A Feature in two parts by Jules McCue

Jules lives and works on the unceded land of the Wadi Wadi People of the Dharawal Nation.

Part I: OVERVIEW

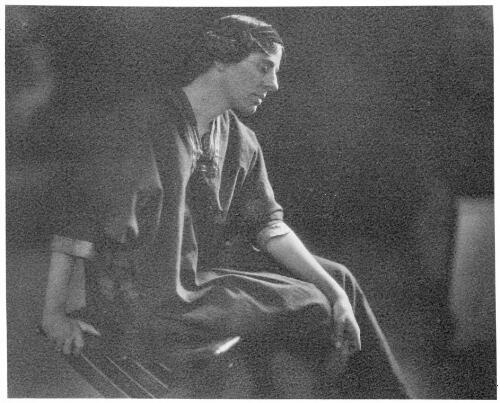

To some, Marion Mahony Mahony (1871-1961) may need no introduction or exposé. As the wife of Walter Burley Griffin, the designer of Australia’s federal capital, Canberra, she may be better known in Australia than in the United States where she was born, and probably less known in Ireland the birth country of her enigmatic father. In her own right, she was a pioneering architect and artist.

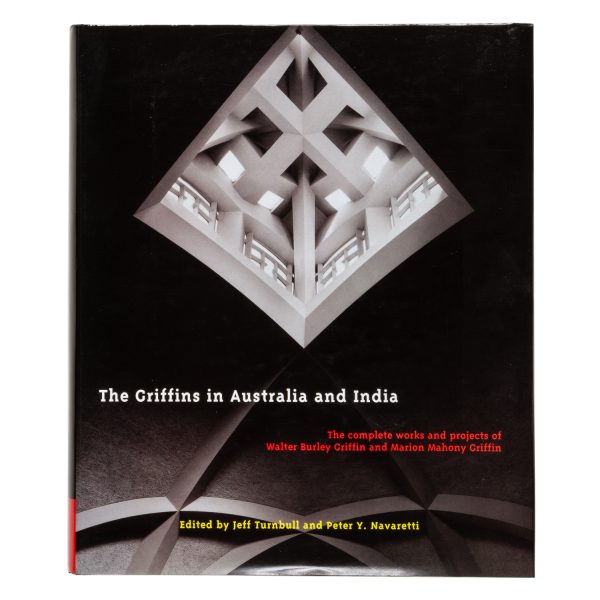

In 2021, the History Museum of New South Wales, Sydney, organised an exhibition and a film, entitled ‘Paradise on Earth’ to celebrate her work. Some of her drawings and other paraphernalia are held in museums in Illinois, New York, and the National Library of Australia in Canberra.

Elizabeth Birmingham’s ground-breaking essay on pioneering women architects documents her life and achievements. Marion Mahony was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1871, the year of the Great Fire. Her mother, Clara Perkins, was born in Illinois in 1841. Clara‘s parents were connected to the Mayflower Founding Fathers, the white elite of the American colonial state.

A TALENTED CORKONIAN FATHER

Marion’s father, Jeremiah Mahony born c.1843, was a more recent migrant from County Cork, Ireland. ‘Jere’ and family arrived in America between 1848 and 1858, probably fleeing the Famine in Ireland. They settled in Illinois where the Mahony sept from south-west Munster were plentiful. I have tried to establish ‘Jere’s’ exact place of birth and domicile in Ireland until he left as a child. Some information is recorded on his son’s and wife’s passport documents. However, the dates of arrival in America differ and no Irish town or Townland is given.

Jeremiah was a teacher, poet, editor, and journalist. At the risk of mobilising an Irish stereotype, it is said that he was a better teacher when drunk than most when sober (cited by Birmingham). One of his poems ‘A Teacher’s First Teacher’, year unknown, may allude to his Irish homeplace in the first verse. I am grateful to several people, Rory Bunce, Marie D’Arcy and Conor Nelligan from Cork County Council, Catherine Maher from Holy Cross Abbey, Thurles, Tipperary, and the Wexford poet in Missouri, Eamonn Wall who have assisted me in my search for his home. Marion has included some of his poems in her lengthy chronicles and manifestoes, The Magic of America, which detail hers and her husband’s, Walter Burley Griffin’s work and lives. Notably, she includes ‘Jeremiah Mahony in Ireland’ with the title of this eight-verse poem. This verse reads:

If knowledge is treasure so priceless, how grateful,

How heartily grateful to whom should we be –

Possessing a trifle or owing a pateful,

Who gave us its mystical alphabet key?

At the Cross of Clarine, does the school-house still nestle,

O’er its eaves do the ivy and jasmine twine,

With letters, by masterly Connor O’Brien?The poem reveals that in summer ‘the hedge made a line for our classes’ and that he who was versed in philosophy would flee from the ‘Cross if unable to explain a thing, be it Latin or geometry. In winter they sheltered in the O’Brien cottage where ‘peat sods’ made cushions and his wife, ‘gentle Alice’, was his only assistant. Another of Jeremiah’s poems included in Marion’s chronicles is ‘Legend of the Canyon’, in which he describes the Native American myth about how the Colorado River and canyon were formed. It resembles Australian Indigenous creation stories, summoning the ‘Great Spirit’ in which landscape and human life are intwined. Jeremiah‘s poem (The Magic of America, pp.81-2) evokes a sympathetic sentiment regarding the plight of the colonised:

. . .

Then the brave’s bold eye was darkened,

And his hand forgot the bow;

. . .

Dark his soul with sullen sadness

As their cavern depths below.

No doubt, Jeremiah Mahony was familiar with the culture and history of his own ancestral heritage. Perhaps he did not hail from Cork but sailed from Cork. Is this a mistake made by many, who assume the person came from the place of departure? Did Jeremiah Mahony really come from a townland of Clareen (An Cláirín) in Tipperary, living near the Holy Cross Abbey, or one of the many other Clareens in Munster? Or, as suggested by Marie D’Arcy at Cork City Council, does Clareen refer to the Irish word ‘cláirin’, the little board the students may have used to write on in the hedge schools? Is the Cross’ the punishing school regime and the Cross of Clareen an allegory for time and strife at school?

FAVOURABLE CONDITIONS AND MARION MAHONY’S CAREER

In her essay ‘Marion Mahony Griffin, Frank Lloyd Wright and the Oak Park Studio: The extraordinary career of a pioneering woman architect’, published in David Van Zantan’s (ed.) Marion Mahony Reconsidered (2011), Alice Friedman sets out three circumstances that make Marion such a compelling individual in the chauvinist world of Architecture and building. First, she identified as a professional architect, documenting this on her passport, believing her various talents were a creative gift to be used in work and life. Secondly, her marriage and working life with architect Walter Burley Griffin became her mission, wherein she chose ‘to support, promote and memorialise his contributions to the field of architecture.’ Thirdly, Friedman emphasises Marion’s independence of and eventual hatred for Frank Lloyd Wright, known to be the main player in the Prairie School of Architecture. These qualities possibly propelled her to pursue her own principles of architecture and life, as Marion, described by one commentator as Wright’s ‘best frenemy’, believed that he caused ‘irrevocable harm to the progressive, democratic, modern architecture’ [of America] (source: The Magic of America). Friedman notes that initially, Mahony’s ideals ‘complemented and overlapped with Wright’s well-known views on domestic and educational reform.’

There are several ‘favourable conditions’ in her young life resulting in her foregrounding not just a place for women in her field, but her brilliant innovations which for so long have been hidden in the silent History of Architecture. As happens in the Visual Arts world, much of her work was labelled as, or conveniently confused with, the work of her male collaborators, especially Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Burley Griffin, her ‘work husbands’ (see Claire Zilkey, ‘Meet Marion Mahony Griffin Frank Lloyd

Wright’s best frenemy’, June 8 2017).

Her supportive family and community were another of the significant ‘favourable

conditions’ that bolstered her career and principles. Her mother Clara Perkins Mahony was ‘ . . . herself a pioneer in public education and a lifelong leader in the campaign for women’s rights.’ Abraham Lincoln visited Clara’s childhood home. She also inherited her father’s intellect, humour, and creative mind, integral to her education, gifts, and talents. She says her mother’s family were Unitarians and her father was a Catholic: ‘the only two logical positions as father said.’(The Magic of America p. 130a). Both parents were open-minded and progressive, as an Irish Catholic of this time would usually cling to the enclave of Irish Catholic communities prevalent in North America, though Jeremiah from sectarian but pluralist Cork may have forsaken his religious roots for intellectual fervour and socio-political progress as were seemingly the basis for the happy marriage. The rationalist and inclusivist principles of the Unitarian aspect of Marion’s upbringing facilitated her spiritual and philosophical development; favouring her ideas on how to live and work. She had extensive support from several women who encouraged her career, financing her studies and later commissioning building designs. When tiny she was taken away from the burning city of Chicago. Later, as with her contemporary colleagues, the rebuilding became a fountain of opportunities made available for individual and collaborative innovation in architecture.

After the fires, the family moved to Hubbard Woods, Winnetka, on the shores of Lake Michigan where Marion and her siblings ran wild with nature. The five Mahony children were ‘safeguarded by a grand Irish housekeeper [sic Kitty Tully] and educated by that greatest of teachers – Mother Nature -and her loveliest mood’ (Magic of America, p.131). She describes the new home:

. . . in the loveliest spot you can imagine, beyond suburbia – four houses and no others within a mile in any direction. Our home was at the head of a lovely ravine.’ (Magic of America, pp.130a-131)

Such a childhood developed in her, a deep understanding of natural environments, their importance to the earth’s and therefore human survival and to a child’s education. Education was important to her holistic philosophy of life.

In 1882 her father seems to have died from an overdose of Laudanum prescribed for a nervous condition. She says that he was adored by the community and he would stay up till 2am discussing ideas and writing poetry with a neighbour. He was a much-loved Chicago school principal and upon his death, a large sum of money was collected at the school for his family. She stresses that ‘Father was one who acted on conviction of the human individual’s power,’ highly supportive of his staff and that . . . ‘Father had the reputation of being the best slinger of the King’s English in the city. And friends have told me how he would sit quietly and then suddenly take the floor and the whole group would be aflame. Oh those Irish!’, says Marion (Magic of America, p.137).

Later in Sydney, she and her husband would become familiar with Rudolf Steiner’s ‘Anthroposophy’ movement. They both embraced his ideas, merging the mystical/spiritual with intelligent and scientific striving for knowledge. Her ideas were shaped by her Unitarian community background, combined with her inquiring mind and observance of Steiner’s principles in which the arts and science were of underlying importance in the education of the young. She explains that ‘I have good reason to thank Aunt Myra for her continued interest in my musical education . . . [it]enabled me . . . to practise Beethoven and other composers with sufficient satisfaction to myself to be a great and lasting healing of the soul’ (The Magic of America p. 146). She writes about these principles and political views at length in her chronicles.

This biography/evaluation of Marion Mahony Griffin’s life and work continues next month in Tinteán. A list of sources will be available then.

Jules McCue

Jules McCue is an artist, musician, writer and independent researcher. Some past essays include Extraordinary Exhibition: Holy Threads: textile art of Sanvandhary Vongpoothong [1998], ; Black Man in a Whiteman’s World: Indigenous Art in NSW Jails [1998] ; From Cork to Coalcliffe: Finding Richard Coady [2017 ; Review of a monograph St Manchan’s Shrine, [2023] and The Poetry of Trans-Atlantic Eamonn Wall: part of the ‘river of years’ of Irish poetry [2023]. Master of Creative Arts dissertation: 1. Wildflowers and White Porcelain and 2. Circles and Seeds: the history of women artists through Still Life Painting [1993-4].

Conference Papers: Not Surrealism, Magical Realism [1995] ; Katheen and Kitty: Two Women; a painter and a composer and pianist, both brilliant, both of Irish heritage [2019] ; Historical Ireland: control and catastrophe through stories of circumjacent mythology, weird and wonderful, ambiguous shapings of the vigorous mind [2021]; Dissident Donegal: They keep leaving, [2024]. www.julesmccue.com