A Book Review by Frances Devlin-Glass

Rodney Sullivan and Robin Sullivan: A Hundred Thousand Welcomes: The History of the Queensland Irish Association, Boolarong Press, Brisbane, 2023.

ISBN: 9781922643520

RRP: $39.95

As one who grew up in Brisbane in a Catholic bubble (which, astonishingly, was rarely breached until the end of my undergraduate life in the late 1960s), I was keen to read this history of the Irish cultural life in my city. My day-to-day life was replete with Irish nuns and priests, sodalities and rituals like the massive Corpus Christi processions that happened at the Exhibition Grounds annually, and I had a short term as an Irish and Scottish dancer (my mother couldn’t afford the Scottish socks, much less other regalia, which was simpler than it is today). And yet, until I’d left the city as an adult, I was unaware of the existence of the Queensland Irish Association. This book made me wonder why and whether or not my father, Hibernian Sodality member and a club-man, ever set foot in it. A brother, who is a barrister, certainly did, because that’s the kind of club it was, but he was never a member.

The Queensland Irish Association (QIA) was indeed, in Rod and Robin Sullivan’s superbly-documented account of it (drawn from personal archives and photos and memorabilia of memories and oral and professional histories), a major institution in the city. It invites comparison with Melbourne’s Celtic Club of which I’ve been a member for over 20 years, but in this review I’ll diligently eschew comparisons, and focus instead on what the QIA offered members and on this remarkable history of it. This is a commissioned history by proud members who are professional academic historians, and although there are supplementary questions one would like to ask, and perhaps some air-brushing of the difficult bits of the history, one has to admire the richness of the sources they have at their fingertips and the adroit ways in which they map developments over the QIA’s long history onto Irish and Irish-Australian historical developments.

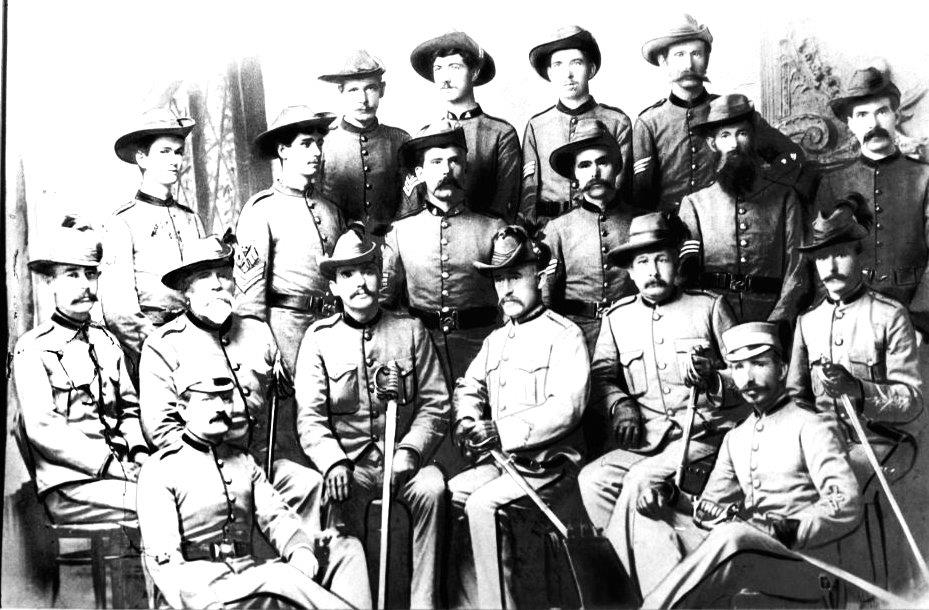

Founded in March 1898, the QIA built on the work of the Catholic Bishop James Quinn who had responded to the Great Famine by making inducements to survivors to settle in Queensland. The first contingent was transported in a ship called Erin go Bragh in 1862. The QIA incorporated the remnants of two earlier organisations – the Queensland Irish Volunteers and the Queensland Hibernian Society. The former (led by Irish parlimentarians) had a defensive military focus on protecting Queensland and recruited from the Scots and Irish, and all denominations (they were inclusive), though their loyalty was often questioned by their British overlords. There’s a fascinating photo of a group of them on p.11, looking like a group off to fight the Boers with slouch hats and ceremonial (potentially combat?) swords prominently on display, but they did not see service. They were forced out of uniform after the St. Patrick’s Day procession in 1897, and regrouped under the banner of the QIA. The Queensland Hibernian Society was founded by the redoubtable Kevin O’Doherty – convicted and transported to Tasmania for his role in the 1848 rebellion, a graduate of the Royal College of Surgeons (Dublin) and admired medic, and an elected representative to the Queensland Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council. He and his wife Mary Eva Kelly, ‘Eva of the Nation’, a poet, were to become perhaps the most prominent and cherished of the Queensland Irish.

Already in the days of its establishment, the QIA was keen not to replicate the sectarianism they’d left in Ireland and to be inclusive. Most of all, in the face of rabid sectarianism, they intended to be respectable, aspirational, upwardly mobile. A persistent theme in this history is how very upper-crust the QIA was, how non-sectarian, how well-connected to the big end of town – to Lord Mayors, parliamentarians, bishops and archbishops (of different flavours), and the legal and medical fraternities – and how very upwardly mobile its members were. The date of the QIA’s foundation marked the centenary of the United Irishmen’s rebellion in 1798, and its inclusiveness of all denominations gave impetus in the QIA’s modus operandi to the conviction that nationality should override religious affiliations. The Sullivans, however, point to the telling detail that Protestants failed to support the centenary celebrations in 1898, and comment that Protestant versions of history were often at odds with Catholic ones. Nonetheless, it seems not to have unduly threatened cohesiveness. Another thread of cohesion was the unquestioned assumption that piety to Ireland should not occlude a primary commitment to Australia, the new homeland. Tensions between these affiliations, the writers point out, would from time to time simmer, especially in periods when the QIA was run by native-born descendants of Irish (during the Depression) when the club became more Catholic in tenor than Irish and had to struggle to define itself as Irish. Its inclusiveness, however, made it the stand-out Club in 1908 in a city sporting seven such clubs.

The story of Frank McDonnell (1862-1928), draper and politician, is emblematic of their ambition. Educated by the Christian Brothers in Ennis, he lost his father at age 7 and was apprenticed as a draper in Ballina (Mayo) aged 13, alongside another Irishman, T.C. Beirne, who would also migrate to Brisbane and also build another major Emporium in Fortitude Valley. McDonnell built his capital on a farm as a rural labourer on the Darling Downs and founded another of the large emporia in Queensland, in George Street (not too far from the Roma Street Railway mecca). He employed my grandfather when he first migrated after the Easter Rising (his family had drapery, high-class millinery and dressmaking and jewelry-making interests in an emporium on Patrick St, Cork). McDonnell was to become an important supporter of education in the state, a social justice activist and philanthropist in Queensland and in Ireland.

The QIA was eager to support delegations from Ireland and continued to do so into the twentieth century with receptions for Presidents Patrick Hillery (1985), Mary Robinson (1993), Mary McAleese (1998) and Michael Higgins (2017). Beginning with the visits of Redmond (Irish Parliamentary Party – IPP) and later Joseph and John Donovan in 1911-12, the QIA gave impetus to enthusiasm for Home Rule in the decade before WWI. Redmond commented on how successful QIA members were in Australia and made comparisons with counterparts in Ireland who ‘would have had difficulty avoiding prison’ or ‘qualifying for jury service’. There may have been a touch of flattery in such descriptions, as Redmond was fundraising for Ireland, but certainly the QIA’s membership saw a stellar rise over the next century and a bit. In 1925, the delegations of two Republican women, Linda Kearns and Kathleen Barry, would continue the tradition of fundraising in the diaspora, collecting for victims of the Rising and the anti-partition cause, and managed not to be expelled from Queensland (unlike earlier delegations).

The Sullivans contest Patrick O’Farrell’s notion that the Club was ‘past-directed’ and nostalgia-driven and point instead to the keen interest taken at the QIA in contemporary Irish affairs, especially Home Rule. The QIA’s response to the Rising was initially hostile, not surprisingly as a Queensland Government delegation, led by Premier T J Ryan, was in London soon after the Rising and socialising with the IPP and with a depressed Redmond and his followers, and being told ‘that the Kaiser was the real author of the rising’. All were alarmed at the impact on Home Rule, and at home, there was legitimate concern about the impact on Australian Irish troops in battle zones. Younger members of QIA had enlisted in the Australian army; 134 who were serving in Europe were kept on the membership roll of the club free of charge.

Although there were some who would vehemently support the Rising back in Brisbane (they would eventually be given Life Memberships in the QIA after being initially expelled for their views), in 1916, they were in the minority. QIA members were at the centre of a political firestorm and ‘tarred with the disloyalty brush’. T C Beirne (emporium owner mentioned above) successfully prosecuted a Protestant weekly for discrimination as a Catholic when it accused him of undermining the war effort. Although he had not been named, details identified him, and record damages had to be paid. An acrimonious split within the QIA resulted in a splinter group, the Irish National Association of Queensland (INAQ) which supported the Rising, Sinn Féin, and republicanism. Later during the 1920s, INAQ brought controversial delegates from Ireland (some of whom were deported from New South Wales) to fundraise for the Republican cause and the families of victims of the Rising. Another and even more significant split occurred after the Rising in the Labor Party in Queensland.

What emerges from the Sullivans’ history for me is how very multi-stranded the social activities in the QIA were – all manner of educational and recreational activities from literary and debating circles, a library that became a literary hub (attracting as guests and speakers both locals as well as luminaries like Maeve Binchy, Thomas Kenneally, Seamus Heaney and Frank and Malachy McCourt), pipe bands, a choir, dancing classes and competitions, St Patrick’s Day parades (a public holiday, ‘sacred to Irishmen’, in Brisbane after 1903), Irish sports, annual dinners for men and women (in gendered groups until quite late in the history of the Club much to the dismay of feminists). What made this possible was that from 1919, it had its own clubhouse, and it was continuously expanded, so that dinners could seat up to 900 people, a scale of operation that was undoubtedly unrivalled by any other Irish club in Australia.

One of the most intriguing aspects of this historical treatment is the account in the substantial chapter, ‘Women: From Outside to Inside’, that precedes the conclusion (suggesting its importance to the authors) of the Club belatedly bringing women into its orbit. They had been energetically doing the work for the signature balls behind the scenes, but excluded, shamefully, from men-only St Patrick’s Eve dinners, the highlight of the social life of the club. The historians’ moral stance is bluntly headlined by the comment early in the first paragraph that ‘Masculinity pervaded its culture.’ And further, that it was ‘not perceived as unjust discrimination’. It had foregrounded men’s sports, celebrated male Irish literary and legendary heroes (including their local heroine and poet, ‘Eva of the Nation’ from consideration), and ‘on occasion, indulged in patriotic Irish militarism’ (p.235). Although they featured Linda Kearns in 1925, it was shamefully not by name, and Delia Murphy, a singer with a global reputation, was similarly occluded by being referred to as the wife of the ambassador. The club slowly responded to a more feminist zeitgeist, and by the 1980s was still ambivalent when in 1981, Michelle Grattan, and Anne Summers, senior political journalists, sought to attend when Malcolm Fraser was guest speaker at the St Patrick’s Eve Dinner and were refused. The Human Rights Commission got involved, and membership law changes were made, making it possible for women to become full members. An even more embarrassing occasion was when Brisbane’s first female Lord Mayor Sallyanne Atkinson was, as the custom dictated, invited to sit at High Table but ‘only as Lord Mayor and not as a woman’. It took a phalanx of feminists (led by a friend and colleague, Northern Irish-born Rebecca Pelan) and protests to overturn the discrimination in the 1980s and ’90s. The spectacularly successful visit of Mary McAleese permanently changed the culture of the club. The result was a resurgence of cultural activities in the 1990s – QIA scholarships rich enough to take students to Irish Studies courses at top UK universities, dinners boasting Irish Dancers and Pipe Bands, Debutante balls, theatre parties to see Irish plays at the Queensland Theatre Company, pipe bands visiting Ireland and Scotland, visits from Irish notables like Conor Cruise O’Brien and Máire Mhac an tSaoi, QIA collaborations with academics on projects, the revival of St Patrick’s Day parades, and much more.

The almost fatal collapse of the club after the brilliant decade of the 1990s was occasioned by many factors: an expensive refurbishment of the clubhouse, the loss of rental income on the ground floor, high levels of debt, and building compliance issues. To compound these difficulties, a major flood of the Brisbane River in 2011 seriously damaged the Tara House basement and its historical records. Membership plummeted from a high of nearly 1000 members in 1996 to 350 in 2011 with a generation less focussed on community involvement and cultural investment, and dealing with more demanding workplaces. Insolvency loomed with a debt of $3.125 m. It is a minor miracle that the club’s fortunes were successfully revived with the sale of Tara House in 2016 (the club retained just one floor of the building thus alleviating building maintenance costs significantly), more conservative financial management and a return to the wide variety of cultural activities which had always been the mainstay of the club in its vibrant periods. Closure was averted, but the trauma was real until 2018, when memberships began to recover. The more confident acknowledgement and deployment of women were part of this metamorphosis.

This is a fascinating history, about a world that, though it was contiguous with mine and my interests, sadly didn’t overlap. It should be compulsory reading for members of Irish clubs wherever they occur.

Frances Devlin-Glass

Frances grew up in Queensland and in an almost exclusively Catholic enclave; her Irish identifications were based in family. She is a member of the Tinteán editorial collective.