by Dymphna Lonergan

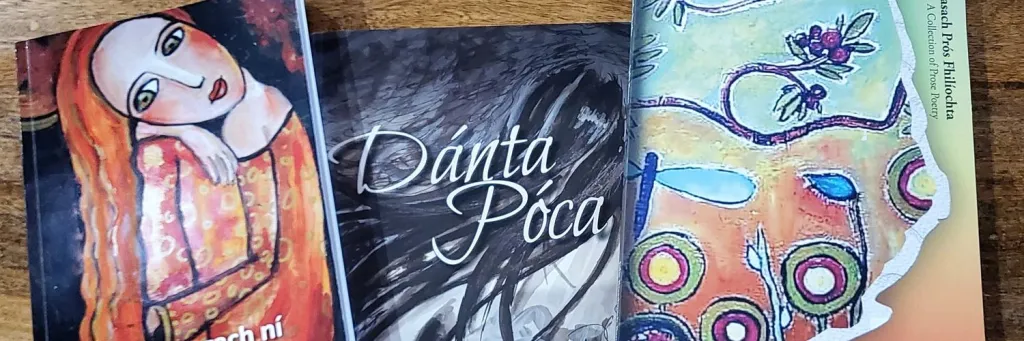

Conamara born and bred and now an Australian resident, Julie Breathnach-Banwait has made her mark in writing Irish language poetry for such Irish publications as Aneas, Comhar, Feasta, and The Galway Review. In Australia, her poetry has appeared in An Lúibín, The Journal of the Australian Irish Heritage Association, and our own Tinteán reviewed her poetry collections Dánta Póca (2020) and Ar Thóir Gach Ní (2022).

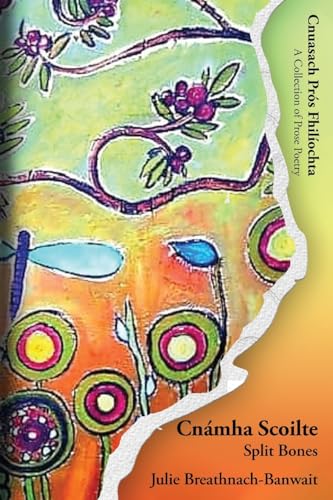

Now this prolific poet has brought to us a brave and bold new world of bilingual prose poetry in Cnámha Scoilte Split Bones published by Bobtail Books (2023). Breathnach-Banwait’s hyphenated surname represents a duality in this poet: made in Ireland, and in Irish language Ireland especially, but grown and honed in her twenty odd years travelling the world. Many immigrants to Australia live a similar duality, a ‘past country’ core that is central to the Australian experience. Cnámha Scoilte Split Bones reveals this duality in moments of memory captured in time and language, Irish and English side by side. Her opening to this prose poetry collection is a poem that begins:

Canann an t-éan seo This bird sings

dhá phort two tunes

an chéad canta the first sung

sílte mar mil dripped honey-like

trí theanga rúnda through secret tongues

In this prose poetry collection of 51 pieces, Breathnach-Banwait’s bilingualism brings a richness to our reading. She takes us from Conamara to Australia, via North Macedonia, China, and New Zealand, snapshots of humanity and nature both observed and responded to.

Prose poetry offers freedom from structure, from line markings, while retaining rhythm, imagery and emotional layering. Bilingual prose poetry reveals yet another dimension: word choice that can challenge and provoke. That can make you question your assumptions as you read and reread.

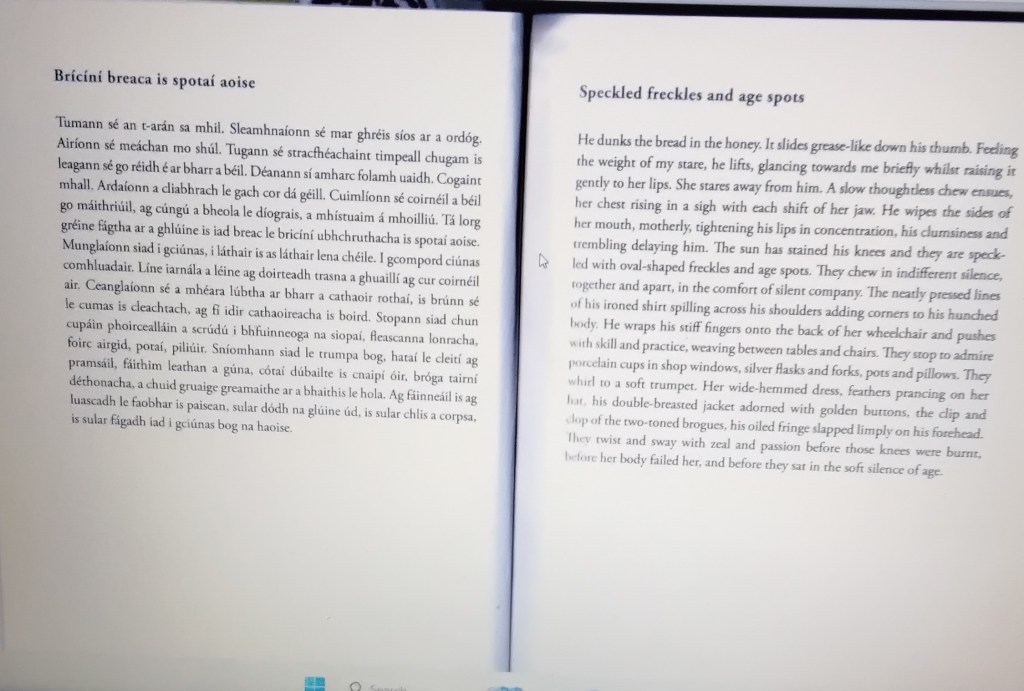

Above is an image from the bilingual prose poem ‘Bricíní breaca is spotaí aoise Speckled freckles and age spots.’ Around line five, the Irish reads ‘Tá lorg gréine fághta ar a ghlúine is iad breac le bricíní ubhchruthacha is spotaí aoise’ with the meaning that the sun has left its mark on the man’s knees in the form of age spots. However, the poet has chosen the verb ‘stain’, a stronger word choice than expected: ‘The sun has stained his knees and they are spotted with oval shaped freckles and age spots.’ On consideration, however, the word ‘stain, that can carry negative connotations, is a reminder that signs of ageing are not usually seen in a positive light.

This prose poem is Breathnach-Banwait at her best. She invites us into a scene that appears at first as mundane, a man dunking bread in honey, but slowly expands our view to two people, two elderly people, one who is disabled. It is a poignant scene, and we are beguiled with arresting imagery: Líne iarnála a léine ag doirteadh trasna a ghuallí ag cur coirnéal air. The ironed shirt giving the impression of how his body once looked- putting a corner on him is how the Irish translates. On leaving the cafe, they pass a window full of bric a brack calling to mind their youthful selves when they were upright and proud, perhaps at a dance where they met: sular fágadh iad i gciúnas bog na haoise/’and before they sat in the soft silence of age.’ Here we are also reminded of Seán Ó Riordán’s poem ‘Çúl an Tí, where a jumble of items takes on greater significance.

While it is an added advantage to be able to read the Irish language version of these prose poems, and there is much enjoyment to be had from contemplating both versions, Cnámha Scoilte Split Bones is for all lovers of fine lyrical poetry and prose poetry who relish in how the ordinary can be made extraordinary.

With a striking cover design by Aoife Dowd from Carna, Galway, Cnámha Scoilte/Split Bones is available from Bobtail Books https://bobtailbooks.com.au/