A Feature by Jules McCue for St Brigid’s Day (Imbolc, 1 February)

Reflecting on the Third Life of St Brigid ‘Bethu Brigte’ (unknown authorship) and the changing lives of women.

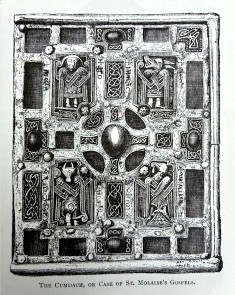

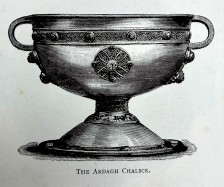

This sketch and subsequent ones are to be found in Irish Pictures: Drawn with Pen and Pencil by Richard Lovett, M.A. The Religious Tract Society, 56 Paternoster Row and 164 Piccadilly, 1888.

In February last year, 2025, Tinteán published my review of the recent publication Two Lives of Brigid, edited and translated by Philip Freeman, concerning Brigid’s life and deeds, one written by Cogitosus in the seventh century, the other of unknown authorship. In this article I include elements from a third life of the saint, Bethu Brigte. It would be difficult to prove which came first and how many other texts have been lost or destroyed, of which there were many due to her significance in Ireland, Europe and the British Isles, whereupon the western Scottish islands, ‘The Hebrides’ and many churches and wells were named in her honour.

Leyla Telli, in her Narrative Analysis of Bethu Brigte, informs us that the discussion of the name ‘Brigid’ can be traced back to Indo-European roots meaning ‘great, sublime’ and was the epithet for a range of pre-Christian goddesses, adding that, ‘The transmission of a few short lines about the goddess Brigit in Sanas Cormaic has fueled this discussion. Since there is no other direct textual mention of the goddess, it is tempting to try to find out more about her through perceived relicts of her cult in the vitae of the saint’. [Telli: 3-4] I previously discussed the syncretic merging of saint and goddess and possibly other aspects of Irish, native tradition merging to create the extraordinary Brigid we sense we know today. Thus, Telli also notes that Brigid performs miracles involving fire, connecting her to former pagan deities and that in all three ‘Lives’, many of her miracles are derivations of Christ’s miracles of the New Testament.

The Bethu Brigte is a quasi-chronological, narrative exposition of the composite figure, expressed through the language of the time, descriptive imagery, explicit cultural customs and the supreme sacredness attributed to the holy virgin. Unlike the other two ‘Lives’, there is more topographical and social detail, so that the structure of the text is not entirely based on a series of magic tricks conveyed to us as miracles. The style is largely Realism, for example, the vivid description of the beer brewing process. The author furnishes us with names of people and places, where churches and monasteries were established, mostly only fragments remaining.

As in the other two ‘Lives’, time, Telli observes, is not specific, regarding hours, days and weeks. Seasons and their produce illuminate yearly events, and holy occasions indicate biographical events in her life, for example, when as an infant she emanates columns of fire and radiating light, or when she received the veil, the day she met St Patrick, and her visit with Bishop Erc to the Dingle Peninsula near Mt Eagle, the home of St Brendan the Navigator years later. In all three ‘Lives’ the miracles contain similarities in order and deed. Each of her pilgrimages across Ireland, has a purpose, especially after her ordination as a bishop, when for example Easter, a venerable liturgical time in the Christian calendar, is given much importance. After all, Easter is in spring and Brigid is associated with renewal of the soul, new life, the harvest and poetry. Tilli points out the use of the Latin words gair iarum or iarum in sections one and three, wherein explicit chronology is lacking. These words denote something like ‘shortly afterwards’.

Telli notes that language is of special significance in the Bethu Brigte, as it is mostly written in the Old Irish vernacular, the remainder in Latin; the latter used to highlight important information pertaining to happenings and Brigid’s insightful words denoting her revered and hallowed life, invested in her by God her master. The language is not as formal as in the other ‘Lives’. Telli writes about ‘Laconic diction versus saintly humility’. Brigid’s speech is often audacious and forthright. When asked if a situation could be remedied, Brigid often answers with the terse ‘not hard’, just two words; perhaps a way of saying ‘easy peasey’ or in Australia ‘not a problem’. Telli sums up – ‘Holiness and greatness is thus expressed through a synthesis of native traditional story-telling patterns that are used as a tool to promote Christian ideals and faith’. (Telli:13)

Telli emphasizes the theme of Brigid’s holiness, the special quality that makes a person a saint. This was sensed and recognized by nearly all who met her from early childhood. After a radical start, she mellows, becoming virtuous, abundantly charismatic, patient, strong of will and character, performing miracles through prayer and spiritual focus. No wonder she accumulates a large following. She is willing to defy her father’s and other chieftains’ authority to achieve the work of God, maintaining an ascetic life of humility and purity. When her father finds a suitable husband for her, she diplomatically found the good man a more appropriate bride. As previously mentioned, the people of mid-fifth century Ireland did not aspire to contain their children in the perceived unnatural state of ‘virginity’ when marriage to acquire wealth and progeny was a necessity to continue inherited social position and power. Therefore, sexual reproduction ensuring the succession of power was to be celebrated and facilitated. This is relevant to the conversion of Ireland, because most of the monks, abbots and nuns came from the ruling classes; they had time, education and power. St Patrick used the wise strategy of enlisting missionaries of status to spread the word of the gospels. After the Cambro-Anglo-Norman invasion, a girl could be beaten for refusing to marry a selected partner. Surely this custom would have precedence in pre and early Christian times? Patrick says in his fifth century Confessio that women’s conditions had become miserable. The logic follows that religious houses improved their lives.

Scholarly evidence from the early Irish law tracts reveals much about women’s roles and status. However, they conclude that the body of knowledge is far from definitive regarding the changing lives of women through the conversion to Christianity. High status men often had many children with ‘other’ women, outside their primary marriage. The Irish words used to describe marital status and roles of women were finely nuanced to enact laws. For example, one word for concubine is adaltrach and denotes a second wife of less status but nonetheless not morally derided, rather accepted as a role in that society. The words meirdrech and adaltrach – were adopted from Latin by Brehon Law but as Tracy Newlands says, had ‘distinctly damning overtones’. (Newlands:434). Meretrix in Latin means prostitute and adaltrach speaks for itself, but in the traditional Irish society, she notes that these words were more ‘descriptive than morally judgmental’. The church attempted to make laws [Canon Law] that would align with early Irish Law to ease the transition. But as we observed, Irish Law also borrowed from Latin, the language of Christianity in western Europe at the time.

Newlands concludes that ‘references which indicate formal recognition of moral decrepitude are overwhelmingly couched in terminology which is borrowed from the Latin culture’ (Newlands:435). Nevertheless, it is perceived that life improved for some women in early Christian times, remembering that pre- and post- Christian frameworks have been perceived from the male viewpoint. Undoubtedly, aspects such as human sacrifice and forms of sex slavery being outlawed, ameliorated their plight. Brigid takes in many young women perhaps to protect them from abuse and unwanted marriages. She empowers them by giving them moral and material support. However, the powerful male clergy gradually determine the way of life for women, and there is significant change in overall positions of morality brought about by the law of chastity particularly for males: monks, abbots, bishops and priests. How was this manifested? The need to control the sexual behavior of women stems from their threat to the patriarchal control of secular society by the church, as by the twelfth century, high kingship was inextricably linked by historic, hereditary connection to the powerful ecclesiastical centres. This system had been controlled by male clergy who married so that their offspring became church leaders until a time when the Irish Church was mostly controlled by Rome.

Women carried out much of the back-breaking work in pre- and early Christian Ireland. Brigid’s nuns are also very agile and productive, doing farmwork and smith crafts, but we see noticeable changes brought about by the new morality of the Christian church. An early tenth century glossary – ‘. . . of a Bishop Cormac mac Cuilennain points out that in his day the water mill had replaced the female slave in this regard, though slaves remained a part of Irish society’. Hand querns were used until the sixteenth century when Moryson, the Elizabethan historian visits Cork noting: ‘I have seen with these eyes young maids stark naked grinding of corn with certain stones to make cakes thereof’ (Simms p. 456 [88]). Baking bread was a housewife’s duty, the women noted for being quarrelsome – perhaps hot and bothered. Much earlier, women would wash and dye clothes at the river. Needing to stamp on them, they were forced to hold up their skirts – thus – ‘. . . since the Life of Ciarán of Clonmacnoise it is held improper for men to be present in a house where cloth was being dyed’ (Simms:457 [95]). Furthermore, ‘It even appears that apart from the strictest monastic communities, it was considered shameful for a man to milk a cow’(Simms:457 [93]).

So, were women’s rights increased with the arrival of the Christian church? There are pros and cons but generally, over time, women’s rights continue to depend on their status, as property and marital status continue to govern the lives of all people.

In the seventh century, Abbot Adomnán of Iona persuaded his royal kinsman from the Cenél Conaill and a host of clerical and lay rulers to ‘. . . accede a country wide Law of the Innocents, protecting non-combatants, specifically women, clerics and underage boys, from being attacked or killed, with fines for any violent death of a woman being paid directly to the Abbot of Iona’ (Simms:409). Finn of the Fianna sagas also warns others to be courteous to women and household servants. As Christianity moved into the late Middle Ages, attitudes toward women worsen. Men, especially clergy were warned of ‘women’s innate evil’, no doubt due to their own fight with temptation, as celibacy became the law. A king of the Northern Uí Néill in this time, was directed to – ‘Esteem the clergy, keep control over their dwellings, protect then against women, good noble son of Niall’ (Simms:279).

We see in Bethu Brigte several queens who came to Brigid to ask for favours, such as blessings for fertility and love spells. These women had a degree of power and status; some even ruled in various capacities. In time the church became as powerful as monarchs. Simms notes a comment by a Friar Clynn as being ‘. . . seen as the typical misogynistic view of a clerical writer in the Middle Ages, blaming all women from Eve onwards for leading men astray, and he cannot be acquitted of responsibility for the interjection ‘as usual’ (Simms:118). Rev. John Ryan in his History of Monasticism says that – ‘With the growth of monasticism in the strict sense, under St Finnian and his disciples, women became objects of suspicion, and the relation between the sexes henceforth was one of rather distant cordiality’.

Telli illuminates the relationship between druids and early Christians within families, as conversions are inspired by Brigid’s deeds and the holy aura emanating from her. The druids in the early scenes linked to her mother, the slave Broisech, facilitate recognition of Brigid’s special powers and gifts. One druid ensures her saintly identity by naming her Brigid, a lineal connection to the old beliefs as authorization by the priests[druids] of the old order.

Telli suggests that traditional, native ideas about heroes may be a model used for bestowing upon Brigid a ‘superhero’ status. Being born halfway inside and outside also echoes the liminality of heroes in Irish sagas who are peculiar and marginal to the earthly human realm. Telli also explores the notion of motifs that are employed in the narrative, such as ‘impure’ pagans as opposed to the ‘purity’ of a Chrisitan and a ‘red cow with white ears’ must provide nourishment to the child Brigid. Such creatures she says are borrowed from the pagan past and ‘. . . were connected with the power of the unseen, supernatural world’ (Telli:13). Telli believes the descriptions of fire emanating from Brigid or used in crafting and cooking – art and fire- are purposely emphasized by the author because he/she ‘. . . wishes the vita to occupy a liminal space between Christianity and paganism by using motifs that are pertinent to both and thereby builds a bridge towards a new concept of religiosity’ (Telli:14).

Telli speaks of static character, describing Brigid’s character development as contrasting with other saints, for example Saint Martin of Tours, whose characters remain static through the vitae, many of which will not contain supernatural elements in their stories. She emphasizes character changes as Brigid matures, travelling around Ireland, earlier being ‘fractious and confrontational’ especially with her father. Grace intensifies as she gains respect and followers, becoming a more sagacious woman regarding the responsibilities of leadership. She is mindful of ‘female subordination’ when conferring with the bishops Patrick, Ibor and Mel. Though disobeying her father and laymen, she follows orders from these religious superiors, but it is proven that her devotion and holiness can be superior to theirs.

Symbols associated with Brigid tell a complex story:

Here are some lines from the poem ‘Cill Aodáin’ by Antoine Ó Raifteiri (1770-1835)

Anois teacht an earraigh

Beidh an lá ag dul chun síneadh

‘S tar éis na féile Bríde

Ardóidh mé mo sheol

Cill Aodáin an baile

a bhfásann gach ní ann

Tá sméara is subh craobh ann

is meas de gach sórt

Now with the coming of spring

The day will be lengthening

And after Brigid’s feast day

I will raise my sail

Cill Aodáin is the place

where all good things grow

Blackberries raspberries,

a myriad of fruits

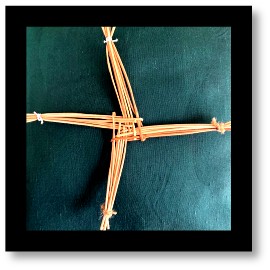

The poet symbolizes his return home, as the raising of a sail, the coming of spring and by descriptions of crops growing. St Brigid is associated with the beginning of spring, the feast of Imbolc, the lambing season, the hearth that gives protection to home and family. The tree was also important to Brigid, especially the great Irish Oak where she built her monastery on the Curragh of Kildare and the oaks from which she built her beautiful church. The willow or saileach in Irish too is symbolic, a tree shooting branches from the ground from which still today people make woven crosses to hang above doorways, the thresholds between spaces, as protective blessings. The fertile limestone-based ‘Curragh’, her place of worship and habitation was rich with growth and abundance, evident by the produce, fecund in her miracles. Keeping in mind that though Brigid or someone of her ilk was a real person, she will always be part of the enigma that conflates the Christian saint and the pagan goddesses who preceded her. Therefore, elements of the holy virgin’s life will be merged with those goddesses.

Brigid is in ancient Ireland, not Europe. Her interactions are carried out amidst the lingering pre-Christian sagas, stone monuments, wild, mist-filled landscapes and for many years to come, pagan Gaels in heart and mind.

Selected Bibliography

Two Lives of Saint Brigid, Edited and Translated by Philip Freeman, Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2024

CELT project_Bethu Brigte_University College Cork, HTML Document. (Date 27/04/2015)

Lili Telli, Narrative Analysis of Bethu Brigte: Variant of my Article ‘Narrative Analysis of Bethu Brigte’ in Narratio Aliena?, Vol. 7 – Narrative pattern and genre in hagiographic writing: Comparative perspectives from Asia to Europe, Ed. Stephan Conerman, 2014 (Academic Paper)

Tracy Newlands, (2000). ‘Ban: An Alternative Model of the Impact of Christian Conversion on Women in Irish Society‘, (pp. 429-439). In Origins and Revivals, proceedings of The First Australian Conference of Celtic Studies. Geraint Evans, Bernard Martin & Jonathan Wooding (Eds.), Centre for Celtic Studies University of Sydney, 2000

Elayne Kaye, (2000). ‘Women and Power in Early Irish Literature’, (pp.223-237). In Origins and Revivals, proceedings of The First Australian Conference of Celtic Studies. Geraint Evans, Bernard Martin & Jonathan Wooding (Eds.), Centre for Celtic Studies University of Sydney, 2000

Katharine Simms, Gaelic Ulster in the Middle Ages: History, culture and society, Trinity Medieval Ireland Series: 4, Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2020

Jules McCue is a Wollongong based artist, musician, writer, teacher, and independent researcher. She has written many essays about artists and their work, for example: Extraordinary Exhibition: Holy Threads: Savanhdary Vongpoothorn, [1998]; Black Man in a Whiteman’s World: Indigenous Art in NSW Jails [1998] ; Allan Mansell: The Creation of Visual Stories from an Original Tasmanian [2012]. Her Masters Dissertation: Wildflowers and White Porcelain and Circles and Seeds: a study of the History of Women Artists through Still Life Painting [1994], University of Wollongong. Conference Papers include Not Surrealism, Magical Realism [1995], Katheen and Kitty: Two Women; a painter and a composer/pianist, both of Irish heritage [2019], and Historical Ireland: control and cadastrophe through stories of circumjacent mythology, weird and wonderful, ambiguous shapings of the vigorous mind [2021]. Email: julesmacarts@gmail.com Website: julesmccue.com