A talk for the Camperdown Celtic Festival, 28 June 2025 by Pat Walsh (alias Padraig Breathnach) at the Leura Lodge Masonic temple

A talk for the Camperdown Celtic Festival, 28 June 2025 by Pat Walsh (alias Padraig Breathnach) at the Leura Lodge Masonic temple

It’s appropriate to remind ourselves that we are meeting this afternoon on the traditional lands of the Djargurd Wurrung people. This building is called Leura Lodge after Mt Leura which was also a significant place to Djargurd Wurrung. Further, the recent Yoorrook Walk for Truth from Portland to Melbourne stopped here in Camperdown to remember two leaders: the Djargurd Wurrung Aboriginal leader Wombeetch Puyuun, whose obelisk dominates the Camperdown Cemetery, and the remarkable Celtic/Scottish gentleman James Dawson, who erected that monument. And two words of special thanks: first to the Freemasons for allowing us to use these historic premises. Using this lodge to celebrate Rabbie Burns (1759-1796) makes sense. Burns was a dedicated Freemason, in fact a Master Mason. Second, a very big thankyou to the wonderful Catherine O’Flynn who organises the Festival and fitted me in today. My only regret is that across the road at the Camperdown Historical Society right now Eugene von Guerard is being discussed. I’d love to hear what is being said. I have a print of von Guerard’s painting of Lake Purrumbete on my wall at home and I included in the Walsh family history a photo of his extraordinary painting of Indigenous people in the Stoney Rises in 1857 not long before my Irish ancestors settled there.

The proposition I am playing with today is based on reflection about my experience. It may not fit your experience of course. And even if the cap fits, don’t feel obliged to wear it! My thesis is two-part: one, that media and a changing cultural landscape bit by bit assimilates, homogenises, dare I say colonises, us away from our roots and possibly affects our sense of direction and orientation, leaving at least some of us amorphous, shapeless. Two, that there’s a lot to be gained from re-discovering (but also critically analysing) our Irishness, including its Catholic dimension.

Where’s Paddy?

So I’m asking ‘Where’s Paddy gone?’ I’ve borrowed the title from a story that Margaret Walsh, my cousin’s partner in Ballarat, told me. Margaret grew up Catholic around Warrnambool. She remembers elaborate Benedictions at Kirkstall, a small mainly Irish farming settlement near Koroit – the candles, gold monstrance holding the large white host, smoking thurible, sweeping vestments, organ, hymns. She also recalls one unforgettable Sunday night, when disaster struck. An altar boy holding a candle accidentally set fire to his surplice, only to be saved by an unlikely but quick thinking member of the congregation, the subject of this little tale. This fellow, according to Margaret, was often intoxicated and thought to be under the weather that night, but still had enough of his wits about him to jump up from his seat, rush to the front door of the church, grab the holy water font and return to throw its contents all over the altar boy and douse the fire. It doesn’t take much to imagine him re-telling the story to fellow-drinkers over and over down the years adding detail and flourish until it was near unrecognisable and listeners would believe he had single handedly saved the church and its parishioners from a conflagration raging like hell itself. Margaret said he was one of five, always seemed to be poor, smelly and intoxicated. She recalled her dad taking a cut of meat to the family whenever he killed a sheep.

Margaret also relates that at his brother Paddy’s funeral in Tower Hill, this hapless fellow was distracted talking to people near him (probably about how he’d saved the life of the altar boy) when the funeral director released the straps holding Paddy’s coffin. Our erstwhile man-of-the-moment suddenly realised Paddy had disappeared. Paddy was nowhere to be seen. Alarmed, he called out in shock: ‘Where’s Paddy gone?’ ‘Where’s Paddy gone?’ Margaret says everybody at the funeral had a hell of a job trying to stop laughing, including her dad. And all the way home in the car, her dad kept calling out ‘Where’s Paddy gone’.

Paddy: Irish and Catholic

We all know that Paddy is a nickname for someone who is both Irish and a Catholic. The two used to mean much the same thing. So when I heard the cry ‘where’s Paddy gone’, it started me thinking about my own childhood in South Purrumbete, where I grew up the descendant of Irish immigrants (one from County Tipperary, the other from County Kerry), named ‘Patrick’ by my mum and dad and grew up Catholic as automatic as being zoned to barrack for Geelong. And – very aware of the big changes that have occurred in just my one lifetime – I asked myself where’s all that gone, both the Irish Paddy and the Catholic Paddy?

It’s also a question I’ve only asked myself in recent years…. that last chapter of life when we have the time to reflect, to learn from our past and to really get to know ourselves from the high ground of age which allows perspective.

In his beautiful novel Time of the Child, about an Irish village which could be South Purrumbete, the Irish writer Niall Williams writes: ‘the purpose of aging is to grow into your soul, the one you have been carrying all along’. Even though the Walshs are not indigenous Irish (we came from Wales during the Norman invasion and Walsh in Irish is Breathnach which means foreigner), I still believe that my soul is largely Irish and that – as Williams says – I’ve been carrying it all along but without paying it much attention or working at growing into it.

Purrumbete

Margaret Walsh’s story brought back many memories of growing up local Irish Catholic in South Purrumbete. Let me recall some.

First, there’s the church itself. Our church in South Purrumbete was named St Brigid’s after the patroness of Ireland, Patrick’s counterpart. It was opened in 1936 and sits at the entrance to Walshs Rd which seems right because it had a central and special place in the community and the Walsh story. My parents were the first to be married there (though the Darcys like to dispute this!). Numerous Walshs from my family across at least four generations were baptised, blessed, married, ticked off, forgiven, prayed over and buried from that place.

As St Brigid’s was an outstation served from Camperdown, priests used to regularly come to the home of my grandpa, Maurice Walsh, who lived near us in Walshs Rd. The son of the Irish immigrants I mentioned earlier, he and his wife Bridget (Moran) would serve them lunch after Sunday Mass. If a Redemptorist priest billeted at Grandpa Maurice’s while conducting a mission, our Aunt Dorothy, mother of Peter O’Sullivan (well known in this town), told us that she and her brother Cyril ‘would work for ages in the garden, helping mum (Bridget) get it spick and span’ for the visiting VIP.

Peter, my oldest brother, told me that on one occasion, Grandma Bridget asked him to accompany the visiting Mission priest on a sort of local inquisition. His job was to point out the homes of Catholics who were not regular Mass goers so that the priest could urge them to attend the Mission and change their ways. Not comfortable in the role, Peter reckoned he couldn’t remember who he dobbed in. And that to avoid being seen, he kept his head down below the dashboard of the priest’s car…..

St Brigid’s replaced a smaller church which was decommissioned in 1936, bought by my dad and relocated to our farm for use as a shed. Ferrelli Pasquale, the Italian POW who worked on our place during the war used the former sacristy as his bedroom. Much later, Peter’s kids burned the old church down (accidentally, not because they were anti-Catholic).

Sunday, with sporty Saturday a close second, was the most important day of the week. Like voting and paying taxes, Mass was obligatory. Our Irish great grandma, Margaret Walsh (O’Brien), is said to have walked fasting across the paddocks to Mass in the old church. Our Grandpa Maurice also used to walk to the new church. If their car wouldn’t start, Bill and Queenie Horan drove their tractor. Mum would see Eddie Jones car coming around Hallyburton’s corner, and call out, ‘Hurry up or we’re going to be late’.

During pre-electricity days, Mum recalled that Jack Horan would drive past our place to pick up her, John and Peter for choir practice at St Brigid’s. Jack would have a pump-up Tilley lamp already lit and hissing loudly in the back of his car ready to illuminate the dark church. Sunday Mass was also a public social event.

On Saturday night, us kids would have our one bath of the week. The next morning, we dressed up to please God but also to show our family in the best light. Our ‘good clothes’ had to be taken off after Mass and put away. Having fasted from the night before and possibly helped with the milking or got the wood in, us kids were pretty hungry and irritable by the end of Mass. ‘Don’t be fighting now’, Mum would say, ‘You’ve just been to Holy Communion’.

Working in East Timor, where Sunday Mass is a weekly highlight, I smiled to see the same tradition at work long after it has gone from Purrumbete. Other Holy Days of Obligation that occurred during the week took precedence over school. Catholic kids like us would spend the morning of Ash Wednesday at St Brigid’s, not at class at our state school down the hill. Mr Graham, the school teacher at one time, did not take kindly to these absences. Fair enough I suppose. We were supposed to be learning the 3 Rs. But, turning up late, us Catholic kids would be put to work in the school garden and not allowed into the classroom. I doubt we complained, but I think we sensed that a hint of sectarian discrimination was at work. It was certainly well and truly entrenched in the wider society.

I like to think the Irish flag is a perfect pictorial representation of South Purrumbete back then. The Irish flag is pleasingly, but perhaps surprisingly, welcoming and inclusive. It has three stripes: a green panel at one end, an orange one at the other, and in between a white strip. Isn’t that Purrumbete! The Catholic St Brigid’s on one hill, the Prebyterian church across the valley on the opposite hill but in between the neutral, white stretch that, back in the day, was the butter factory, footy ground, school etc where the orange and the green met and collaborated happily.

A Melbourne friend of mine told me recently that when he went for a beer at the Mt Noorat pub, he quickly learned that the regulars had their fixed spot at the bar which no-one could take even if the regular was not there. This meant, he reckoned, that even to talk to his brother-in-law, he had to yell the length of the bar. Brian Darcy, who’s here today, told me that he came across the same rule in Ireland but realised that deeper factors might be at work. At one session, his Irish drinking companion indicated a bloke down the other end of the bar, and said to Darc in a low voice: ‘Don’t be drinking with that fella now.’ ‘Why’s that?’, asked Darc. ‘He stole a bale o’hay off me 20 years ago….’ As Darc said to me, ‘For one minute I thought I was back in Purrumbete!’

A similar regime regulated seating at Mass on Sundays. In a delightful passage in Time of the Child, Niall Williams describes Mass on a Sunday in 1962 in the Irish village of Faha. ‘One of the comforts of ritual’, he writes, ‘is immutability and any parishioner could have set the congregation into the pews like the pieces in a board game’. And so it was at St Brigid’s. Grandpa Maurice, Jack Darcy, Joe, Alec and Pete Nehill and other pillars, including the ladies, all went to the same place each Sunday, took off their hats and put them under the seat in front (women kept theirs on of course) and any visitor who inadvertently took their place would have to move. The practice continues at my parish church in Northcote. An Irish gentleman who looks like he has come straight from milking occupies the same seat each Sunday, his two boys wedged in beside him. His chosen spot is just two rows from the back door. The moment Mass ends, he’s off. The problem with the custom was that if your pre-determined seat was vacant, people noticed you were missing and started to talk.

The altar boy who set himself on fire at Kirkstall reminds me that serving on the altar was a big deal. A few days ago – on 30 May, the International Day of the Potato – I had the great pleasure of another catch up with Brian Darcy. I asked Darc if he’d ever been an altar boy at South Purrumbete. ‘Yes’, he replied, ‘but only for one day’. Thinking he must have helped himself to the money on the plate, dropped the cruets or rung the bell at the wrong time, I said: ‘What in heaven’s name happened?’ ‘Well’, said Darc, ‘after Mass, the priest said to me ‘Brian, would you take this pile of News Weeklies and hand them out to everyone standing around outside’. (The News Weekly, I should remind you, was the anti-communist publication produced by Bob Santamaria). Off he went, innocent as the day is long, only to be spotted by his grandfather old Jack Darcy – a died-in-the-wool Labor Party man (and, to quote Darc, ‘a touch pig-headed’). His grandad stopped him, aghast, and told him to take the News Weeklies straight back to the PP. He did, only to have his services as an altar boy terminated on the spot. Though only a lad, and you’d think far removed in country Purrumbete from the centre of things, Darc can rightly claim to have had a direct and personal experience of the hottest, global issue of the time, communism v anti-communism.

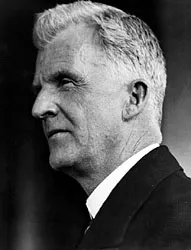

Old Jack, of course, was anything but a communist. But having known Jim Scullin, Australia’s Labor prime minister in the 1930s, Jack was a committed Labor man, something of a rarity in these parts. Scullin is somebody Irish Catholics should be proud of. He was the son of working-class Irish immigrants, spent much of his early life in Ballarat, was largely self-educated and was the first Catholic as well as the first Irish-Australian to serve as prime minister of Australia. His wife Sarah Maria McNamara, a Ballarat girl whose parents were also Irish immigrants, was an accomplished woman and also an active member of the Labor party. Their grave in the Catholic section of the Melbourne General Cemetery bears the following inscription: Justice and humanity demand interference whenever the weak are being crushed by the strong. A superb way to be remembered.

Many of the priests had direct Irish connections too and one or two had the Irish love of the horses. Fr Pat Maguire, much loved by the blokes, is remembered for telling the congregation at the start of one Mass: ‘This will be the shortest Mass ever. I’ve got a horse running in the first race in Warrnambool’.

Mass on Sundays is only one of many familiar Irish Catholic practices. There’s scapulars, stations of the cross, novenas, indulgences, holy cards, making a visit and so on. Annie tells me that when she was little every time her family set off to travel from Canberra to Sydney with a car load of kids, her mum would recite three Hail Marys and ask Our Lady of the Way and St Christopher to look after them. ‘Did you ever have a prang?’ I asked. ‘No’, she said. ‘Could it have been because your dad was a good driver?’….

But there is one very Catholic practice that is both so Irish and Catholic that it has to be mentioned: it’s the Rosary. You’ll be aware that our Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who is half-Irish, asked the new pope, Leo XIV, to bless his mum’s rosary beads in Rome recently. And what’s thought to have been my dad’s rosary has re-surfaced recently, in good condition, not the worse for wear you might say…. In Time of the Child, Niall Williams has a beautiful account of the bachelor Talty brothers reciting the rosary. The brothers remind me of Joe, Alex and Pete Nehill, regulars at St Brigid’s, eccentrics who achieved fame and the last laugh after bequeathing their farm, where they raised rare black pigs, to the National Trust. Williams describes the bachelor Talty brothers reciting the Rosary on their knees in the kitchen, heads bowed, ears sticking out like sprouting wings, and elbows on the seat of the chairs in front of them. The practice that was part-habit, part-ritual’, he writes, ‘dissolved time and space and through the rhythm of the spoken words made that kitchen other… Something elemental, open and raw’ was at work.

Ethnic Slurs

This prejudice accompanied many of our ancestors when they arrived from Ireland in the mid-19th c. They were depicted as illiterate, the wrong religious colour, a rough lot who were only capable of being servants and labourers. As the saying goes, they were as Irish as paddy’s pigs. The British press used the image of the Irish as pigs to portray them as agricultural, rustic, and indifferent to filth and squalor. The common term ‘paddy wagon’ is another put down. I heard it used on the ABC news a few nights ago. The term is said to have come from the US where it was used to describe a vehicle used by the many Irish who were police officers to arrest the many Irish who broke the law.

The truth is of course that, though stigmatised as ‘inferior’, most early Irish settlers made good against the odds and proved their critics badly wrong. Though unable to read or write, my great grandparents bought, cleared, fenced and ran a large farm and bequeathed it to my grandfather Maurice who was one of nature’s gentlemen. Irish communities funded and built beautiful churches and added great value to their new home in other ways.

My Walsh ancestors were of course as Catholic and Irish as paddy’s pigs. A Walsh clan legend even claims that, due to her lineage from the House of David which had a branch in Wales, the Virgin Mary herself was a Walsh and was popularly referred to as Máire Breathnach or Mary Walsh….

I don’t know about you, but my memory is that very little of our Irish heritage was explicitly passed down. Most likely I didn’t ask, maybe I wasn’t told.I have only sought to educate myself about it in recent years, including establishing where the original Walshs farmed and where they are buried. But when I think about it, I can see that when I was growing up there were a number of clues: My first name (Patrick). My surname (Walsh). My grandparents names (Maurice and Bridget). My Catholic upbringing. My sister’s name (Moya). The name of our church (St Brigid’s). The name of Grandpa Walsh’s farm just up the road (Glengariff, after a pretty bay in Ireland). Songs like Danny Boy and Galway Bay (‘If you ever go across the sea to Ireland’ which I only did in 2006 very near the closing of my day). Farming cows. A love of spuds and so on. But I don’t recall my family highlighting our Irish connections and roots. And though I’m pretty sure my great grandparents would have spoken Irish, I know of only one word of Irish that has been passed down: ‘cushla’, a beautiful word of endearment that means ‘beat of my heart’. I found it in a letter written by my dad’s mum, Bridget Moran, in which she addressed her daughter Maureen as ‘cushla’.

Why, like a lot of Italians, don’t I have dual citizenship? Why is Irish unknown to me, indeed a totally foreign language? Immigrants all over Melbourne use their native language but if someone at the Celtic Club on Sydney Road greeted me in Irish with Dia duit (jee-ah gwitch) and Conas ata tu? (kon-is ah-tah too). Hello,how are you?), I wouldn’t have the foggiest.

It turns out, however, that Irish was switched off pretty much everywhere, not just in my family, but also in Ireland itself. Until well into the 19th century, Irish was the majority language in Ireland when it became a minority language for the first time in its history. Several factors were responsible. One was the decision of the British to ban the teaching of Irish in 1831. Children were forbidden to speak it at school and were subject to corporal punishment if caught. A child who persisted in speaking Irish at school might be sent home with a tally board around his neck and instructions for the parents to make a mark on the board whenever the child said something in Irish. Each mark would earn an additional blow from the schoolmaster the following day.

But the biggest factor was the seven year Great Potato Famine (1845-1852). Not forgetting that it blighted part of Scotland too (where it is remembered as the Highland Potato Famine and forced many poor Scots to emigrate), the famine in Ireland wiped out the poorest communities where Irish was still spoken. A million died from hunger and a million left Ireland for the English-speaking world where Irish was useless. It’s also possible they were ashamed to speak Irish or pass it on. It came to be associated with poverty, death and failure while English represented success and a better future. It is all summed up powerfully in ‘Galway Bay’ which, as kids, we used to sing with gusto and feeling, though I doubt without realising what its author, the Irish doctor Arthur Colahan, really meant: ‘And the women in the uplands diggin’ praties/Speak a language that the English (which Bing Crosby changed to strangers) do not know/ For the strangers came and tried to teach us their way/ They scorned us just for being what we are’.

Irish only made a comeback after Ireland became independent from Britain. It is now enshrined in the Irish Constitution as the First Official Language and its teaching is compulsory through primary and secondary school. It has a long way to go and Unionists in Northern Ireland still object to installing street signs in both Irish and English. Meanwhile I was brought up inSouth Purrumbete in the 1940s singing God Save the King at school (I see his portrait is hanging on the wall behind me now), saluting the British flag, learning to write and read English, using coins that displayed the British monarch’s image, going nuts when the monarch visited, and basking in the glory of an uncle who fought for the British in World War II. In other words, my mind was totally colonised. I’ve only started de-colonising it in recent years.

Since we’re here for the Rabbie Burns Celtic Festival, let me start to wind up by asking two questions: (1) are the languages of Irish and Scottish Gaelic the same? And (2) Was Rabbie Burns known in Ireland? The answer to the first is that though Irish and Scottish Gaelic have a common origin in Old Irish, both are now distinct languages with different spelling, punctuation and grammar and mutually unintelligible. A Dubliner will not be understood if he uses Irish to order a whiskey in Glasgow. But Irish is given more priority in Ireland than Scottish Gaelic is in Scotland where English is the official language. And, unlike Scotland, Ireland is largely independent. Us Irish are well ahead of the Scots on those fronts!

What about Rabbie Burns and Ireland? He never went to Ireland (he died quite young) but he was known there especially in nationalist and literary circles. Burns advocated Scottish independence from Britain and admired the successful struggle of the colonies in America to break free from British rule and form the United States of America. He was a nationalist. This resonated with nationalist Irish.

Rabbie Burns was also known for his poetry in Ireland, thanks in part to Irish seasonal workers who returned to Ireland after stints in Scotland and could quote some of Burns best lines. No doubt his verses that poked fun at the puritan Presbyterians in Scotland went down well in Catholic Dublin, but he also wrote on universal themes that would soften the hardest heart anywhere. Who doesn’t know ‘Auld Lang Syne’, Rabbie’s hymn to friendship and farewell? And did you know that the custom of linking arms as ‘Auld Lang Syne’ is sung, which I recall from Carpendeit Hall in South Purrumbete days, is due to the Masons, whom Burns admired for their promotion of equality and brotherhood? So, if you’ve been wondering about including the Irish in a Burns Celtic Festival, its OK. I believe Burns himself would definitely have approved.

Let me finish where I began. I sometimes feel that the further we drift from our origins – geographically, historically, spiritually, politically – the more we risk becoming like chips of wood floating on the deep this way and that at the mercy of the tides and winds of cultural change. ‘Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold’, the great Irish poet William Butler Yeats once wrote. But I also think Jorge Bergoglio, our late Pope Francis, was onto something when he suggested that one way of finding our true North, to grow into our soul (or essence, what really makes us tick), is to reflect on our life, our history. Pope Francis once wrote: ‘Our life is the most precious ‘book’ that is given to us…. a book that unfortunately many do not read, or rather they do so too late, before dying. And yet, it is precisely in that book that one finds what one pointlessly seeks elsewhere’. I believe he’s got a point.Like Irish stew, we’re each made of bits and pieces but I hope I have said enough to stir your own memories and, if not done already, to get you to single out the Irish ingredient in you for further exploration, examination, critiquing and tasting.

Go raibh maith agat as teacht (guh-rev mo a-gut as tyacht).

Pat Walsh (alias Padraig Breathnach).

Pat Walsh is a former priest, educator, and international human rights advocate. He is now devoting his time to writing. His Walsh family history Mllking Our Memories: 150 Years of the Walshs of Walshs Rd, South Purrumbete is available on request <padiwalsh@gmail.com>

Amazing! Exactly correct in every detail. Except that for me St Brigid’s was really St James North Richmond. And so, there were no cows to milk or potatoes to be dug up. But there was James Scullin as the long-serving M.H.R. for Yarra. ‘That’s Scullin’s house’, my father would tell me as he pushed me along in my stroller.