by Amanda Williams

21/11/2025 Adelaide to Hobart

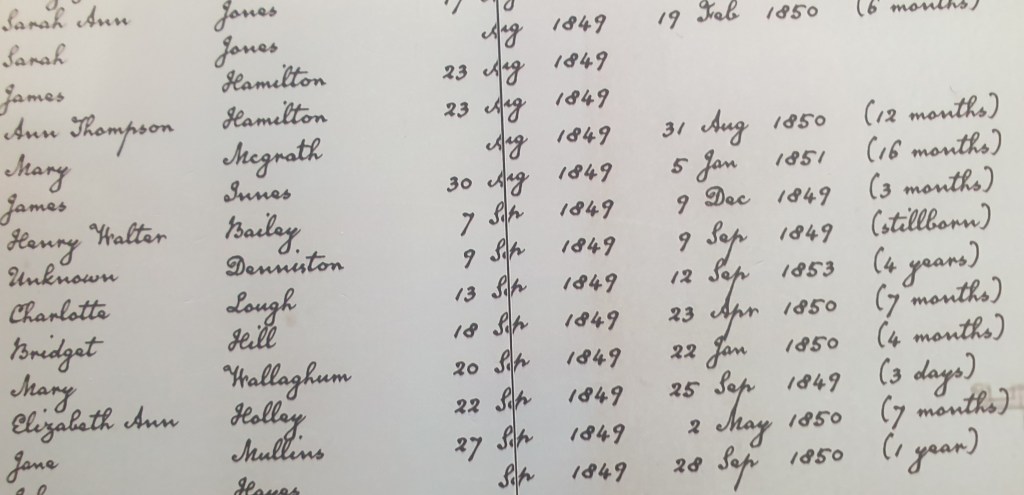

Today I follow in the footsteps of Mary – Mary McGrath, from Waterford, Ireland – my great great great great grandmother, but not as she would have experienced it as she arrived in Hobart Town by ship, as opposed to a featherless bird as I am. Still, this plane is a cargo of passengers of sorts, but none that I know of suffering from dysentery such as Mary and many of her fellow passengers – convicts – on board the Earl Grey, having left Dublin five months earlier in December 1849, and disembarking on a grey May day on the other side of the world in 1850.

I see, just as Mary would have done with her baby in her arms, Mt Wellington hovering in the distance like a benevolent genie behind the busy and bustling township of Hobart. Now, in 2025, it is somewhat hidden behind tall buildings of chrome and glass, but when Mary arrived, the mist and the mud may have reminded her of Waterford, while for me, the pristine docks hide the misery beneath the so-called Apple Isle, Tasmania, Van Diemen’s Land.

22/11/2025

22/11/2025

As I look out of my hotel window into the brick wall of an opposite building anticipating the day to come, my first in Hobart, I wonder what Mary was thinking looking at the brick walls of the Cascades or whether still recovering from the long voyage, and bouts of dysentery, simply being on land was comfort enough for the time being with her baby safe in the nursery with all the other babies, lying head to toe in cramped cribs. Was she missing her husband James and wondering when she would see him again? Her beloved James had been sentenced to transportation for theft, and she stole a cow in the hope of being transported with him. Unknown to Mary, though, James was not to be shipped out from Dublin for another two years. The sadness of her story infuses my morning musings with a familiar melancholy.

Making my way past Parliament House and its grand gardens, Brooke Street and Elizabeth Street Piers, and Constitution Dock, I reach the ‘Footsteps’ Exhibition, a group of three bronze statues commemorating all the women and children who arrived on Hunter Island as it was know then during the time of transportation. I wasn’t prepared for my emotional response. The three statues follow each other in procession, the last with a babe in arms, stepping in unison on their way to the factory, their footsteps covering the plinths etched with the names of the arriving ships. I see the name of Mary’s ship, the Earl Grey, and it all suddenly becomes real, not an abstract piece of history, but a personal realisation when I see that the last statue could have been Mary, baby Mary in her arms. All three, heads bowed, probably out of exhaustion more than shame – out of sadness more than submission – keeping in line, marching forward to the Cascades, Mt Wellington shadowing their movements. I find myself overwhelmed, trying to keep tears at bay, as I exclaim to a fellow tourist and point to the engraved markings ‘my great, great, great great, grandmother was on that ship,’ proud to claim the inheritance.

23/11/2025

The beauty of Hobart Town – the magnificent Derwent, and the mist covered Mt Wellington, pretty weatherboard cottages and the ornate stone buildings – belies the formidable presence of the Cascades Female Factory. Situated five kilometres (three miles in old measurement) from their disembarkation point, for the 236 women and 36 children arriving on the Earl Grey in 1850, the 7,000 or so steps to the factory would seem a final penance or more precisely the beginning of their colonial penal experience. As they walked along the pretty bubbling Hobart Rivulet to the Cascades that in those days ran from its base at Mt Wellington to Hunter Island, they did not know that it would soon become their nemesis as it would often overflow and flood the low-lying factory. This flooding, with its ensuing damp and disease, would cause the deaths of nearly 80 percent of the children in the nursery aged under three.

The Cascades

As I enter one of the two remaining yards of the Cascades factory, now a heritage listed site, I am once again enthralled by the even closer mountain and its steamy shawl of trees and mist looming over the high stone walls that enclose it. Only plates and plaques now mark where women worked, fought, laughed, sang, and cried. I wonder, if like me, they thought, with that mountain so close, so too was freedom: if they could just get over that wall.

The emotive guide told his story well, having his own familial connection to the place, and tears once again flowed, as I found baby Mary’s record of arrival and death: died on 31 August 1850, aged 12 months, having been in Cascades’ nursery for less than three months. I look again at Mary’s convict record in the punishment books and note she was away on assignment in April and May of 1851 and received three days bread and water for being absent without leave, and then a month’s hard labour for absconding again. Then in October of 1851 she was accused of using improper language to her mistress. Was she just so heartbroken and exasperated by her situation with no James to claim her, and now her baby daughter gone? She’d had enough, I imagine. However, the fates were not finished with her yet, and while having on her record the proclamation that she would never live in Hobart Town again as she was that troublesome, she found herself in another factory in Ross, and the beginning of another chapter.

I notice a single red poppy growing out of the barren rocks of the yard and take a photo.

24/11/2025 Ross, 117ks north of Hobart

What I notice first, apart from the oppressive stillness of the women’s factory site at Ross, the second of the convict factories Mary was assigned to, is the sweet Marguerite daisies scattered all over the marked-out bare grass, showing the remnants and sizes of the various sections of the depot. Like the women themselves, the daisies were introduced to the colony. To me, on this windless spring day, they represent the feisty femininity of Mary and her fellow prisoners.

After a short walk, the pretty winding path leads into the little village of Ross: the church steeple rising up and the ornate convict-built bridge a quaint picture that hides its dubious past. I think of the women taking that path too, for some, possibly forced Sunday prayers in the church, being leered at by the male inhabitants, both free and convict, or indeed the women doing the leering, looking for a roving eye to make contact with and to marry as a way out of their nightmare.

Ross to Campell Town 12 ks

Onward to Campbell Town and the convict trail that memorialises in red bricks the men and women who were banished – bani-shed in the Shakespearean pronunciation – the finality of the pronouncement feels as if a commemoration brick seems paltry compared to Mary’s loss and suffering. However, when I find Mary’s brick next to her husband’s, (John Hammerlsey), whom she married in 1853, three years after arriving (her first husband, James, not a viable proposition anymore) the brief descriptions say so much – ‘Mary McGrath, Age 22, Earl Grey 1850 Stole Cow – 7 years – married John Hammersley’ – ‘John Hammersley, Age 19, Surrey 1829 Housebreaking – Life – 13 children’ – John was 18 years older than Mary – she was 25 and he 43 when they married, but she made a life for herself and her family to come. Possibly the loss of two children drove her to make recompense. One of her thirteen children with John Hammersley, Matilda, would become my great, great, great, grandmother.

25/11/2025 Campell Town to George Town

Driving along the beautiful West Tamar Highway heading for Beaconsfield and then over the Batman Bridge and on to George Town, I wasn’t to know the informative and emotional discoveries I was about to uncover, following in the footsteps of Mary and now also Matilda, one of Mary’s daughters who met and married Aaron Jones Jnr. So how did Mary find herself in Launceston and surrounds after Ross? The records show she also spent time at the Brickfields Depot in Launceston and after her marriage to John Hammersley in Carrick (a town south west of Launceston) she and John settled in and around the Pipers River area north east of Launceston where Matilda was born in 1864, and where she no doubt was exposed to the charming, I’m sure, Aaron Jones. Aaron Jones was born in Nile south of Launceston and later lived with his father and brothers in George Town. He and Matilda were married in Holy Trinity church in Beaconsfield, just across the river, in 1883.

25/11/2025 Campell Town to George Town

Loveable Rogues

The Jones family, father and sons, were well known in the area, finding themselves often in court (and subsequently in the newspaper) for many misdemeanours, including helping themselves to others’ wood, both trees and floor boards, letting their horses stray on to others’ land, carting without a license and disturbing the peace. Ultimately three of the brothers, including Aaron, spent a fortnight in the George Town watch house for unlawfully taking washed up cargo from the Astertope shipwreck in June 1883 (he had married Matilda the month before). These brothers, lovable rogues in my imagination, were loved byall related to them, and resented by many who, once again, in my imagination, were jealous of these good-looking opportunists who were trying to make a living in and around the George Town area. So when I arrived at the tiny white pristine watch house, now a museum, its black wrought iron bars, it seemed, werenot only made to keep prisoners in, but also to keep visitors out. I knocked on the locked door to no avail. Checking I had the correct opening hours (I had), I noticed the caveat that followed – ‘subject to volunteer availability.’ Obviously no one was available today.

A Serendipitous Meeting

Crestfallen, but not beaten, I headed north to the Low Head Maritime Museum that held artefacts from the Asterope where at least I thought I could immerse myself in that part of Aaron’s (and by association, Matilda’s) story. Here, to my surprise, was an historian volunteer who apoligised for the watch house being closed. After some initial discussions, she proclaimed her familial connections to these Joneses of the Lower and Upper Marshes and her willingness to share her personal knowledge of these colourful characters. Her passionate encouragement inspired me to write Mary’s story for a wider audience.

From the earlier disappointment, I was ecstatic with the serendipitous nature of our meeting, for had the watch house been open, I may not have visited the maritime museum and would have missed out on the stories of Aaron Jones both junior and senior, and their exploits in and around Mt Buffalo where they lived. After numbers and electronic addresses were exchanged, an impulsive hug (on my part) was completed and more tears (my own) shed on this fact-finding but also inspirational and emotional trip.

As I make my way back down the East Tamar Highway this time to my hotel in Launceston, the lacy mountain tops continue to shape the terrain and direct my eye line moving forever onward in the footsteps of Mary and Matilda.

26/11/2025 Launceston 201ks from Hobart

Mary returns to the picture on my last day in Launceston as I visit the now long-gone inner-city area of Inveresk, now a university and museum precinct, where my great great great great grandmother Mary’s funeral procession left from 12 Dunne Street, on an April day in 1914, aged 84, to her grave at Bangor in the north of Tasmania. Her arrival in Hobart in 1850 in the Australian autumn mirrors her autumnal leaving. She had lived in the northern Tasmanian Bangor region for over 60 years, becoming a remembered colonist and a forgotten daughter of Waterford all those years ago.

Another common theme unites these two poles of home and away, of leaving and arriving. She came from water (Waterford) and left from water: the name ‘Inveresk’ of Scottish origin: ‘inver’, where waters meet and ‘esk’, the North Esk, the South Esk, and the Tamar. Three is always a magic number and the Irish Mary, the Tasmanian Mary and her Adelaide born great, great, great, great granddaughter meet just like the rivers, to mix and mingle, always different, having their own flows to complete, their own journeys to endure, but also connecting through the fluidity of blood and water.

One last stop before heading to the airport and home, the St Andrews Church in Carrick where Mary married John in 1853. A beautiful, imposing white building with a majestic bell tower where all was still, yet ripe with hidden stories that only spaces like these can imbue. An old iron gate opens on to a cemetery of early deaths and infant mortalities, but on a late February day back in 1853, I imagine the trees rustling in a late summer breeze, Mary and John took the long path up to the church doors and crossed a threshold into their new life together, not as convict servants but free man and free woman. The Marguerite daisies strewn about the summer grass, just as they are today, were possibly the only flowers Mary had to mark her nuptials. These Marguerite daisies shadow my trip in the footsteps of Mary ever since noting them back in a Hobart park.

Earlier in the trip while strolling through the delightful village of Richmond and glancing downwards, I saw a tiny wire and wood sculpture on the pavement, an ornament of sorts, of two daisies peeking through an iron fence, obviously dropped by someone, but now mine. Then just now in the churchyard, I stop to pick up a random sprig of white paper daisies, left behind by a grieving or remembering relative. I keep both, entwined together, feeling Mary’s presence just behind my shoulder urging me on, and guiding me to look down, to look back, to continue her story, a trip to Dublin and Waterford already taking shape inmy mind. You never know what you might find about the past and about yourself if you take your time to notice the daisies and to follow the footsteps.

Recently retired from teaching in Adelaide, Amanda Williams holds a PhD in Creative Writing from Flinders University. She is looking forward to spending more time researching her ancestors.