Book Reviews by Frank O’Shea

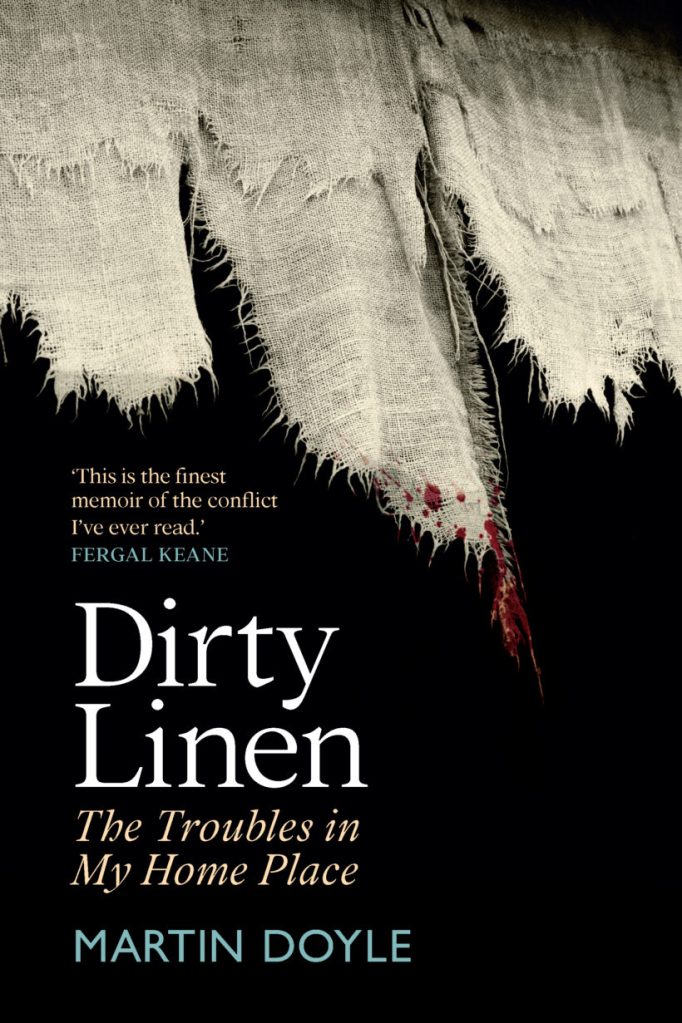

DIRTY LINEN. The Troubles in My Home Place. By Martin Doyle. Merrion Press 2023. 339 pp. €21.99

The main reaction to a book like this is to marvel that anyone who could have left the place decided to remain in Northern Ireland in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Reading it is a reminder to those like this reviewer who lived in the South during many of the early years of The Troubles, a reminder that we heard so little or closed our ears to the atrocities being carried out by both sides. ‘A veil of silence has been drawn over the horrors of the past,’ the writer says, ‘its terrors left unprocessed, details forgotten, killings happening so thick and fast that the dead were not properly immortalised.’

In a sense, the book is the author’s attempt to remember those days and the effects that they had on the ordinary working-class citizens of part of a country that preaches to the world about rights and responsibilities. The examples the author gives of people who were murdered by the UVF/UDA on one side and by the IRA/INLA on the other, take up most of the work. As a journalist half a century later he interviews the children and grandchildren of those victims, gets their stories, tries to work out how they survived.

A few of the chapters tell the story of his own childhood and school years in a school where, as a Catholic he was in the minority, and the bullying he had to put up with. The teachers were either uncaring or, in more than one instance, part of the problem. And this was an elite post-eleven-plus grammar school, the source of the future leaders of the statelet.

Most of the incidents covered in the book took place in the region of Banbridge in Co Down. In the South, the particular incident in that area that would raise most hackles was the slaughter of the Miami Showband on their late-night return from a performance, but there are other equally awful incidents, the perpetrators as likely to be from one side as the other. ‘Roughly half of Troubles deaths are attributed to Republicans, 40 per cent to Loyalists and 10 per cent to the British state,’ he writes.

In the case of the Miami murders, ‘at least five UDR men were involved,’ he says. Do we need to remind ourselves that these were paid officers of the Crown? He claims that in this case and in many of the others he covers, the name of Robin Jackson comes up, responsible he says for some 50 killings. He was ‘untouchable because he was an RUC Special Branch agent.’ He died in 1998 without ever having spent time in prison.

The author, Martin Doyle, is Books Editor of The Irish Times with a lifetime of journalism in Britain and Ireland. His background was working class, but as he says, ‘In our low-level civil war, sectarian trumped proletarian; belligerents on both sides were largely drawn from the working class, divided by a common rung.’ Reading it, you need to remind yourself constantly that this is not some distant -khan or African kingdom, but this is Ireland.

If you ever thought how wonderful it would be if the country was united, this book may change your mind: why would anyone ever want to have anything to do with the kind of people described here? This is not the fault of the writer, who is objective and factual at all times and keeps well away from easy condemnation. The heroes of his book are the survivors, adults who half a century ago, lost their father or mother or sibling, and to the admiration of the reader, have managed to reach calm maturity.

Perhaps, we do need to learn from these survivors, to befriend them, to forget the awfulness they have had to endure. Maybe the people in Cork and Laois and Meath would after all benefit for knowing those people.

Martin Doyle has done all of Ireland a favour.

THE LONG GAME. Inside Sinn Féin. By Aoife Moore. Penguin 2023. 321 pp. €15.99

As things look now, Mary Lou McDonald will be Ireland’s next Taoiseach. Her party, Sinn Féin, has consistently had figures above 30 per cent in recent polling and fully expects to be running the Republic of Ireland after the next election. Very likely it would need to be a coalition arrangement and it is difficult to see either of the traditional parties Fianna Fáil or Fianna Gael being part of that union. The question that many people must feel like asking is how a party which began as the IRA, whose members were on the hunger strike and were involved in kidnappings and killings, could achieve such sudden respectability.

Aoife Moore is from a nationalist family in Derry, but is first and foremost a journalist, someone who asks awkward questions. Initially, Sinn Féin agreed to interviews for the book, but withdrew when they realised that some of their answers might trouble voters. Many of her sources for what she writes are people who left the party or no longer worked for senior people in the party. A number of chapters are devoted to the many rounds of decommissioning leading up to the Good Friday Agreement.

What is perfectly clear from reading the book is that Sinn Féin was originally run by current or former members of the IRA. She gives a number of examples of SF meetings of today, called to discuss some social or political issue. As the meeting starts, known local IRA men come in to sit in a group at the back of the hall and listen carefully but say nothing. The meaning of their presence would be clear to those involved in the discussions. ‘In reality, Sinn Féin is a radically top-down party. It is unheard of for a policy change to be driven by the grass roots,’ she writes.

The central character in the book is Gerry Adams. He says that he was not a member of the IRA, but no one believes him. The author gives many examples where his decision on some matter is final and expected to be supported by the party. It was accepted by Sinn Féin that in any matter, his word, his opinion was final. When it came to his time to retire, now a Dáil deputy for Louth, he let it be known that his successor was to be Mary Lou McDonald.

Adams comes badly out of the case of his brother Liam who was a sexual abuser (as indeed their father was also). Gerry was told by the victim of the abuse, but at no stage did he pass that information to the police. The book covers the affair in some detail and Adams comes off poorly as he does in the case of MáirÍa Cahill, also the subject of sexual abuse by a former IRA man, who provides her own account in the book below. Sinn Féin had great difficulty weasling their way out of those incidents when they became more widely known. And, for those who remember, there still is the question of what happened to Jean McConville.

When Sinn Féin MPs at Stormont are paid, their salary goes straight to Sinn Féin coffers. They are then given the NI minimum wage by the party; it is not entirely clear whether the same applies in the South of Ireland for elected TDs.

This is in many ways a disturbing book. Even granted that it is now half a century since the IRA were killing people, it is still difficult to get away from the thought that those who followed in their beliefs and philosophy are now a political party with successes in local elections in the North and general elections in the South, each preparing for government on the relevant side of the Border.

ROUGH BEAST. By Máiría Cahill. Head of Zeus 2023. 447 pp. €15.44

Máiría Cahill is grand-niece of Joe Cahill, one of the founders of the Provisional IRA. Although her parents are not involved, her wider family are long-time Republicans in Belfast and Northern Ireland. At the age of 16, she was raped by a man named Martin Morris, an abuse that continued for some months. He was a member of the IRA’s Civil Administration Unit, a group that replaced the police in republican areas and were involved in actions like kneecapping and beating of young offenders. This is not a work of fiction.

It took some time for Máiría to speak with some of her friends about the abuse. When the IRA were informed, they set up a kind of kangaroo court, involving at first meetings with her where she gave an account of what happened, an account that she admits was incomplete for the obvious reason that she did not like to speak about it. This all happened in the years around the turn of the century. Some ten or so years later, Morris and the people involved in the IRA investigation were brought to court. The book spends a lot of pages describing the events leading up to that trial and the actual trial itself, but in truth it is difficult to follow what was happening, apart from the fact that no one was found guilty.

The second half of the book is devoted to the author’s long disputes with Sinn Féin, first with Gerry Adams and towards the end with Mary Lou McDonald. It is a long and at times narrowly-focused diatribe against SF, who found themselves trying to put up some explanation of how a girl of 16 could by abused by an IRA veteran and would have to face, in the course of the investigation by that body, her abuser who was denying everything.

The book is so long and technical that in truth, towards the end, the reader begins to feel sympathy for Sinn Féin. You have to keep reminding yourself that this is a woman who, as a teenager, went through the most appalling violation and that the subject of her attacks are people who have responsibility for the deaths of many people. And you might remember also that Sinn Féin may well form the next government of Ireland.

Well written, but longwinded.