A Profile by Josepha Smith and Frances Devlin-Glass

The first part in this series, Family’s Our Way of Life’, detailing Mary’s birth and life in Ireland and England prior to her emigration to Australia, was published in last month’s Tinteán.

Arriving in Australia

The only rough part of the long journey on the Fairstar to Australia was the Bay of Biscay (she’s only human). Disembarking, she was met by Wilfred Green, a Kyneton hospital board member and the sponsor of her emigration. She was given the ‘red-carpet treatment’: the matron was at her accommodation, Campaspe Lodge, when she arrived. A sailor, the father of a child Mary had delivered in Portsmouth, had a friend, Nesta (Ernesta or Ernestina) McKellar, in Kyneton. She and Mary shared the experience of living on the land, and Mary cherished having a friend with country sensibilities in Kyneton. She would later tend her as she died. As well, three doctors welcomed her: Joe Connellan, John Connell and Brian Cohen. Joe Connellan was ‘a family man and a gentleman’. John Connell was ‘strong and argumentative’. Brian Cohen, by contrast, was ‘quiet and needing protection’.

They were a team of 10 nurses, and they bunked in a very comfortable nurses’ quarters in an old bluestone mill, doing general nursing and midwifery. Mary would later ‘a little accidentally’, specialise in palliative care: tending the dying was also to look after their loved ones. If she found someone who was devastated by someone’s death, for example, she’d stay with the bereaved, offer them a glass of wine and a massage. Someone commented that the Irish blessing was ‘Mary in a nutshell’.

Her first impressions of Australia were different from those of many emigrants. The landscapes she encountered were not formidable or alien, and she thinks that was because when she came to Kynetno when the country was green, and more importantly, the people she met and the way of life were familiar, especially the busy life of a nurse in a small community. What she noted was the change in scale with everything bigger – fields, farm machinery and distances. Asked to compare the ways of life as a farmer in Australia and Ireland, Mary felt that there was more comradeship in Australia than she’d experienced at home, and she found people more hospitable towards strangers, and those who came visiting. People invited her out continually. They were unpretentious and welcoming, and she reports never being bothered by sectarianism. She believes small village life in Ireland was a good foundation for getting on with the neighbours (indeed, on her return visits to Roscommon, she visits the neighbours as a matter of course). Then, she imagined she was in Australia for a short time. It’s now over 60 years since her arrival, and she expresses the view that it was a ‘fortunate choice to come to Australia.

Nursing in Kyneton and the Outback

One of her early gigs in Australia, in 1961-2, was a year-long stint with the Royal Flying Doctor Service in Cloncurry (far north-west Queensland), where she worked at another 30-bed hospital, the focus for the whole area (excepting Mt Isa which had its own hospital). In addition to working with Dr Harvey Sutton (the town doctor and a legend in his own lifetime), she was sometimes co-opted to fly with the Flying Doctor Service, which had its headquarters in Cloncurry. The resident Flying Doctor happened to be another Irishman, Timothy O’Leary, a friendly, laid-back character. He both flew and doctored, and she would sometimes be dropped in a town to wait for the doctor’s return from remote stations: she would triage patients while awaiting his return. Her cases were mainly midwifery, and accidents on motorbikes and horses. It was not glamorous work, and conditions in these dusty little towns in remote Northern Territory, on the Barkly Tableland and the Gulf of Carpentaria in Far North Queensland, were testing but she enjoyed it, visiting many remote places like Daly Waters, Katherine, Tennant Creek, Normanton, Burketown and Borroloola by plane. She often ministered to Indigenous people. She found them welcoming, and she notes that the medics treated their Indigenous patients equally: there was no thought of putting them at the bottom of the patient list. Cloncurry, despite its nine pubs (for a population of around 2000), she experienced as a quiet place. She didn’t have access to a car, common in that era, so her life revolved around nursing. Women were in short supply in Cloncurry and men were, unsurprisingly, drawn to her.

Marrying Tom, and Mothering

She was keen to return Kyneton after her stint as a remote nurse because of the privations of the outpost, (not that she complained about that) and she missed her friends in Victoria. Predictably at a dance in Kyneton Town Hall, she met, one, Tom Walsh, a potato and lamb farmer. In addition to being an only son, a farmer looking for a wife, he was an outstanding musician, a ‘good dancer’, ‘pleasant’, and the youngest of three of a family with three older sisters. After a one-year courtship they were married in a quiet ceremony with friends in Kyneton’s Our Lady of the Holy Rosary church in 1963 by Fr Michael Sheehy, the parish priest at the time who happened to be from Kerry. Fr Michael made a point of visiting Mary’s mother when he visited Ireland prior to the wedding, a great honour in those days and great consolation for her mother Kate who missed her daughter greatly. Her wedding outfit was unconventional. A traditional white costume was not for her, and she wore a stylish cocktail dress in royal blue with a cape, matching fabric bows on her shoes and a fascinator with netting for a hat. The outfit was an original by leading Collins Street couturiers, the Misses Mooney. Mary was always in style.

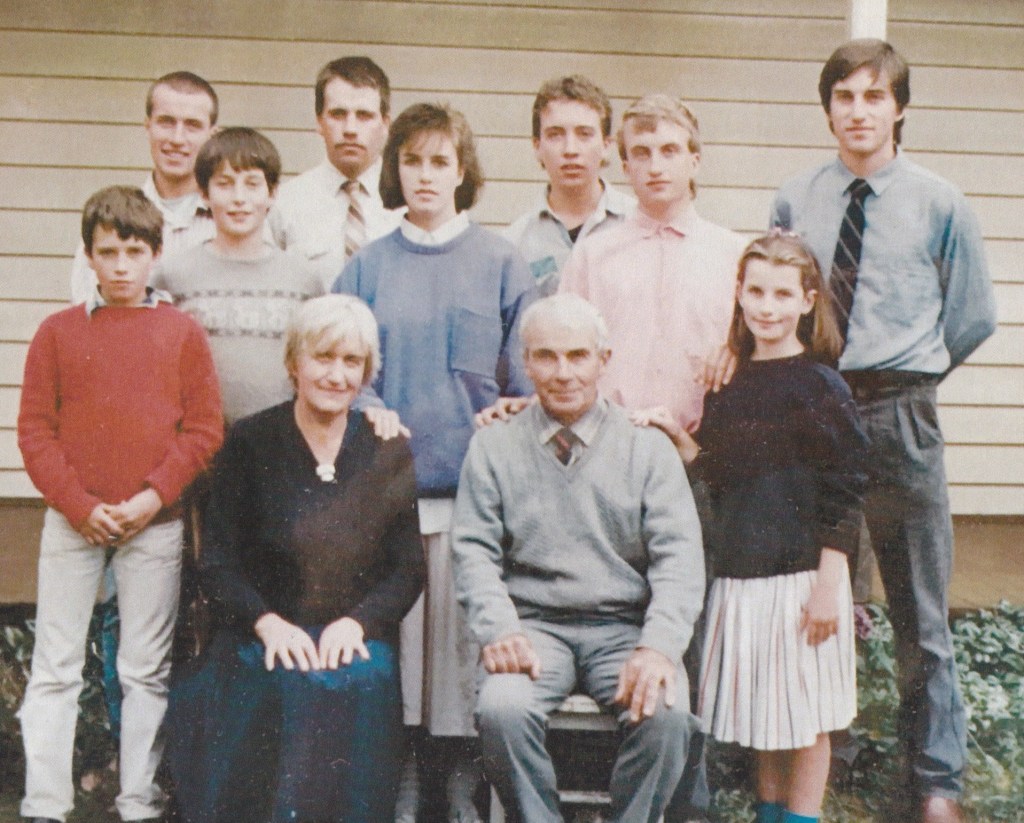

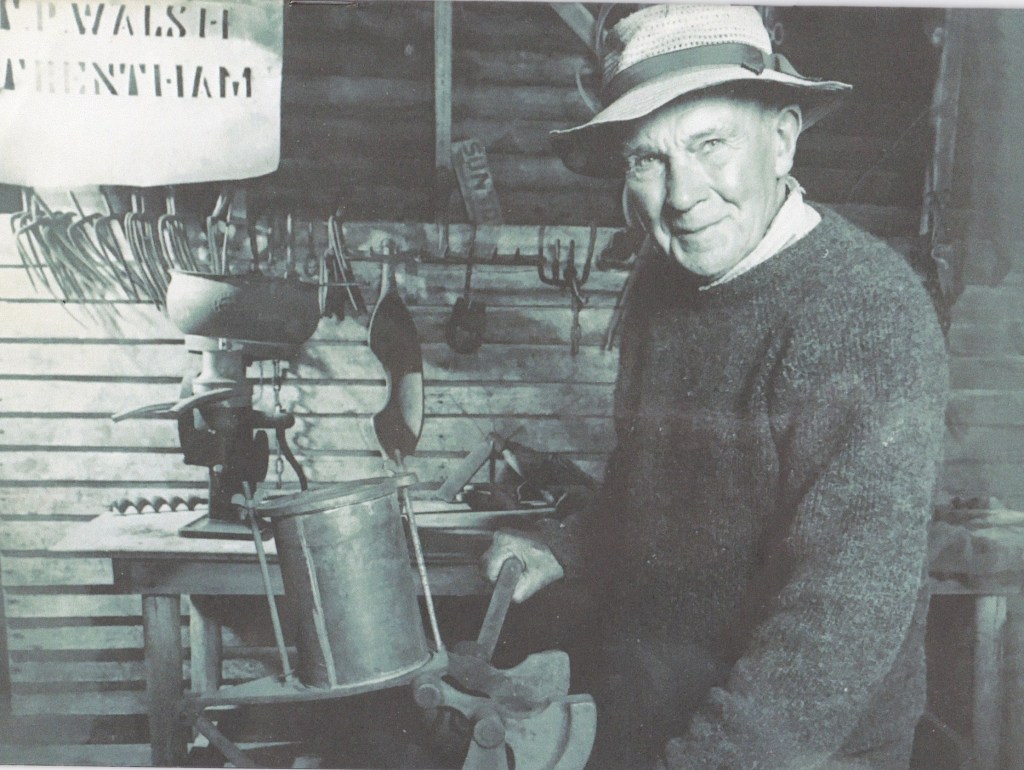

Four generations of Walshes have lived and farmed in what is now Mary’s farmhouse, a museum devoted to honouring the family. A gentle man, and respectful, especially of women, Tom along with Mary would in time raise nine children on the Trentham farm (Thomas, Patrick, Eamon, Matthew, David, Caroline, Denis, Simon, Madelene).

Tom weathered the millennial drought as a spud and sheep farmer because of his faith in his patch of ‘God’s country’, boasting that he could grow anything, even chocolate, if he’d been allowed to get the seeds. Her role as farmer’s wife was mainly as another pair of eyes for Tom: noting when the sheep were in the wrong paddock, closing gates inadvertently left open, looking after the chooks, gathering the eggs, and collecting and distributing milk and butter. She managed the kitchen for her big brood, and hospitality for visitors. Mary’s go-to meal was lamb seasoned with Tom’s fresh green herbs and spuds, or bacon and cabbage, cooked in the Irish way. Felix Meagher noted there was always a big pan of spuds to be mashed to accommodate extras. Son Denis remembers her as a ‘fantastic chef’:

We would all be working on the farm when not at school and there was a clear routine of morning smoko, and afternoon smoko which was often brought to the paddock or wherever we were working (shearing shed or potato shed or stooking hay or marking lambs), and down tools for a very large tin tea pot plus some home-prepared goodies. More often than not the midday meal was hot ( a complete roast meal or something else, always wonderful), these were mostly prepared on a wood stove so a bit more required than turning on the electricity or gas stove.

Like Mary, the children enjoyed farming with Tom, and were early adepts at driving and operating farm machinery.

Music-Making

Music was how the family recreated. Tom’s mother, Alice, was a musical woman and she encouraged her extended multi-generational tribe of musos, but Mary enabled from the sidelines – always there, and always supportive. Tom was an ace musician, a fiddler, and a dancer, and was joined by several of his children who were also multi-instrumentalists and gifted: Madelene specialises in tin whistle, piano and singing, Denis on his guitar and bazouka, fiddle and singing, Patrick on the button accordion, Caroline on fiddle. Patrick, Eamon, Matthew and David all played Brass in the Kyneton Brass Band (in particular, trumpet and trombone). Mary also did a lot of ferrying of the children to music lessons, band rehearsals, choir practice, and performances. The eldest five boys were all in the Kyneton band which practised and performed regularly, and some of the children were in the National Boys’ (and Girls’) Choirs. These commitments entailed a demanding round trip for Mary of over 200 kilometres every Friday night to Nunawading High School or Kew.

The Walshes were foundation participants in the Lake School of Irish Music, a summer school for musicians in the Irish oral tradition which occurs annually in Koroit in early January. Today Felix Meagher, a tyro in the Irish music scene in Australia and the founder of the School, who knows Mary through her musical family, reports that Denis, Mary’s son, was the first to attend the school with his family and that subsequently, they were serial participants. In this family, music-making is multi-generational, with grandchildren and cousins being part of the sessions in Trentham and Blackwood and the neighbouring towns. Tom played for dances until a year before he died, aged 91. The Walshes are fiercely Irish-identified. They are Catholic as well, but don’t parade it, according to one witness. However, she has the nurse’s interest in new emerging saints who endure tough physical health conditions, such as the new Italian teenage ‘gamer’ saint, Carlo Acutis, the first in Pope Leo XIV’s pontificate.

When Tom died on 17 April 2018, people came from every quarter of the country to attend the biggest funeral Trentham had ever seen. An outdoor broadcast accommodated the spillover. He was 91 and had been active until six months before he died. The priest began Tom’s funeral service by saying ‘what a great day for a collection!’ It was a back-handed compliment, but Mary, ever loyal to Tom, and feisty, was unimpressed.

Nursing Again in Trentham

When her last child was in kindergarten, Mary returned to nursing. In Australia, Mary found new sources of inspiration in local women doctors, in particular, an eccentric and heroic doctor, Gweneth Wisewould, Trentham’s first woman doctor, who trekked into difficult hilly and wooded country in central Victoria for 30 years to give medical care under all manner of conditions, including snow and extreme heat. Gweneth would later become the subject of a biography, Outpost: A Doctor on the Divide, by Elizabeth Berzkalns (2019). Another role model was Sydney-born Dr Catherine Hamlin , a pioneer in the treatment of obstetric fistulas who founded hospitals in Ethiopia and lived there for sixty years.

Mary delivered many of the Trentham babies, and later she was in demand for aged care. Her son, Denis, remembers that in her older years, she looked as though she might never retire from Trentham Hospital. When asked what kinds of nursing gave her most satisfaction, Mary answers she enjoyed it all. She said Palliative care became more talked about toward the end of her time in the profession and officially that was her last position, but it has always been a part of the job. When her elderly friend, Nesta McKellar died at home, her son Denis remembers Mary taking her children out of school to say goodbye after she was laid out in her home. He understood then something of her ‘gift with the dying’ and her reverence for dying with dignity, as a form of honouring the life and a practical instance of ‘Céad Míle Fáilte’. Mary enjoyed going to the heart of what was needed at every stage in her career. Seeing that, tending to that, was her vocation. She is too Irish and Australian to blow her own trumpet but the stories passed around from families who have received her care convey acts of such generosity genuine help – the kind of intimacy that people want and need when at their most vulnerable, and Mary was and is there for it. Many of those stories are reminiscent of the story of Sr Mary Aikenhead, founder of the Irish Sisters of Charity who opened the first Catholic Hospital in Ireland since the reformation. The story goes that the first operation in that hospital involved a little boy lying in Sr Mary’s lap for the entire procedure. Seeing and responding to need with pragmatism and heart – something for which Irish Marys are adept, it seems.

The farming, hospitality and nursing traditions of the Walshes continue into the next two generations. All the people we consulted talked of her influence in her community, and we saw evidence of her celebrity and the respect she had earned as we chatted around the fire at her house, and later at the Redbeard café, run by grand-daughter Charlotte. A constant stream of visitors came to say hello and greet her warmly, including two random young Irishmen whom a relative had brought from Bendigo to the farm to meet her. Mary is hospitable, kindly, welcoming, and a magnet for good craic, an understated pillar in the Trentham community, and much-loved.

Jo Smith and Frances Devlin-Glass

Jo is Irish-born and lives in the Trentham district. Frances Devlin-Glass is a member of the Tinteán editorial collective.