A Feature Documentary Film Review by Marie Meggitt

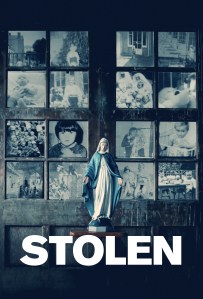

Stolen, Directed by Margo Harkin, a Besom/Wildfire co-production, 2023.

Stolen is a horror story of the treatment of women in a society so deeply misogynistic, that no level of brutality was unacceptable, including the mass murder of our children. These children’s deaths were presumably justified because it ensured that the offspring of we ‘fallen women’ would not go on to infest the society by their very existence. This documentary tells the story of women and children imprisoned in the mother and baby homes that were built and managed by the combination of church and state in Ireland in the 20th century. It is a true story, and the purity of that truth is given strength because it is told in the first person by some of the many victim-survivors of these chambers of horror. There is no ‘actor’ required. The voice of lived experience brings a power more authentic and raw, and the audience cannot unhear the pain and the grief.

To call it a documentary is to undersell its power however, as there is not a moment when the audience can look away, zone out of the listening, let go of the feeling of shock, disbelief and grief at what is being revealed. It is exquisitely crafted through the many elements of film making. The music, and the intentional silences are thoughtfully chosen. The juxtaposition of quiet lyrical poetry, delivered in that beautiful Irish lilt, screams the rage of what has been done to us in the name of God and the Church. Reconstructions are used cautiously, never overdone, as is black and white film dating back to the 50s and 60s. Film of these imposing gothic buildings, now derelict, emphasise the dereliction of duty, compassion and humanity that is the story of this ugly, vicious expunging of the lives of thousands of babies and children and the trail of grief, loss and paralysing secrecy that dominated the lives of those who survived and their mothers.

I am not a neutral viewer: I am a mother whose child was taken during the forced adoption era in Australia, and as in Ireland, Australia had its mother and baby homes. I have been an activist for change for over forty years now and still I found STOLEN deeply unsettling. It is a hugely important contribution to revealing the truth in the trade of babies that is still occurring today in the 21st century and in several different forms now. Adoptions are rife, but more so in other countries, particularly America. But the modern version of women being exploited for their children is surrogacy, and we can find ‘homes’ in many countries that now hold 30 or more impoverished women who are pregnant. These women are not allowed to leave the ‘homes’ (even though many have other children to care for in their own homes) until the baby is born and handed over to the commissioning couple. Except of course, where the baby has some abnormality and then the mother is required to take it home, let it die, or put it in an orphanage. Some of you may remember the Baby Gammy case in Western Australia. Look it up if you don’t.

Stolen provides us with a history lesson that is not yet in the past. There are still many of our children taken for adoption who are fighting the veil of secrecy that had been drawn over these illegal and inhumane practices. Mothers also struggle to get records. Many records have been corrupted by lies, burnt, ‘lost’, thrown out and forged. STOLEN tell of a litany of illegal practices – kidnapping, trickery, selling babies, sending babies overseas, imprisoning girls and women for long after the birth of their children to ‘pay back’ the home and significant debts being created for families who had the tenacity and temerity to bring their child home.

A recurring theme in the film is the need for the truth to be known. This is as simple and profound as ‘who am I’, ‘where do I come’ from’, ‘who is my mother’. It is powerfully conveyed in the film through the line in the poem ‘I look like no-one’. To have to ask these questions, to not just know the answers, is such a fundamental breach of humanity. And so is taking our children and ensuring that we will never know them, imposing the blanket of secrecy so completely that as we grow up (so many of us were just young teenagers) and grow old, we don’t know whether they are alive or dead, returned to the State, abused or feted in their new homes.

In Ireland, what we know now is that in one of these institutions, in the first seven years it was open, 4025 babies were born and 3200 of them died. This was no accident. This was a system approach, an attitude to mothers and our babies that reflected the deepest misogyny. This is but one statistic from the many homes that were established in Ireland, the last of which closed in 1998. The Bessborough Mother and Baby Home in Cork, by 1934, had the highest recorded infant mortality rate among all of Ireland’s mother and baby homes. It was reported in the BBC that during 1943, three out of every four children born in Bessborough died – a mortality rate of 75%. as reported by the BBC. Incredibly, the authorities whose role it was to investigate homes gave them clean bills of health, even commenting on how well-fed the babies and children were. This was in the face of the starvation and death of hundreds of them.

It is a damning indictment on the Irish government that the Commission set up to investigate these homes brought down their Report in 2022 and found no evidence of forced adoptions. Not only is the evidence overwhelming but the Commission was set up in such a way as to ensure this outcome. Watch the film to see how this was achieved. In Australia, all state governments and the Federal government have acknowledged and apologised for the Forced Adoption era. In Victoria, the first in the world to enact a Redress Scheme for mothers who had their babies during these years, has been implemented.

Stolen is one more step towards justice for mothers and their babies and it is an unfinished story. The vital place of truth and the damage done to people by lies and secrecy is redolent, as is the institutionalised hatred of women, and the willingness of men in the Church in particular, to punish us. I think it is best summed up by Enda Kenny in his speech to the Irish Parliament – ‘It is not just a burial ground; it is a social and cultural sepulchre. We did not just hide away the bodies of tiny human beings, we dug deep and deeper still, to bury our compassion, to bury our mercy, to bury our humanity itself.’ It is not only the deaths of our babies, it is the lifelong grief and shame and loss, the lies, the secrecy, the overwhelming unwillingness of the perpetrators to acknowledge the damage these have wrought on the lives of so many women and children, that is the lasting impact of this jewel – STOLEN.

Marie Meggitt

Marie is the founder of ARMS, the Association Representing Mothers Separated by adoption. This group achieved a change in legislation in 1984 that gave adopted people the right to know their family of origin. The Victorian Parliament’s lead ensured that all states in Australia provided this same right to adopted people. Subsequently, ARMS lobbied strongly for the same rights to be afforded to mothers. The redress scheme was implemented in 2023 in Victoria and is currently taking applications from mothers whose children were taken during the forced adoption era. ARMS has led this initiative world-wide.

Something is wrong with the System

Lie of the Land (2023), Directed by John Cardin, starring Nigel O’Neil, Ali White and John Kinsella. Written by Tara Hegarty with cinematography by Jennifer Atcheson.

A Feature Film Review by Dan Boyle

I grew up listening to horror stories of unfortunate people who had been evicted, put out on the street or who had done a bunk, a moonlight flit. They seemed good people who had fallen on hard times. I felt their shame. Nevertheless, they must have been, at least, partly to blame for their predicament. But when this happens wholesale to farming families, something is clearly wrong with the system. For this film set in Ballymena, Northern Ireland, we can blame the British. Nice one Boris Johnson!

The expression ‘Lie of the Land’ means how things are or have become and perhaps, the lie that a rural life would always have been sustainable. Childless farm couple Matthew and Kath Ward have become a rural tragedy. Up to their necks in debt. No assets but their farm mortgaged to the bank. No way out. Matthew, dourly played by Nigel O’Neill and Kath, his resolute farmwife, Ali White, clutch at a too-good-to-be-true straw, in the form of angel-faced Gabriel Shepard who turns out to be far from the good. Gabriel offers to help the Wards disappear overseas with whatever money they can scrape together by selling off their herd. So far, so desperate.

This is a wonderful setup for a social drama. Screenplay, Tara Hegerty, from her radio play ‘The Crossing’. Double-crossing takes the conventional turn, however, into a suspense chiller, along the lines of Sam Peckinpah’s ‘Straw Dogs’. Nigel O’Neill who must be Sam Neill’s long-suffering Irish cousin impresses as Matthew Ward. Ali White discovers a new depth of womanly fortitude as Kath. Barry John Kinsella (sounds like his rap sheet!) presents his acting palette from sweet-faced carpet bagger to force-of-nature hard man.

What choices ensure a film’s success? Make it as a suspense chiller or go for social drama with a message? The filmmakers have made their choice, as will the filmgoers. In conclusion, a well-acted and directed film that missed the opportunity to be greater.

Dan Boyle

Daniel Boyle is a Melbourne actor/performer/ director who has done everything from Shakespeare to the Broadway musical