Book Review by Frances Devlin-Glass

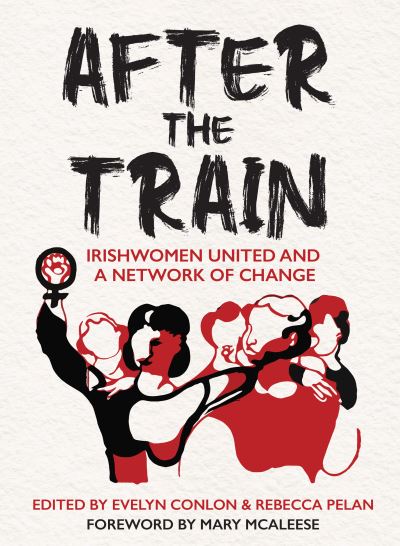

Evelyn Conlon & Rebecca Pelan (eds.): After the Train: Irishwomen United and a Network of Change, UCD Press, Dublin, 2025

RRP: €27

ISBN: 978-1-0685023-0-9

In the era in which Roe v Wade was walked back, the gains made by feminism, sadly, cannot be taken for granted. That is all the more reason for this book to be written and the history of feminism in Ireland to be documented by those who experienced first-hand a long and difficult fight against church and state for freedoms and equality for women. The editors are to be congratulated for assembling so many of these passionate voices, and for recognising that feminist activism has a long history in Ireland, much longer than second wave. Rebecca Pelan reminds the reader that it dates from early in the twentieth century and that the 1937 Irish Constitution which watered down the equal claims of women and children made in the Proclamation of the Republic in 1916 was vehemently contested by feminists at the time.

This is an invigorating history. What makes this book so irresistible is the range of voices of the twenty activists. And they are as urgent and committed in writing their individual accounts of what happened in the 1970s and later. Women from all classes and religious affiliations; women whose ideologies would be challenged radically, who are prepared to acknowledge their uncertainties and their forging of new ways of being and performing womanhood, politics, feminism. I had dealings with feminists in Ireland in the 1980s and ’90s because I was teaching new courses in Irish Literature and Feminism, but I clearly only touched the outer orbits of academic feminism, and was unaware of the depth and interconnectedness of the networks, so to read this retrospective is to become aware of the bewildering range of acronyms behind which they gathered. Indeed, if there is to be a second edition, and I hope there will be, it really would be helpful for non-Irish readers, at the risk of lengthening the document, to use full titles consistently. These were highly inflected: unionists who might also be socialists, but not necessarily; those mainly focussed on gay rights; those fighting for the rights of women to have control of their bodies (especially contraception and abortion); women in community publishing or mainstream publishing; women whose concerns were with equal pay. Naturally, if one is keen to liberate 51% of the population in an oppressive church-dominated state, the range of issues and topics for debate are legion. And spirited debate seems to have been the spirit of the age (as I remember it to have been in Australia in the ’60s and ’70s), and, significantly, transformative. They (we) were not going to live like their/our mothers.

If there was a mother-ship among the acronyms, it was probably Irishwomen United (is this why it’s not in the Index?) – such a powerful name with its resonances of 1798 and divisions to be healed. Many individuals’ names frequently criss-crossed these networks (I counted 36 acronyms and possibly missed some). The biographies at the end of each essay reveal how empowering this essentially grassroots activism was at the personal level, and how nation-building it was more generally for a secularising and modernising Irish state, in the five decades since the ‘Contraceptive Train’ (see below) media event. And how central feminism was in the fight against theocracy.

Since those heady late twentieth-century days, individuals have travelled and worked internationally and imported ideas from France, Australia and elsewhere; some have gone on to do higher degrees and to teach feminist theory and practice; some have become writers, poets and playwrights, and become esteemed members of Aosdána (Irish Academy of Artists), and run publishing houses; some have won esteem within the union movement and worked for equality of opportunity and wages; and some have set up and sustained non-directive counselling services for women and children in crisis.

This is also a book which testifies to the fun of these mind-bending years for individuals and groups. The stunts undertaken by nascent feminists are relished collectively: for example, the Contraceptive Train alluded to in the title of the book, was in effect an empty threat (but an effective one) as the women who openly imported condoms and ‘contraceptives’ from Northern Ireland, in fact secured only a handful and could rely on the ignorance of the Gardaí not to know the difference between aspirin and the real thing; Mary Doran’s innocent and hesitant attempt in response to the Boston Collective’s Our Bodies, Ourselves, to buy a disposable speculum to become familiar with her nether parts, and her routing by the pharmacist’s patronising, ‘for nose or ear?’) is one of many escapades recounted with joy; radical journalist Nell McCafferty’s chutzpah in coolly occupying the Federated Union of Employers boardroom and inviting the press to witness their interrogation of the EE directive on Equal Pay was another threat to the patriarchal order that lives in the memory of many of these women. There was clearly collective pride and pleasure in what these Irish feminists achieved by many different tactics. The invasion of the Forty Foot (a men only preserve at Sandymount) by women also testified to men’s sense of entitlement to exclusive use of a public space.

It’s also very interesting to observe the different methods used by women, and in particular, the humanity and selflessness of their actions. Empathy and non-judgmental engagement with suffering was paramount. If there was a perceived need, for example, to protect single mothers, or children adopted out, there were women very willing to volunteer and step up to do the job. Organisations like the Rape Crisis Centre or Cherish can’t have been easy to staff as rising living standards forced more and more Irish women into the paid workforce, but established they were because they were needed.

This book is a compelling read, and often a very moving and funny one. It should be compulsory for up and coming women who too easily lose sight of what their mothers and grandmothers achieved to make their lives fuller, richer and safer.

Frances Devlin-Glass

Frances is a member of the Tinteán editorial collective and a card-carrying feminist.