by Emma Ryan

Between 1848 and 1850, thousands of Irish girls sailed to Australia under what became known as the Earl Grey Orphan Scheme. In all, 4,114 teenagers, aged between fourteen and eighteen, were selected from Irish workhouses under this voluntary government-sponsored initiative, conceived, among other things, as relief for Ireland’s overcrowded institutions and as an opportunity for the young women themselves. The scheme’s architects imagined a steady annual migration of 20,000 girls, a plan promoted as mutually beneficial to both Ireland and the colonies. To the Australian authorities, it promised domestic labour and social stability, to the Irish Poor Law Commissioners, relief from overcrowded workhouses. At least that was the theory.

Australia, a British penal colony established on lands long inhabited by Indigenous peoples, had become the destination for transported convicts, followed by a charter group of orphan girls who faced many challenges and prejudices due to their pauper status, lack of education, and often their Irish Catholic ethnicity. Though relatively small in number, these girls left a lasting social and demographic imprint, recognised today almost 180 years after they left Ireland. A recent surge of interest in Irish migration history to Australia has led to the creation of a poignant memorial at Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney, where the names of 420 girls are etched in glass as a mark of their legacy, among them Maria Maher of Portumna.

Origins of the Scheme

The assisted-emigration scheme was proposed by Henry Grey, 3rd Earl Grey, Secretary of State for the Colonies, and administered by the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission. In February 1848, the Commission reported:

‘Having been informed that an eligible class of Irish emigrants may be found among the orphan children now supported at the public expense in Ireland, [we] will be prepared to offer to such of these persons as may, on inquiry, be approved and as may be willing to emigrate, free passages to the above colonies.’

In nineteenth-century usage, the term ‘orphan’ was used not only for children without parents, but also for those who had only one living parent, usually the mother, or who had been deserted. Yet they were treated as if they had lost both. The classification may have helped justify their removal, though many likely had mothers still alive in the workhouse or siblings in neighbouring parishes. It was a bureaucratic rather than a biological definition.

In the late 1840s, inspectors across Ireland reported severe overcrowding, fever, and a growing number of young women ‘fit for service if opportunity offered.’ In 1848, Coleraine Union recorded 218 deserted children on its register; in Mountbellew in 1850, 60 per cent of inmates were children. Poor Law Unions were invited to nominate suitable girls: healthy, moral, and, if possible, literate.

Dympna McLoughlin put it succinctly: the British authorities in Ireland were ‘only too glad to rid themselves, at a cheap rate, of the dependent children and young adults who were otherwise likely to remain a permanent burden on the poor rates.’ The Earl Grey scheme presented a perfect opportunity to rid themselves of this burden. Because of the migration’s long-distance nature, it was almost guaranteed that the girls would not return.

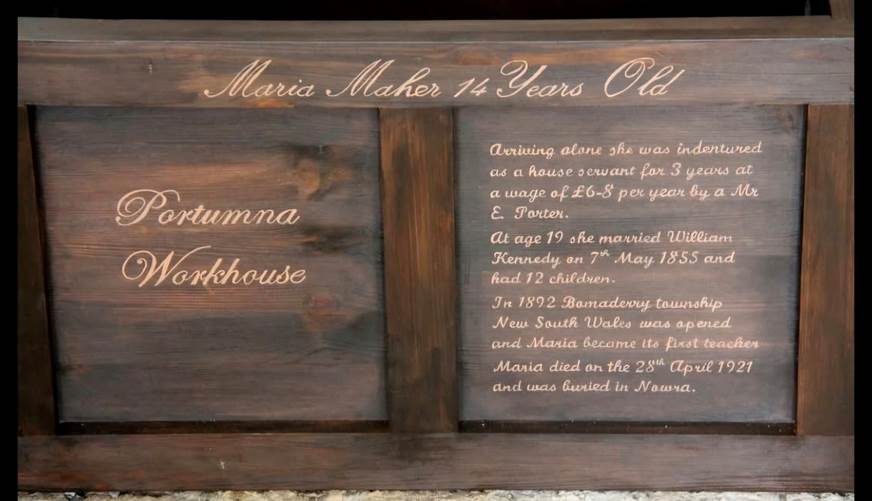

The financial obligation to the Poor Law Guardians in Ireland was minimal: they merely had to pay for transport to the port of embarkation (usually Plymouth, south-west England). Each girl received a small wooden travel box for her few belongings. Today, the Irish Workhouse Centre in Portumna, County Galway, displays two replica boxes made in the Arbour Hill Prison workshops, commemorating the Naughton sisters from Tynagh and Maria Maher of Portumna. Maria left Ireland aged fourteen. According to the Irish Famine Memorial’s orphan database, she left Portumna as a Roman Catholic orphan of James and Margaret Maher (both deceased), sailing on the Thomas Arbuthnot to Sydney in 1850. In Australia, she first worked as a servant and later became a teacher; she married William Kennedy aged nineteen and went on to have twelve children, a single life story that traces the journey from workhouse orphan to colonial matriarch. They carried no money, only a Bible, a change of clothes, and the weight of everything they had lost. Over the course of the scheme, twenty ships carried these girls to Australia. The vessels were operated by the Land Commissioners in London rather than private shipowners, as was typically the case with the ‘coffin ships’ bound for North America. The three-month voyage, though long and arduous, was relatively well organised; the authorities were determined that the girls arrive healthy to fulfil their intended roles. Each ship carried a trustworthy matron who, under the supervision of the ship’s surgeon, oversaw the girls’ welfare throughout. Upon arrival in Sydney, they were lodged in temporary accommodation, a former convict barracks, to recover from the voyage. From there, they were inspected by potential employers and hired out. Settlers, struggling to find dependable domestic servants, eagerly awaited their arrival. Advertisements appeared throughout the colonial press, such as:

The orphans will be landed and lodged in the institution at Hyde Park, where, on some future day, of which due intimation will be given, they may be inspected by such applicants under this notice as have been approved of by the Committee.

The Orphan Immigration Committee strictly barred the girls from employment in inns or ‘houses of public entertainment,’ environments considered improper and potentially compromising to their moral welfare. Instead, they were dispersed across the colonies to private households: Sydney (2,253), Port Phillip (1,255), and Adelaide (606).

This form of assisted emigration proved unexpectedly attractive. There is evidence that some girls even left existing employment to enter the workhouse in hopes of being chosen for emigration. In Mallow, Co. Cork, the Guardians reported that ‘orphan girls in service in the district were leaving their posts and endeavouring to be accepted in the workhouse where they might be chosen for emigration.’ In leaving Ireland, they were also leaving behind the entire structure of deference that had controlled them.

Beyond their labour, these emigrants began contributing to an emerging remittance economy; their small savings linked the two worlds as they sent money home and helped others to follow. For example, in 1856, Ellen Smith, sent to Moreton Bay, deposited £5 with the Immigration Agent (a sum equal to a year’s wages) to aid her family in Ireland. The emotional landscape of the scheme is harder to document than its logistics, yet traces survive; gestures like this reveal enduring bonds to home and an impressive capacity to manage money.

Image: Irish Famine Memorial Trust / Hyde Park Barracks Museum, Sydney. (photo courtesy of Dr Trevor McClaughlin).

Separation and Survival

Given that Ireland’s first workhouses opened only in 1838, and that most came into operation during the Famine years, the girls chosen for emigration in 1848 can be presumed to have spent only a short part of their lives in the workhouse before the crisis of the Famine pushed them through its gates. The description ‘workhouse orphan’ imposed a ready-made narrative of abandonment and lifelong destitution that may not in all cases have been the reality. Many of the girls may have grown up within families and communities before the crisis, not as products of institutional life, but of households suddenly undone by hardship. Most were born before Ireland’s workhouses even existed, and that memory of belonging, however faint, hopefully never left them.

A mother might have watched as her daughter’s name was called, knowing she would never see her again. The emotional toll of this bureaucratic act is almost too great to measure. Few letters, if any, survive, but it is easy to imagine daughters writing from Australia to say they were ‘safe and in service’. Each fragment or echo, we might consider, reveals the deep emotional fabric beneath an apparently administrative scheme.

The girls who had roots within home and community may have drawn from them the strength that later defined their experience abroad. It may explain the steadiness and self-belief many later showed in building their new lives. They carried with them the habits of family life, not the detachment of institutional experience.

Work, Class, and Prejudice

Irish girls were often considered less skilled than their English or Scottish counterparts. They were further marginalised, owing to the Famine’s effects and the poverty they endured; they were described as ‘inferior to English workhouse girls in physical development and personal appearance’. The workhouse children were doubly disadvantaged, having received little or no domestic training.

This lack of preparation did not just make their work harder; it shaped the tensions that unfolded in the households where they were placed. While in their new positions, an interesting dynamic emerged. The arrival of the orphan girls, their very newness, and their place at the lowest tier of colonial society subtly elevated those directly above them. Their presence in colonial households unsettled the delicate emerging class system; by employing servants, often for the first time, their mistresses acquired a sudden self-perception of gentility. In retrospect, this exposes the fragility of class itself, where service and status were performed as much as possessed. In many cases, their mistresses stood only marginally higher on the social scale than their new servants, and without domestic-service experience on either side, conflict was inevitable.

While indentured (contracted) to their employers, these young women had legal recourse to assert their right to fair treatment. Many availed of it, showing an agency far beyond what their vulnerable status might belie. In practice, two overlapping systems operated. The girls could appeal to local magistrates or to the Orphans’ Guardian Board for protection, while employers could prosecute under the Masters and Servants Act to discipline or dismiss them. Some employers, frustrated with what they portrayed as ‘difficult female adolescents’, invoked this Act to bring servants to court for disobedience or insolence.

Such prosecutions carried their own risk. Irish girls were known to defend themselves with fearless candour, ‘in no measured terms,’ as one report observed. The Irish, never exactly known for their inability to express themselves, did so with characteristic pride. Having crossed the world to begin again, they were not prepared to be accused of faults they did not recognise or to endure fresh injustice in silence. The revelations that followed often proved far more embarrassing to their employers than to the accused. In several cases, the balance of power even reversed; although prosecutions were usually initiated by employers, some girls turned the same law to their advantage. In 1851, Mary Connolly successfully prosecuted her mistress for verbal abuse; others, like Sarah Cullins, complained of ‘ill-usage’ at the hands of employers. Beneath these clashes lay a policy failure. The girls may have reasoned, rightly, that if they had received no training to perform the tasks expected of them, they could not be faulted for inexperience; the fault lay with the administration that had sent them.

These young women had asserted their rights and taken a stand against abuse. Far from being submissive victims of circumstance, they helped to end both ethnic and contractual discrimination, standing shoulder to shoulder with other domestic servants of different backgrounds. Perhaps their time spent under the gruelling regime of the workhouse had steeled them in ways unimaginable to a society that sought to take advantage of them.

Sectarian Fears and Public Backlash

Compounding all of this was a ready-made stigma. Former inmates of the Dublin Foundling Hospital had arrived in New South Wales in 1847, and a handful fell into prostitution. Before the first Earl Grey ships even docked, a government doctor asserted that ‘those on the boat were not orphan girls but prostitutes and beggars’, claiming the Emigration Commissioners had been deceived. An inquiry later concluded that ‘great injustice had been done to the colony’. The taint lingered, and the new arrivals bore it.

The utopian ideal of a female migrant of ‘good character’, able-bodied, white, English-speaking, and Protestant, that colonial authorities hoped for was not easily found among the Irish workhouse orphans. Officials feared that Australia was being ‘converted into a province of Rome’. In the assisted-migration streams of the mid-nineteenth century, including Earl Grey’s, Catholics predominated; roughly eighty per cent of assisted migrants were of that faith. Debates in the legislature, Henry Parkes among them, revealed open anxiety about sectarian balance. ‘I for one,’ Parkes declared, ‘am not willing to do anything that will assist in increasing an undue proportion of Roman Catholic power in this country.’

Amid these tensions, and with misjudgements and misdemeanours, real or perceived, accumulating, the assisted-emigration experiment began to falter. By October 1849, employment opportunities had stalled; fifty-seven girls who had arrived six weeks earlier were still without work. The Orphan Emigration Committee responded by lowering its standards, sending girls to employers of a less reputable class than before. Increasingly vulnerable and without protection, they became casualties of a scheme that had lost control.

Opponents seized upon the failures as proof that the experiment had weakened, rather than strengthened, colonial society. In the eyes of the authorities, the orphans had ‘weakened the colonial moral fibre it had sought to strengthen’. Irish girls were viewed suspiciously as a danger to social order, accused of having ‘hoodwinked Irish officials into letting them join the scheme, much to the disgust and delight of the scheme’s opponents in the Australian colonies.’

The Earl Grey scheme was terminated after only two years. The final group of girls left Ireland in April 1850.

Marriage and Legacy

In the colonies themselves, the imbalance between men and women was extreme; in some districts, more than eighty per cent of the population was male. Colonial officials believed the arrival of young European women would ‘civilise’ the frontier through marriage and family, restoring social balance to a society long shaped by convict transportation.

Marriage was advantageous, bestowing a new identity and a measure of stability. Some hid their workhouse origins to escape the prejudice attached to them and to achieve respectability; the fluid class boundaries of a burgeoning colony allowed a social mobility they could never have imagined in Ireland. Once their indenture periods concluded, many followed a pattern of early marriage and numerous children. Raising households of their own, they worked tirelessly to provide for them and to instil discipline and self-reliance. The drive to ensure their children’s survival must have been fierce.

Many married more than once, their first husbands often much older, their unions forged from necessity as much as hope. Through these marriages, they found stability and, in time, belonging, raising families that would become part of Australia’s growing story. Among their descendants are diplomats, surgeons, artists, and teachers, living proof of how far their courage carried them.

These young women were survivors. They arrived without family or friends, lacking any support network, even from each other, once dispersed across the continent. Yet despite the absence of the patriarchal structures of church and kin that had sustained them in Ireland, many flourished, if not immediately, then in the lives of their children and grandchildren. These were girls who became women in Australia: children of famine who came of age in a new world.

Conclusion

The Earl Grey Orphan scheme began as a policy experiment, devised in offices far from the Atlantic wind. It was meant to clear overcrowded workhouses and satisfy colonial demand for servants; what began as social policy became human history. On the decks of those ships, amid fear and seasickness, and perhaps hope, thousands of young women carried a country’s memory across the world.

Whilst they arrived in Australia labelled workhouse orphans, to their descendants they are not remembered as ‘wretched creatures’; regardless of how the historiography might measure their success, they are cherished as matriarchs, and their families are immensely proud and respectful of their memory. They left a legacy in their descendants who helped reshape the continent. The Famine generation was not defined by death alone, but by the strength to begin again. Their story humbles us. It is a testament to endurance, courage, and the quiet heroism innate in the Celtic woman.

The workhouses that dispatched them to the other side of the world have, in most cases, fallen into ruin and silence; others, like Portumna, now serve as places of learning where visitors are asked to remember what was endured within their walls. For much of the time since the Famine, the workhouse was something people did not speak about, a source of trauma, of hurt, and of memories best left alone for those trying simply to move on. It is only in recent generations that we have begun to turn back and face that history, to ask what it meant for the families who passed through those gates. In Australia, names etched in glass shimmer in the light as a living act of remembrance. Our Irish orphan girls are remembered now, with pride and with love, by the families who carry their names and stories across generations as part of the vast Irish heritage that endures in Australia.

Notes / Sources

- Dympna McLoughlin, ‘Emigration from the Workhouses’, in The Irish World Wide, vol. 2: The Irish in the New Communities, ed. Patrick O’Sullivan (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1992), p. 97.

- Irish Poor Law Commissioners’ Reports, 1848–1850.

- Joseph A. Robins, ‘Irish Orphan Emigration to Australia 1848–1850’, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review 57, no. 228 (winter 1968).

- Philip Harling, ‘Assisted Emigration and the Moral Dilemmas of the Mid-Victorian Imperial State’, The Historical Journal 59, no. 4 (2016).

- The Great Irish Famine (Cork University Press, 1996).

- Trevor McClaughlin, Barefoot & Pregnant? Irish Famine Orphans in Australia (Genealogical Society of Victoria, 1991).

- Emma Ryan, ‘They Were Not Wretched Creatures: The Irish Orphan Girls Who Changed Australia’, MA in History of the Family, University of Limerick, 2021.

- Irish Famine Memorial, “Orphan Database,” Irish Famine Memorial website, https://irishfaminememorial.org/orphans/database/.

- Irish Workhouse Centre, ‘Contact’, Irish Workhouse Centre website, https://irishworkhousecentre.ie/contact/.

Special acknowledgement to Dr Trevor McClaughlin, whose pioneering research and publications on the Earl Grey Orphan Girls first illuminated their stories and descendants, and whose work continues to inspire new scholarship and remembrance.

Emma Ryan is an independent writer and social historian from Portumna, Co. Galway. She holds an MA in History of the Family from the University of Limerick.