Book Review by Frances Devlin-Glass

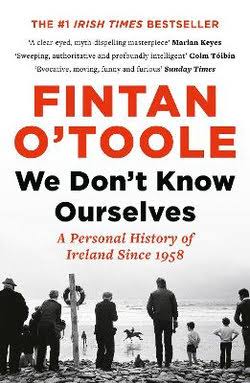

Fintan O’Toole: We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Ireland since 1958, Head of Zeus, London, 2021

RRP: $24.99

ISBN: 9781784978341

My esteemed colleague, a voracious consumer of books, Frank O’Shea, reviewed Fintan O’Toole’s social history in 2022, and there was much in the book that probably would not have raised his eyebrows, because he knew the scene as an Irish-born reader. But it did raise mine often, and over and over, so I thought a second look from the diasporic margins might be a useful Tinteán addition.

The time to write this extraordinary book was gifted to O’Toole during Covid 19. He’s undoubtedly better connected to archives of all sorts than most, and deeply immured in the day-to-day of Irish politics, so it’s a rich compilation of self-contained essays, really, one for each year of his life with a few longer stretches of years punctuating the rhythm, starting with a clear-eyed assessment of the urbane Gay Byrne’s ‘central place in Irish life’ on the Late Late Show and the way his ‘calm, seductive and passionless’ tone exposed previously unspoken intimacies – a young woman’s dilemma about being pregnant and her thoughts of leaving the child in a brown paper bag in a toilet; his revelatory ‘I have never…told this to anyone in my life’ stories; his provocative interviews with a lesbian nun, or a man, apparently ‘the only such man in Ireland’, talking about ‘what it was like to be homosexual’. O’Toole talks of the paradox of talking of sexuality and being at the same time a ‘good Catholic’ and a political conservative. What overrode all was his capacity to generate entertainment out of ‘inarticulacy, embarrassment and evasiveness’.

It’s a very ambitious work whereby a little detail, for example, the arrival of the first escalator in Dublin (in a Roches’ store in 1963 where the excited customers might ‘[levitate] like fakirs’) might widen out to a discussion of modernity, bright and shiny, and embodied in another new arrival that year, the alluring and sophisticated J. F. Kennedy. At a Garden Party for him at Áras an Uachtaráin, the frail but revered and ineffectual Eamon de Valera could not prevent mass hysteria and his American guest from being treated like a Beatle. By comparison with JFK, Dev appeared a tired, old-fashioned, uninspiring leader (of a state which was haemorrhaging people to countries like the USA).

O’Toole’s eye unfailingly goes to the quirkily revealing: who knew Crumlin gets a mention in Shakespeare, or that the housing estate built there in the 1930s and 1940s to accommodate those moved out of the Liberties was designed to replicate on a larger scale the badge developed to advertise the Eucharistic Congress of 1932 modelled on the Cross of Cong, and ‘the magic of Celticism and Catholicism’. People used to overcrowded tenements found themselves in this new development ‘all Sinn Feíners, all for themselves alone,’ but the compensation was ‘water running into the big Belfast sink in the kitchen, into the bath, through the cistern of the lavatory’, another flow of modernity.

For the marginal outsider like myself, this book explained the geopolitical realignments that occurred so quickly and unexpectedly in Ireland between 1958 and 2018. He sees the roots of the malaise that beset the Church, for example, as being the arrival of TV in Ireland, and the consequent primacy entertainment gained over Church authority. That’s a simplistic one-factor analysis, but in subsequent chapters, he fills out the slow erosion of authority with the spread of education, the rise of feminism, and of course, the role the Church took in its own undoing. The early part of the book focusses on the impact of modern mass media and how the world began to infiltrate a very parochial country with little exposure to outside influences during the first few decades of the Free State. The early Free State was also ideologically opposed to the United Kingdom, and so looking for its music and tv elsewhere, and after an unedifying flirtation with Cathode Ni Houlihan (and her premodern ‘dreamtime’ in the west of Ireland), found its ‘dreamworld’ in US TV, and especially in Wild West narratives. Anything to avoid becoming a subaltern of the BBC. Another fascinating transformation was going on in the dance halls where ceilidhs gave way to Big Bands and US-inspired Country music before succumbing to Beatlemania (emanating from a hated UK) in the 1960s and 1970s.

Although when interviewed, O’Toole claims he didn’t have material to hand for an autobiography or a memoir, some of the most memorable sections of this social history are personal. The account of him aged twelve letting a pig loose on a farm in 1970 where he’d gone to learn Irish in a Gaeltacht is one such. His error was remedied by a strange figure with a thick moustache and wearing a tweed suit and plus fours, and waving majestically his walking stick like a conductor’s baton. Later he met him again at St Gobnait’s church in Cuil Aodha at Mass conducting the choir in a composition in Irish of his own. It was Seán Ó’Riada who had already begun another musical Irish Renaissance, giving immense gravitas to the native sean nós by scoring it for classical orchestra, its most potent expression being the much-loved Mise Éire. It’s an extraordinarily well-written chapter (Chapter.13, ‘1970 The Killer Chord’, taking us from O’Riada to Horslips) and shows O’Toole at his vernacular and poetic best, taking the ordinary and by alchemical transformation making cultural gold out of it.

One of the recurring themes of this history is the endemic and practised Irish art of ‘knowing but not knowing’, and it is deployed in relation to many issues O’Toole raises. One of the transitions to modernity he tracks is the painful journey from Derry and Bloody Sunday via Widgery and the H-Blocks to the Good Friday Agreement. Again, the writing is powerful, detailed and disturbing. I didn’t need to know as much detail as he shared, but once seen…. His thematic of ‘knowing but not knowing’ also serves to explain many of the scandals and anomalies of modern Ireland — clerical abuse and sexual offences on the part of some clergy; women’s push for access to abortion and contraception; the frauds perpetrated on Irish tax-payers by the rapacious Charlie Haughey, his ‘crimes so flagrant, the official eye must have been strained from constant aversion’. This is often a very funny book, and much of it is dark humour. However, this thematic can be used both playfully and to devastatingly serious effect, as it is for example in his piece, conducted via forensic questioning on the psychopathic murders of both Bridie Gargan, a young nurse, and Donal Dunne, a Co Offaly farmer, which may have been (but was not) unconnected. This case, which connected a double murderer, the attorney general and Haughey, was dubbed by Conor Cruise O’Brien ‘GUBU’, a new acronym for ‘grotesque, unbelievable, bizarre and unprecedented’. For O’Toole, it constituted the noisy proclamation that all was not well in the state of Ireland – so much noise but no signal. It is indeed useful to see the dots lined up (but not definitively joined) by a super-competent journalist in a way that might not have been possible reading the press at the time, and he builds it skillfully over several chapters and time periods. What was at the time a random set of coincidences, ‘an illustration of chaos theory’, in fact, signified chaos itself and byzantine factional mayhem within Fianna Fail. Challenged four times unsuccessfully as the leader, Haughey’s tenure as Taoiseach lasted until 1992, with O’Toole not making much of that other than to imply that his position had been weakened by scandals, the unstemmable flow of emigration, the sexual revolution, and clerical abuse scandals which constituted major challenges to his, by then, outdated version of a Catholic and nationalist Ireland.

When asked for a good general history of Ireland for a first-time visitor recently, and excited by this book, I wondered if I should recommend We Don’t Know Ourselves, but decided against it in case it contaminated her first experience of Ireland – it’s often quite confronting. I also felt she needed something more factual, and simply historical. If she returns intrigued and switched on by her tourist experience, as I expect she will, I will definitely put this book into her hands as I think it’s a remarkable conjunction of clarity, wit and analysis of the inner workings of a culture that is foreign, but also uncannily semi-familiar to me. It eschews the cultural cringe and parochialism, critiques nationalism and the church with passion, and engages in truth-telling (inevitably controversial). In short, I found it very stimulating and informative largely because written from the point of view of an astute, critical and engaged cultural eye who can appreciate both the richness and complexity of his culture and not avert his eyes when it falls short.

Frances Devlin-Glass is a member of the Tinteán editorial collective

Thanks Frances, he is a must-read in the Irish Times or the New Yorker. If he reads any of my stuff, he’ll be after me…..