An Address on 27 June 2024 to the Celtic Club at the Wild Geese Hotel, Brunswick

By Dr Val Noone

SUMMARY:

Drawing on personal experience and research, this talk offers six snapshots from the 190 years of the Irish and their descendants who settled in Melbourne on the lands of the Kulin nation. Short overviews are offered of settler and Indigenous histories, followed by stories about Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, my great-grandfather John Noone, Archbishop Daniel Mannix, and Uncle Wayne Atkinson.

Introduction: remembering Colin Bourke

Is honór dom é a bheith anseo inniu. Admhaímid muintir Woirworung agus muintir Bunurong, muintireacha bunducasaigh den áit seo, le meas mór ar na seanáoirí. We meet on Wurundjeri land of the Kulin nation, which land has never been ceded. We pay our respects to elders past, present and emerging.

I wish to pay particular respect to Professor Eleanor Bourke, Wergaia and Wamba Wamba elder, and chairperson of the Yoorrook Justice Commission which is conducting the first formal hearings into the injustices suffered by Aboriginal people in Victoria.

In 1996 I was privileged to meet her at University College Dublin when she and her late husband Colin took part in the conference on Australian identity organised by David Day. Colin’s mother was a proud Gamilaroi woman from New South Wales and his father was an Irish Australian. Colin was born in Sunshine and later became the first director of Aboriginal research at Monash University.

You will remember that a few years ago Andrew Bolt attacked people of mixed Aboriginal and European parentage as not being real Aborigines, and he was found guilty of racial discrimination. In Dublin, three decades ago, Colin Bourke delivered a keynote speech about contemporary Aboriginal identity, in which he emphasised how Aboriginal people of mixed parentage retain ‘a common philosophical and historical bond which makes [them] one people’. Colin’s remarks are relevant today.

Historians such as Anne McGrath, Elizabeth Malcolm and Dianne Hall have written stimulating surveys of attitudes among Irish Australians towards the Indigenous peoples. An excellent documentary on the matter, Dubh in a Gheal/ Assimilation, directed by Paula Kehoe and narrated by Louis de Paor, is the best account I know of. One memorable line came from Garry Foley, the veteran Aboriginal campaigner. ‘Is Foley an Aboriginal name then, Garry? asked de Paor. Foley replied that the Foley was way back in his line but his mother was a Doyle.

There is much to be said on our topic and today I am offering just snapshots.

1. The Irish in Victoria 1835-2024

Snapshot 1: a rapid reminder of 190 years of the Irish in Victoria. From 1835 on, John Batman and John Pascoe Fawkner led groups of Europeans from Tasmania to pasture their sheep, grow crops and build a town on the Kulin lands of Port Phillip Bay. Partly by negotiation but largely by force, these early European settlers carried out what historian Richard Broome has described as ‘one of the fastest land occupations in the history of empires’.

The Irish were among them. Batman’s wife, for instance, was Eliza Callaghan from Clare, whose life story, indeed, has a tragic ending. Next came British government and squatter-financed bounty immigrants. Then, following the Famine, gold-rush immigrants came in tens of thousands. Clare turned out to be the county with the highest percentage in Victoria.

The years from 1850 to 1900 were the years of the biggest Irish migration to Victoria. The Irish-born population peaked, it seems, at 228,000 in 1891. The Anglo-Irish supplied key officials in the running of the colony while most of the Irish came as labourers and domestic servants, some three-quarters of whom were Catholics. A good half of the Irish who came spoke the Irish language.

Throughout most of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, there was one important difference between the Irish and all other ethnic groups of immigrants to Australia: women formed a majority or near majority at an early date.

Having left Ireland because of bleak prospects, the settlers sought a better life and had a thirst for land. In due course, many families prospered. They and their descendants have figured in most aspects of Victoria’s history.

Migration continued at a much slower rate until today, with a bulge in numbers in the 1950s during the largest twentieth-century outflow from Ireland, and with a new generation which includes not only immigrants but, these days, highly qualified international itinerant workers. Today, around two million Victorians have Irish ancestors.

By the way, there is an opening for the Celtic Club to host a session on the Irish in Brunswick. If they do, I have a few suggestions about Bella Guerin, John Curtin and others, as well as the Sarah Sands successful 1890s defence of Irish rights.

2. Sample of Kulin history 1835-2024

Snapshot 2: a sample beginner’s knowledge of Kulin history. For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal history has been oral. Now in 2024 there is also abundant Aboriginal history in books and online. Rachel Perkins’ 2022 television series Australian Wars showcased a new generation of Aboriginal historians.

The Kulin nation is made up of Woiworung, Boonurrong, Wathaurong, Taungurong, and Dja Dja Wurrung peoples. Their stories highlight such things as:

- Melbourne is built on the lands of two language groups, the Woiworung and the Boonurong, who are part of the Kulin nation;

- before Melbourne was founded in 1835 at least 11,500 Aboriginal people lived in Victoria in some 30 language-culture groups;

- less than 30 years after 1835 so many Aboriginal people had been killed by frontier violence and European diseases that only about 2000 survived;

- in the 1850s the government moved Aboriginal people to reserves such as Coranderrk near Healesville, and later Cummeragunja on the New South Wales side of the Murray, Dhungalla in Yorta Yorta language;

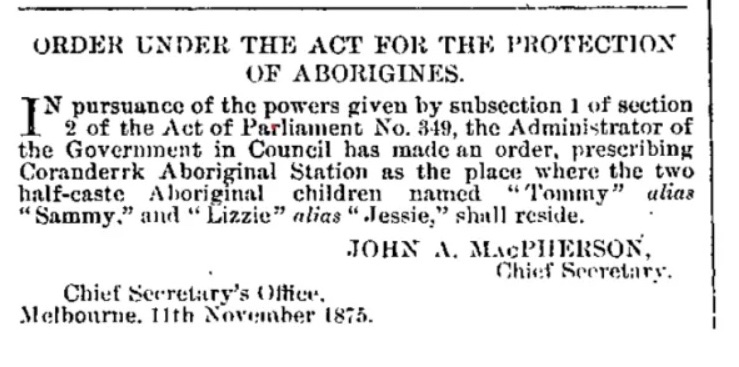

- the 1886 Victorian government’s Aborigines Protection Act, known now as the Absorption Act and formerly known by the offensive race-based name of ‘the Half-caste Act’: this allowed the removal of mixed race children and created what is known as the Stolen Generations;

- the strong 1930s Aboriginal political campaign for rights;

- the successful 1967 referendum to include Aboriginal people in the census;

- the 1980s royal commission on Deaths in Custody;

- the present-day surge in Aboriginal cultural revival;

- the unsuccessful 2023 referendum on the Voice to Parliament;

- the setting up of the Yoorook Justice Commission, the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria, and the preparation for negotiating a Treaty.

- the Commission has summarised the story: ‘First Peoples have been caring for Country for thousands of generations. The history of Europeans coming to Victoria 200 years ago and taking First Peoples’ land is one of wrongdoing and devastating loss. But it is also a story of First Peoples’ resistance, survival and ongoing connection to country.’

3. 1859: Charles Gavan Duffy’s noble moment

Snapshot 3 is more specific: on Monday 7 March 1859 a deputation of five Aborigines came to Charles Gavan Duffy, the minister for land, at his office in Latrobe Street, to ask for a piece of land on the Acheron River, they called it Nak-krom, between the Goulburn River and the Great Dividing Range, near Cathedral Mountain.

Ulster-born Duffy, then 42, had been in Melbourne three years. A key figure in the Young Ireland movement, he was tried for treason felony four times but got off. In 1855 Duffy and his wife Susan and children migrated to Melbourne. They were living in Hepburn Street, Hawthorn.

The members of the delegation were five traditional owners, Taungurong men from the upper Goulburn, members of the Kulin nation: Bearinga, Murran Murran, Pargnegean, Kooyan and Burrupin. The Argus reported that they were all tall and seated themselves ‘with an air of grave courtesy’. The deputation asked for ‘a tract of land in their country set apart for their sole use, occupation and benefit’.

Duffy ruled in favour of the Aboriginal application and granted them the land, subject to there being no local difficulties. However, within a year, thanks to local squatters, the claim was derailed. Duffy did not follow through on the Acheron land claim.

4. John Noone: mapping Kulin lands

at the Lands Department showing

the selection map for the Parish

of Goorambat, County of Moira,

northwest of Benalla,

10 September 1874

Snapshot 4. If you have looked up maps to trace ancestors who selected land in Victoria, you may have found at the bottom right-hand corner the name of John Noone, my Galway-born great-grandfather. See handout. From 1861 to 1888 John was the photo-lithographer at the Department of Lands and Survey. Photo-lithography is the skill of turning images such as maps and paintings into photographs and then into stone images suitable for printing. John was a member of the team which put a British colonial grid over the Kulin lands. Those of us whose ancestors played a part in the dispossession of Aboriginal Australia have a responsibility to work for reconciliation and land rights today.

5. Daniel Mannix for reparation

Snapshot 5: Catholic Archbishop Daniel Mannix’s strong defence of Aboriginal rights. David Moloney has collected a list of quotes from the 1920s through to the 1950s.

During the Caledon Bay Crisis of 1932 to 1934 the Yolgnu people of the Northern Territory, acting according to their laws, killed five Japanese fishermen, a policeman and two white men. Mannix supported those opposing a punitive expedition against them. In April 1934, when Yolgnu man Dharkiyarr was sentenced to death for the murder of the policeman, Mannix made headlines when he opposed the imposition of European law on Dharkiyarr as ‘a travesty of justice’, and called for special laws for Aborigines. Dharkiyarr got off but disappeared soon after.

In 1938 when the great William Cooper organised an Aboriginal Day of Mourning for the 150th anniversary of British settlement, Mannix supported him but said Australia should go further and organise a day of reparation. In 1941 Mannix summed up his opinion: ‘White people in Australia had committed the original sin against the Aborigines … [and] it had not yet been blotted out.’ Compensation was needed, he said.

In 1946 when the Australian government was planning to allow Britain to test nuclear weapons in the Kimberleys, Mannix said: ‘If atomic bomb experiments are carried out in the Kimberley areas much harm will result to the Aborigines.’

Mannix’s comments were mostly made at the annual fete at Kew to raise money for the Pallottine Fathers’ mission in the Kimberley. Mannix does not seem to have introduced policies relating to Aboriginal people in his Melbourne diocese.

6. On country with Wayne Atkinson

Snapshot 6. Last year a small group revisited the Charles Gavan Duffy land grant issue. On 26 January, Invasion Day, senior Yorta Yorta elder Wayne Atkinson generously guided two visiting Irish historians and myself past Healesville and over the Black Spur to Cathedral Mountain where the land was granted. The historian Peter Gray was in Melbourne researching Gavan Duffy and was accompanied by his partner and fellow historian Emily Mark-Fitzgerald.

Uncle Wayne traced some Taungurong history and discussed the implications of the 1859 grant by Duffy. He says that this was the first successful Indigenous land rights claim in Australia, but it failed.

Wayne, a retired senior lecturer and senior fellow in political science at the University of Melbourne, explained his research into the history of Aboriginal reserves. Wayne has shown that similar laws against First Peoples were used by: a) Oliver Cromwell in the 1652 Act of Settlement to sanction the dispossession and removal of the Irish “to Hell or Connaught”; b) the United States Indian Removal Act of the 1830s which brutally displaced Native Americans on to reserves, west of the Mississippi; and c) the 1886 Aboriginal Protection Act of the Victorian government.

At the time Peter Gray was finishing a book on William Sharman Crawford, a Protestant landlord from County Down, who had worked with Gavan Duffy in Ireland on land issues. Emily is the author of a large book about monuments to the Irish Famine throughout the world and had just co-edited a book on the Famine in Dublin. Wayne has long been well-informed and sympathetic about the Famine and Irish history. The craic was great.

Conclusion: work needed, a 1998 feat

The relationship of Irish immigrants and their descendants with Indigenous Australians demands a lot more work on each era, especially on the land issue. For example, in the 1880s, when Irish-Australians joined the tens of thousands selecting land in Victoria, and sent back extraordinary financial support for the Land League in Ireland, some ignored the land rights of the Kulin, but some, in vain, opposed the 1886 Aborigines Protection Act and the closing of Coranderrk. Who saw or spoke about the contradictions involved? As far as I know, nobody has researched the details of responses by activists such as Joseph Winter, Michael McDonald and Peter Jageurs and visitors such as the Redmond brothers and the Walshe sisters. On another occasion, one could examine the role of Irish-born members of the Victorian parliament, John O’Shanassy, John Gavan Duffy, Bryan O’Loghlen, and George Higginbotham.

Coming to the present day, an achievement of which a good number of you were part, deserves a mention, namely the putting up of the Famine Rock at Williamstown in 1998. I was fortunate to chair the committee. At the unveiling, Victor Briggs, representing the Bunurong people, gave the Welcome to Country. He was most generous in his sympathetic speech about the Famine and the orphan girls. Emily Mark-Fitzgerald, in her study of Irish Famine monuments worldwide, which I have just mentioned, noted that the Melbourne monument pays tribute to the Aboriginal people, whereas most Famine monuments avoid awkward aspects, such as the role played by Irish immigrants in British colonisation.

This talk has only touched the surface concerning Irish-Aboriginal relations in Melbourne. I have offered six snapshots: a brief overview of the history of both Irish immigrants and Kulin peoples; and also four episodes – Charles Gavan Duffy’s noble moment and subsequent failure to follow through; John Noone’s role in mapping the Kulin lands; Daniel Mannix’s strong position on dispossession and the need for compensation; and Wayne Atkinson’s dialogue with Irish historians on the basis of continuity between Cromwell’s policies and Victorian government ones. Go raibh maith agaibh. Ω

_________________________

Dr Val Noone is the author of Hidden Ireland and Victoria and a co-author of Gaeilge Ghriandóite: A go Z a hAon. He is a Fellow of the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne. In 2013 the National University of Ireland awarded him the degree of Doctor of Literature for his contribution to Irish Studies in Australia.