by David Harris

This article first appeared in the latest edition of The Historical Journal of Tipperary. We are grateful to have received permission from David Harris and the Journal to reproduce the article here. You can see more about THJT at https://tipperarystudies.ie/historical-society/

John Long’s journey

On a winter’s day in February, 1842 Patrick and Mary Long (née Leahy) baptised their 5th child, and fourth son, John, in the Cathedral of the Assumption in Thurles, Co Tipperary. Today, a hundred and eighty years later I stand near his grave in the hot, dry semi-desert land of the Australian ‘outback.’ Emigrating to Australia in the 1860s and becoming one of the burgeoning numbers of the Irish diaspora, John, better known as Jack, was part of a heroic effort to develop this new and challenging land, so different in every way from the green fields of Tipperary.

Jack left Ireland in around 1860, arriving in the Western Australian town of Albany, which was, at that time, the primary port for the Western Australian colony. This was a British penal colony centred on the growing settlements of Perth and Fremantle. Albany, 400km south of Perth, was developing into a farming community and Jack found work there. However, as a free settler (not a convict), he saw that there were better opportunities in the settlements in South Australia, which was a free community. He set sail for South Australia in 1865.

South Australia

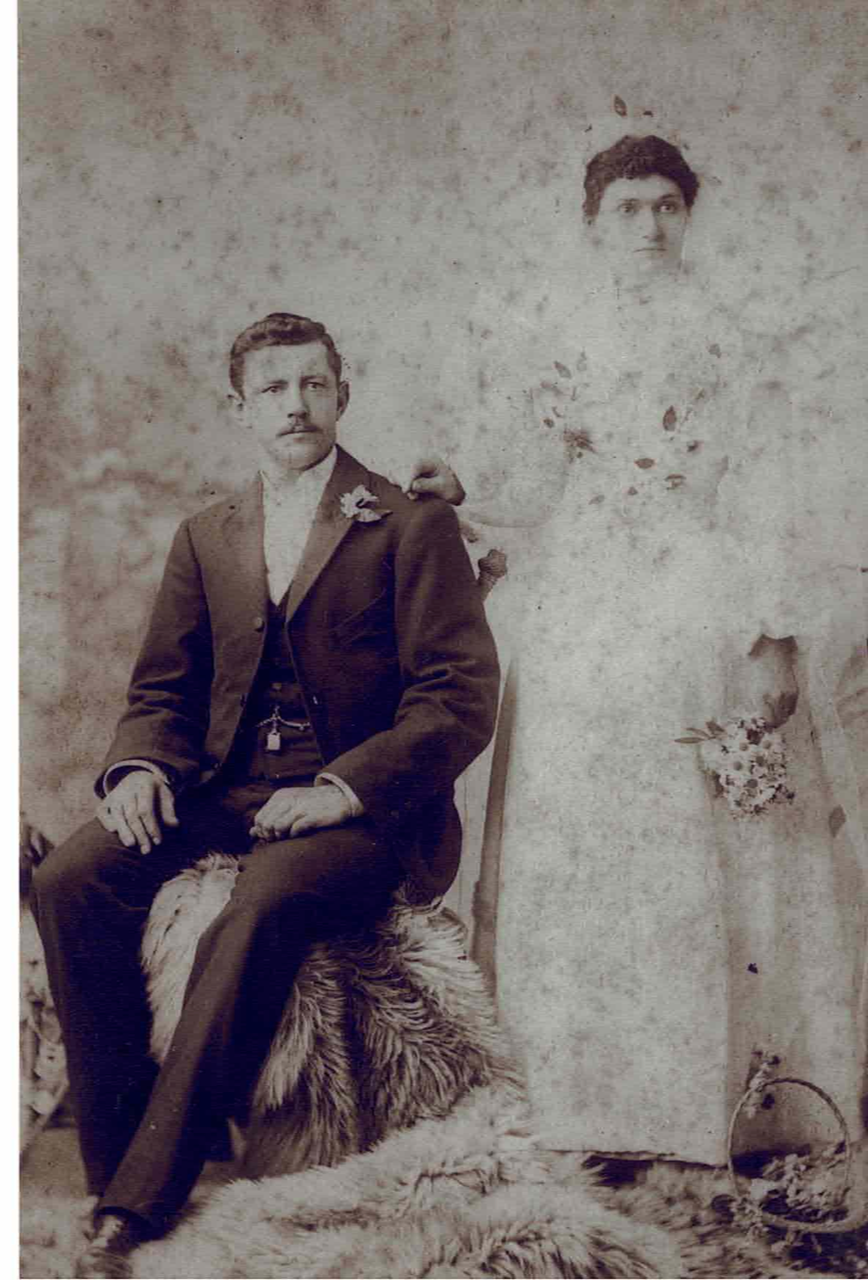

He arrived at the small settlement of Port Augusta in 1865. Within a day or two of arrival he met his wife-to-be, an English woman named Emma Mellowship, and three weeks later, on the 25th December – Christmas Day – 1865 they were married in the nearby settlement of Melrose. They went to work together on a sheep farm in Horrocks Pass, in the Flinders Ranges. Their marriage certificate lists his trade as butcher and hers as cook. We surmise from this that they would have run the kitchen on the farm. They also had their first four children at this time. They were Thomas (1867), Catherine (1868), John (1870) and Amelia (1872).

The environment on his arrival

As the most northerly port in South Australia, Port Augusta became a gateway to the potential farmlands of the inland. With a few years of good rain in the 1870s, it showed potential as a wheat bowl for the colony – so much so that one of the embryonic towns was named Farina – which is also the birthplace of my grandmother. Over a few years, fortunes were made in growing wheat. But then the land reverted to its normal pattern of years of drought, interspersed with occasion good years with rain.

This should have been no surprise. After inspecting northern pastoral lands devastated by a drought in 1864–65, Surveyor-General George Woodroffe Goyder advised the colonial government to discourage farmers from planting crops to the north of a rainfall line which he produced – Goyder’s Line. However, ignoring this advice, the government opened new grain-growing lands stretching for many miles north.

The life of the pioneer settler was one of hardship. Having severed the roots from their homeland, they devoted their lives to clearing the ground – physically and metaphorically – for their children. So they needed to be determined, self-reliant, resilient, and optimistic with a strong belief in their own capabilities. In establishing themselves in the unknown there is no room for hesitancy or caution. So Goyder’s prudent advice was first ridiculed, then ignored as more and more land was cleared, ploughed and sown. They waited for the rain, confident in their belief that ‘the rain follows the plough.’

In considering Jack Long’s experiences in the opening up of this area, one needs to recall that people arrived with skills developed in their lives to date in a European environment which could hardly be more different. So different that most the skills they brought with them turned out to be irrelevant, useless, and sometimes damaging. Clearing land, ploughing, and planting seed worked when rain arrived. When the good years were followed by years of drought the area became a dust bowl. Topsoil (already much thinner than in Europe) blew away. Horses were of limited use. They required feed, which did not grow in this climate. Until the arrival of horses Australia had no animals with hard hooves, and horses found the terrain difficult, and damaged the topsoil in the process. The loads which they could cart were severely restricted by the need to carry feed. Bullock carts were used initially, but their wheels could not survive over ground which was uneven and soft. Simply working in a climate which was so much hotter and drier than Europe, with a burning sun, presented unexpected challenges.

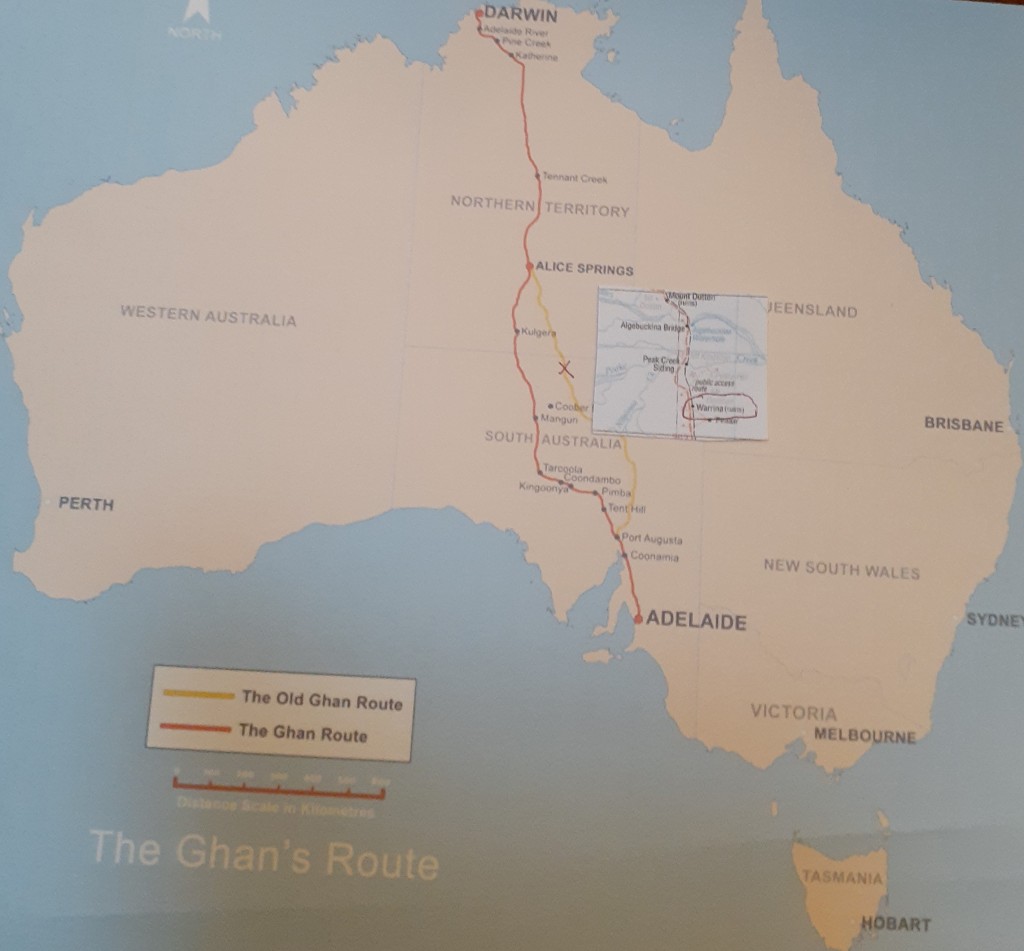

However, to provide faster travel for goods and people, and encouraged by the early, successful days of farming, the decision was made to build a railway north from Port Augusta. In a touch of irony, camels were used to transport construction materials for the railway.

Jack Long and his wife, with their four children, joined the construction teams for this project. Jack and Emma operated the living and catering facilities for the workers on the railway construction.

It is difficult to exaggerate the significance of this project. At 700 km it was a long railway. It was built over country which had barely been explored, and those explorers who had been there were unimpressed by the country. Edward John Eyre, searching for the hoped-for inland sea, climbed a small hill to see the land ahead. He named the hill ‘Mount Hopeless.’ He found no inland sea, but gave his name to the immense salt lake, Lake Eyre, where he had hoped the sea would be. Given the reports of the explorers and the findings of Goyder it is difficult to see how there could have been sufficient belief in the farming potential to justify the railway. Again, it was the character of the settlers, and their reliance on their experience from their home countries which buoyed up their hopes and those of investors in infrastructure projects.

There were significant difficulties in building the line itself. The country was wild, dry and hot, but there were occasional downpours when dry watercourses would be filled with water, flooding the surrounding country and damaging the railway. It was necessary to choose a route linking the infrequent sources of permanent water – occasional springs – as large quantities were needed by the steam trains. They also needed wood, which was not plentiful, and had to be carried on the trains. Add to this that the southern parts of the line wended their way through the rough Flinders Ranges. A tiny part of this line which passes through the Pitchi Ritchi Pass to the town of Quorn is still in service as a tourist experience, run by volunteers.

During their time with the construction of the railway the Long family added a further five children – George (1873), William (1875), Ellen (1880), Emma (1883) and Mary (1886). Then, on the 12th February, 1890, near the small railway settlement of Warrina, tragedy struck. Jack Long was killed in an accident, when he was run over by one of the construction trains. There was a police investigation, which returned a result of accidental death. In this investigation, John’s occupation was given as ‘boarding house keeper.’ The police listed the place of the fatal accident as Warrina. The report also listed his place of burial as ‘unknown.’

Warrina

The construction of the railway continued, reaching its terminus at Oodnadatta in 1891. By this time, the impossibility of wheat farming in this region had been recognised. There was still demand for a rail service in supporting scattered settlements of pastoralists and miners, and in replacing the camel trains. In its final years it also served as a provider of employment during tough times in the development of the colony.

The path taken by the railway was dictated by water availability for the steam trains. Water was available in rather infrequent springs, somewhat like oases, although the indigenous people did not settle at them. Where a significant spring was on the track, rail infrastructure was built – sidings, workshops, accommodation, water storage tanks. Warrina was such a settlement. As the railway was being built the first facilities were for the construction crews. Later, during operation of the railway, they were expanded with water tanks and workshops until, at its prime, Warrina had a population estimated at around 250 people.

With the failure of the wheat-growing dream, it was realised that the country, poor as it was, could support cattle, at a very low stocking rate – about 1 cow per square kilometre. Of course, to run a profitable size herd at this stocking rate, the farms (locally called ‘stations’) needed to be vast, and indeed they are. The largest, Anna Creek, covers an area of around 15,700 square kilometres, larger than Northern Ireland. Warrina is within the boundary of Anna Creek station. However, the operation of the railway was always precarious, and when coal was discovered a new standard gauge line was built from Port Augusta to the coal fields at Leigh Creek, supplying coal to the large power station at Port Augusta. As these trains now had diesel-fuelled locomotives they were no longer bound to availability of water, so the new line bypassed many previous stops, including Warrina.

The settlement of Warrina was abandoned, and today there is hardly a trace of it remaining. The environment in which it was built is essentially sand, with occasional areas covered with small pebbles, but no large stones suitable for building. So, when buildings were put up on the surrounding cattle stations, the remains at Warrina, and similar abandoned settlements, became a quarry for building stone. Today we see only the siding mound and the ruin of an old fettler’s cottage – just one chimney and a few metres of wall to mark the settlement. And there remains the cemetery.

Is Jack Long buried here?

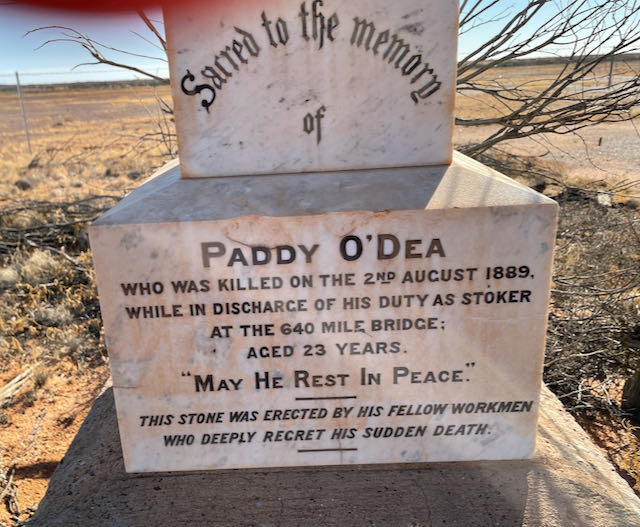

There is a small, but unknown, number of graves in the cemetery – possibly a dozen or so – but all trace has been lost of the people buried there. Although the present land-holders have built a fence around it, it had been unfenced for over 100 years, and the passing animals, domestic and wild, have obliterated any sign of graves which were not protected. The simplest graves had wooden surrounds, which were quickly demolished by termites. The only graves which survived are three which had headstones and surrounding iron fences, intended to prevent the possibility of being dug up by wild dogs. One of these surviving grave markers has a marble headstone with a clear inscription to one Paddy O’Dea. This has been very helpful in locating John’s likely resting place.

Two Irishmen working on the railway construction, at the same time, in the same place, killed a few months apart. They would certainly have known one another. Our belief is that, if Paddy is buried here, it is very likely that John is too.

to be continued next month

David Harris was born in Perth, Western Australia, in 1937, the son of Cliff and Rae Harris (McPherson). Rae was the daughter of Jack and Emma Long’s eighth child, also named Emma (McPherson). David is a retired mechanical engineer, now living in Adelaide, South Australia. He has two sons, Matthew and Chris. Matthew has no children. Chris has four children, all boys, and three grandchildren so far. David is devoting a large part of his retirement to researching his Irish roots, including studying the Irish language.