new travellers to make these journeys.

Matthew Horsley is an ethnomusicologist and performer specialising in Irish traditional music.