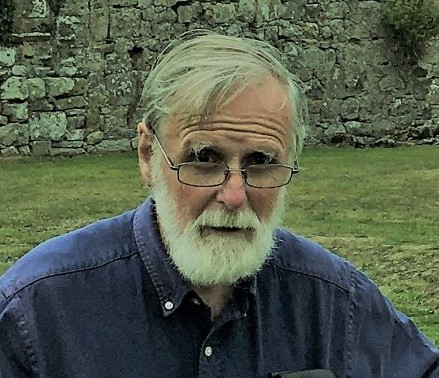

Professor James Lydon

By Robin Frame

James Francis Michael Lydon (1928‒2013) ‒ always ‘Jim’ to his friends ‒ was the most influential historian of later medieval Ireland of his time. He was the author of scholarly and readable books such as The Lordship of Ireland in the Middle Ages (1972) and The making of Ireland, from ancient times to the present (1998). He edited several essay-collections, among which The English in medieval Ireland (1984) stands out, not least for his own contribution on the (Anglo-Irish) ‘middle nation’. His many articles and essays were fluent and accessible, however technical their subject-matter. Lydon was also a stimulating teacher and supervisor, briefly at University College Galway, and then from 1959 onwards at Trinity College Dublin, where between 1980 and 1993 he held the Lecky chair of History. Many of his pupils found employment in university history departments or in archival posts in Ireland, Britain and beyond. In retirement, Lydon kept rooms in college. There, in the intimacy of a small antechamber containing a washbasin and items of outdoor clothing, were shelved copies of dozens of theses ‒ undergraduate as well as postgraduate ‒ he had overseen down the decades. To those who helped to sort his papers after his death, these were a poignant reminder of how much his teaching meant to him, and to them.

James Lydon was born and educated in Galway city, where his family owned a bakery. After he graduated at UCG in 1950, with first-class honours in English and History, and began research for an MA by thesis, his professor, Mary Donovan O’Sullivan, encouraged him to spread his wings. He pursued his doctoral studies at the Institute of Historical Research in London. Two distinguished medievalists spotted his talents. He was supervised by J.G. (later Sir Goronwy) Edwards, historian of Wales and of the English parliament. Sir Maurice Powicke, recently Regius Professor of History at Oxford and decades earlier professor at Queen’s University Belfast, also took an interest in his career. Powicke advised him to use a National University of Ireland travelling scholarship to visit Rome, to advance his cultural education. Later, he urged UCG to find a job for him. After three years back at Galway, Lydon applied, again at the urging of Mrs O’Sullivan, for a junior lectureship at TCD. While Catholic students were not a rarity at Trinity, the restrictions (known as ‘the ban’) imposed by the archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, deterred many. Students were chiefly drawn from the Protestant communities north and south of the border, and from grammar and public schools in Britain. Lydon flourished in this new environment; he became a staunch defender of Trinity and its ethos and a vocal critic of the ban, publicly in an appearance on the Late Late Show on Irish television in 1967. He was particularly distressed by McQuaid’s refusal to appoint a chaplain for Catholic students and staff.

Lydon and his predecessor in the Lecky chair, Jocelyn Otway-Ruthven, were an unlikely pairing. ‘The Ot’, who came from an Anglo-Irish gentry background, was a pillar of the Church of Ireland; Lydon belonged to a large Catholic family, with an Irish-speaking mother. As historians, they were temperamentally far apart. She was an exponent of a somewhat abstract history of institutions, which she did not sweeten with any liveliness of prose style. His approach was more instinctive, and he did not disdain the sweeping argument or the vivid phrase. Yet in general they got on. She loyally forwarded his career in college, while he appreciated her austere scholarship and caustic wit, and came to understand the shyness and awkward kindness that lay behind her forbidding persona. They were of one mind in deploring the antique dispensation that until 1968 denied women election to Fellowship and full common room rights.

Lydon was an engaging lecturer with, even in late middle age, a boyish charm. In first-year lectures he held students from England, many of whom knew little or nothing about Ireland, spellbound as he explored the mysterious origins of the Irish people and the controversies that raged over the date and character of the Patrician mission. As a tutor he was no pushover: woe betide those who submitted slipshod work or produced pompous waffle that suggested a lack of serious engagement with the subject. But he had to an unusual degree the gift of bestowing praise and kindling enthusiasm. I was one of the many who benefited. History had been my favourite subject since childhood, but in public exams I had scored much better marks in English Literature and Latin. An early encounter with Lydon, when he heaped praise on my first essay, was crucial in dispelling my uncertainties and instilling confidence. (Possibly his good opinion owed something to the relief of coming across a typed essay, a rarity in those days, amidst a heap of scribbled offerings.) Similar characteristics marked his postgraduate supervision. Inconsistencies in footnoting would be mercilessly pounced upon, but a small discovery in the archives would be hailed as ‘a nugget’ and the germ of an idea as ‘an eye-opener’. Bureaucratic measurement of ‘completion rates’ lay far in the future, but those he achieved were excellent, partly because he demanded written reports and drafts of chapters, however half-baked, from an early stage. He understood that the act of writing clarified thought and guided further research.

Lydon’s publications fall into two categories. For his PhD he had studied Ireland’s contribution of manpower, cash and supplies to the military activities of Plantagenet kings in France, Wales and Scotland between 1199 and 1327. This involved combing the unpublished evidence on both sides of the Irish Sea, in particular tracking down the neglected transcripts and calendars of the records of the Dublin government that had survived the destruction of the originals in the Public Record Office in Dublin in 1922, during the civil war. This research led to substantial articles on Irish armies, the Irish revenues, taxation and consent, and parliamentary history. In 1965, a conference paper he had given on the Irish parliament was published in The English Historical Review. This was the first article on the medieval lordship of Ireland to appear in that august journal for many years. It foreshadowed one important result of Lydon’s work and that of his pupils: the reconnection of the history of ‘English’ Ireland with that of England itself.

Lydon never lost his interest in these matters: one of his last pieces of writing, published in 2009, was a study of the alleged financial shenanigans of the Irish treasurer, Alexander Bicknor, archbishop of Dublin from 1317 to 1349. But college duties and a shift in his own priorities diverted him from bigger projects in governmental history and its sources. There was also a mishap reminiscent of T.E. Lawrence, who lost the manuscript of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom at Reading station in 1919, when the only typescript of Lydon’s edition of what could be salvaged of the lost Irish exchequer Pipe Rolls of Henry III vanished for ever when he moved rooms in college. This side of his work, too, has been carried on by those he taught, who have in turn enlisted a further generation. The Irish government records that Lydon had chased through a dozen or more repositories are now available in printed or online editions. The magnificent website ‘Beyond 2022: Ireland’s Virtual Record Treasury’ (https://virtualtreasury.ie) is an indirect testimony to his influence.

From the late 1960s Lydon became preoccupied with broader treatments of Irish history. He was one of the two general editors of the Gill History of Ireland (1971‒75), which included good short studies of the medieval period by Donnchadh Ó Corráin, John Watt, Kenneth Nicholls and Lydon himself. At the same time, he was working on his own, longer book, The lordship of Ireland, where much of his thinking crystallized.

These new ventures coincided with alterations in the pattern of his existence. He acquired a house ‘up a mountain somewhere in Wicklow’ (as he put it). Later, he had a less isolated dwelling in the village of Hollywood, where he became part of the local community, attending Mass regularly, propping up the bar, and in earlier days helping with the harvest. He also began to suffer from a form of arthritis that reduced his zest for travel and for days sitting cramped in the archives. Alongside his warmth and affability there was a need for withdrawal, which could trouble his friends. ‘Jim said he might come’ was a phrase often on the lips of those who looked around for him, sometimes fruitlessly, at social gatherings in Dublin.

In a poem written to preface a Festschrift presented to Lydon in 1995, Brendan Kennelly described History as, for him, ‘a passionate art’. He was certainly passionate about Ireland’s past. He also saw the historian’s work as an individual, imaginative pursuit. The preface to The making of Ireland ends with the sentence ‘each person, in each generation, must discover the past’. I once rang him from Durham to moan about my inability to get on with things. He replied, ‘don’t worry, it will come back’. I wondered afterwards what ‘it’ was. I suspect he meant Clio, the Muse of History. The hills and glens of Wicklow nourished his deep, romantic attachment to his country and its people. His interests inclined towards literature and music rather than towards the social sciences. He had a large and valuable library of Irish literature, with an emphasis on the Irish literary revival. J.M. Synge, perhaps because of his Wicklow roots, was a favourite.

Though Lydon’s historical reading was wide, in print he rarely discussed the views of other scholars. He had limited patience with debates about techniques and interpretations, and even less with ‘theory’. These belonged off stage; they should not get in the way of what he valued most: direct engagement between the historian and the primary sources, and between the historian and the reader. He knew that his approach laid him open to criticism. Brendan Bradshaw acted as publisher’s reader for The making of Ireland, the book that occupied his early post-retirement years. Lydon told me that while Bradshaw’s report was generally positive, it suggested that the book would benefit from wider contexts and a more comparative approach. ‘He’s right, of course’, Lydon said a little plaintively, ‘but I don’t do that’. His focus was always on what he perceived as Ireland’s interests. A reviewer of The lordship of Ireland questioned the ‘air of reproof’ that frequently marks his accounts of crown policy, which he saw as a malign mixture of neglect and exploitation. This finger-wagging might, perhaps, have been tempered by more explicit consideration of the nature of pre-modern dynastic empires or ‘multiple kingdoms’, and the outlook of their rulers. While he was not hostile to the ‘British Isles’ history that became fashionable in the 1980s and 1990s, he saw it chiefly as an opportunity to make medieval Ireland better known in the outside world. Just as he had reservations about Ireland’s entry into the EEC in 1973, he was not keen on Irish history being levered into some other intellectual construct.

At times Lydon may have painted with too broad a brush for some tastes; he was not one for splitting hairs (as he might have seen it) or dwelling on ambiguities. But this was the flip side of his strengths as a historian, which included emotional engagement with the subject, power and clarity of argument, and the ability to bring the past to life for readers through telling examples from literary and annalistic sources as well as the government records on which he had cut his teeth. His achievement was to revive the study of a neglected stretch of the Irish past both through his own writings and through the fascination and lasting commitment he inspired in those he taught.

Robin Frame is professor emeritus of History at the University of Durham. He studied at Trinity College Dublin between 1962 and 1969. He knew Jim Lydon for more than fifty years, as a tutor, a doctoral supervisor, and above all as a friend. His latest book, Plantagenet Ireland, was published by Four Courts Press in 2022.

Photo courtesy of Robin’s family.

Trevor McClaughlin is a member of the Tinteán editorial team.