Photos by the author and Brian Lynch.

A Writerly Traveller’s Tale by Gay Lynch

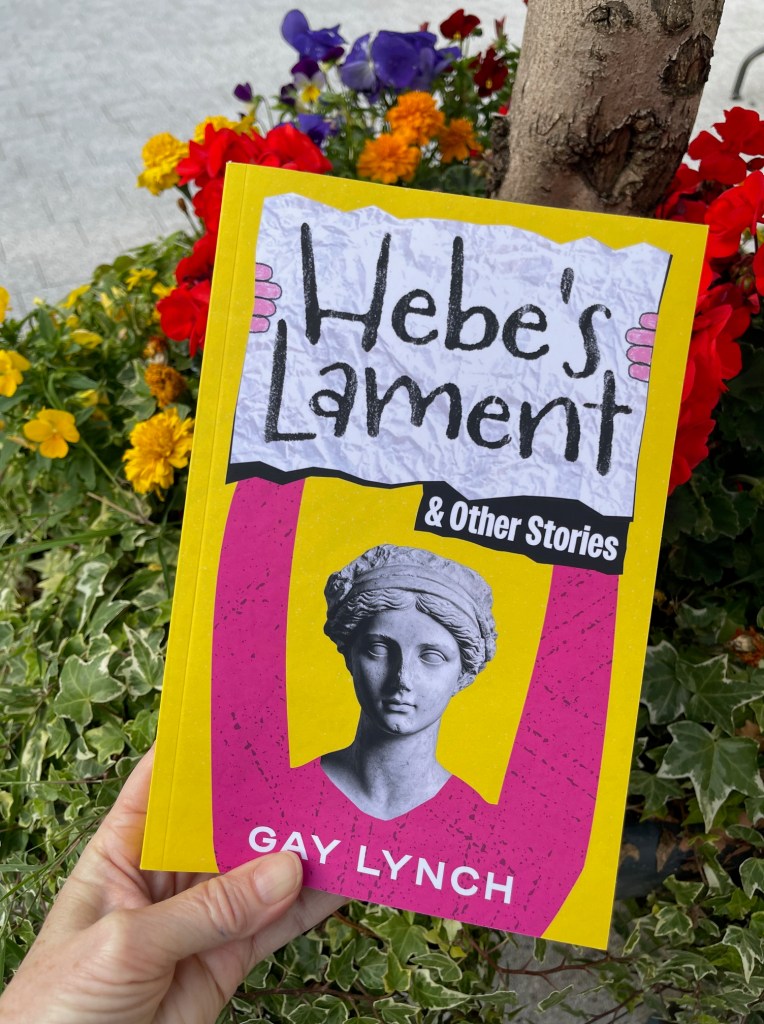

In June in Killarney, I attend the 17th ICSSE (International Conference of Short Stories in English), themed ‘How it Works, the Uniqueness of the Short Story.’ During the conference, I launch Hebe’s Lament & Other Stories (2025) a collection of my published stories, including ‘A Good Girl from Graigh na Muilte Iarainn’ (Woodford, Galway), prequel to my Irish frontier novel Unsettled, reviewed in this journal.

The week preceding, my Lynch husband attends the 2025 Killarney Bridge Congress as partner to a nonagenarian from Galway, who gifts him a bottle of Holy Water and several of her paintings. At tournament end, she thanks me for the loan of him and tells me that he is ‘a darling man.’ Perhaps the water went to her head but then Killarney is a magical place, and Lynches proliferate in Ireland.

When I arrive at the conference reception drinks, avid with love for a dark, new, metafictive novel Writers Anonymous that I’ve demolished in fewer than twenty-four hours, I nudge Cork writer Madeleine D’Arcy Lane to ask about its author.‘ Will you point out William Wall? I hear he may be among us.’ The intelligent blonde woman, paused by me in her conversation with Madeleine, says, ‘Oh come with me, I’ll introduce you. He’s my husband.’

Meeting my footnotes delights me. I tell William how the characters’ problems subsume and devastate me – the murder of a seventeen-year-old, a student scamming a mentor – how the clever twist in his plot intrigues and shocks me, how I’ll remain awhile inside the mind of his Irish writer-protagonist Jim Winter in this thrilling, writerly book.

Each day, I drag my bones away from the conference room, balcony view of Kelly-Green fields, of mountains shrouded in ethereal cloud, of fallow Red Deer, present in Kerry since the Ice Age, and Japanese Sika deer, heads raised mid-rumination as if to whiff on the soft breeze, a scribble of storytellers. I run through misty rain across the bridge, and over the River Fleskand flats, following the path into town. Sometimes, for variety, I run towards white swans gliding past Ross Castle, a fifteenth-century tower house on the edge of Lake Leane.

On an expat birthday, we four Dr-writers and one Dr Sawbones, set off at dusk to board Damien’s jaunting jinker pulled by Maggie, an Irish Cob in harness; to clop along forested laneways to Muckross Abbey. Our joy and loquacity expand proportionately when I conjure bottles of Prosecco from my book bag. Factual premise or not, we pay homage to the oldest tree in Ireland, a 500-year-old Yew planted by monks. It looks sad in the shadowy cage of its courtyard, balding with age, as it gestures towards filtered light.

After the wind and climb towards the MacGillycudd’s Reeks and the Aghadoe Heights Hotel, which loom over Lough Leane, we share a long langoustine lunch with poet, librettist and glorious songstress Jennifer Liston, soon to launch Grace Notes: Giving Voice to Grainne Mhaol Irish Pirate Queen a verse novel about that brilliant seafarer, chieftain, contemporary of Elisabeth 1. We have engineered a Lakes of Killarney reunion with her and her husband, Adelaide photographer Robert Rath, who deep dives in sea and lake just for the wonder of it, and so that Jen and I might raise our glasses, sláinte, as we swap new books on the dining room balcony.

Imagine a garden launch for my story collection, at Gleneagles Hotel run by local writer Eileen O’Donaghue, a generous speech by South Australian short story writer Rebekah Clarkson, before I read from my Proustian story ‘M’ (2017) set in the Grand Hotel in Cabourg, where Marcel wrote In Search of Lost Time (original French: À la recherche du temps perdu.

Imagine I stop reading ‘M’ on the cusp of in flagrante delicto to encourage listeners to buy their own copy and read on; and that Irish literary nova Nuala O’Connor tells me next day, that she did – read on – and believes the secret lover is not the protagonist Matilda’s boyfriend but one of Proust’s ungrammatical lift boys, much-maligned by the great man for removing the personal pronoun from the beginnings of their sentences, not unlike contemporary writers of text messages.

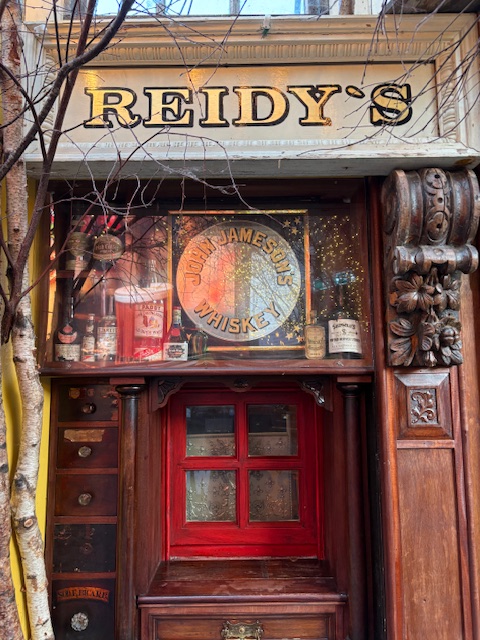

Writers and quizmasters Jamie O’Connell from Bean & Batch Café in Kenmare, and Eileen O’Donaghue proprietor of Gleneagles, who run the conference literary quiz night at Reidy’s Pub, dream up questions obscure enough to fox teams of English professors.

Kerry wool shops and triple-distilled, Irish whiskey entice me from the High Street, a portrait exhibition at Killarney House & Gardens, dry stone walls along Rookery Road, foxgloves and fuchsias erupting wild on the verge. My dream of donning a falconers’ glove, onto which birds of prey sweep down from the sky and land on my wrist, materialises. Imagine looking owls and goshawks straight in the eye.

Éilís Ní Dhuibhne, a generous conferee with quiet authority, brings from home copies of her books for my friend. Two months later, the Arts Council, An Chomhairle Ealaíon, installs her as Ireland’s Laureate for Fiction, to succeed Colm Tóibín, Sebastian Barry, and Anne Enright. Ireland, where historically duels took place in poetry, takes care of writers, especially since its successful three-year pilot program, now legislated as a Basic Income for the Arts (BIA), a living wage (1400 euros per month), so creatives can better focus on their work.

The ballroom bonhomie at the farewell dinner, the hugs and high five between writers from four continents, the closing address of director Professor Maurice A Lee, who proclaims it perhaps, after all, ‘the best conference ever,’ the natural beauty of Killarney – how I will miss it and this storied community. The raking of a pot of tea in a cosy lounge with Irish writers, Evelyn Conlan and Nuala O’Connor, beloved in Australia, and the surety of my return console me.

The counterbalance must surely be the so-called ‘conference cold” I had tried so hard to avoid, as I moved furniture between me and the contaminated, changed the order of conferees on panels I chaired, and sat further away from virulent speakers. And so, when I travel on to Bordeaux to seek the writing place of essayist Michel de Montaigne, Covid lays me flat on a French chaise for a week, feverishly dreaming of Killarney.

Gay Lynch

Adjunct to Flinders University, Gay Lynch writes essays, novels, papers, reviews, short-stories, on unceded Bunurong lands.

In 2025, she judged the Creative Prose Prize, AAALS (American Association Australasian Literary Studies), which she had won in 2024; chaired and conversed on panels at the ASSF (Australian Short Story Festival); published YA novel Harm None; and flash pieces in ‘The Darling Exchange’ (Kill Your Darlings) and This is What it Feels Like (Recent Work Press).