Dead Man’s Money, written and directed by Paul Kennedy

A film review by Edward Reilly

When Young Henry’s wealthy uncle starts courting ‘The Widow’ Maureen Tweed, he starts to fear that he’ll…

4 Stars

Paul Kennedy does darkling tales quite well. With a one shot thriller, Nightride and episodes from The House of the Dragon to his credit, he has written and directed this very noir take on Shakespeare’s Scottish play. The ensemble is led by Ciarán McMenamin, a writer and noted TV series actor, as Young Henry, and Judith Roddy of Derry Girls plays Pauline, his wife. Pat Shortt, of The Banshees of Inishowen, is stoic Old Henry, while Gerard Jordan as Gerry ‘The Wheels’, and Kathy Kiera Clark, as The Widow Tweed, provide strong support. It’s a shortish film, 82 minutes, and can be taken comfortably in a single sitting.

A hurdy-gurdy is playing a dark drone as the curtain lifts on a black screen. Then there’s a snippet, ‘If were done, when ‘tis done, then ‘twer well, / It were done quickly’, uncurling across the screen like a snake. Ominous signs. Not that far away in kith and kin from Glamis, we are transported to Co. Down. It’s a land of mists and grey fields, lumpy hills and potholed roads. A fiddle scrapes and the title appears, not just Dead Man’s Money, which might have given a hint of another bank heist gone wrong, but also it’s The Ballad of Henry, Henry, And The Widow Tweed.

The first three acts establish the setting, the characters and motivations. If it were not for the grim start, one might think that we’re in for a comedy of bad manners. Young Henry is first seen mucking out after milking his uncle’s house cows, cursing as the old man drives past. ‘Ye sleekit old hoor, ye!’, is about the extent of familial affection witnessed, and the depth of his capabilities as an orator. He’s more of a yapping puppy, uncomprehending of people, ‘Why’, he whines, ‘does everyone in this village have to have a nickname? The Widow Tweed, Jimmy the Poof, Wee Alastair’. Young Henry is not very likeable.

Pauline keeps Kenny’s Bar running. She does all the heavy lifting, whilst he decorates the place, pulls beers after closing time and fearfully guides smokers to the new smokers’ reserve. She is direct, one could say, in her dealings with her husband, and driven to distraction with the possibility of losing the bar, and farm, if Old Henry dies intestate. ‘I want it writ!’, Pauline demands in hard music, while Young Henry equivocates. She is not a woman to get on your left side, and lets her husband know it: ‘You are one stupid, daft, dozy, dip pit, simpleton, hi!’, and we laugh at him for his weakness.

Then, Old Henry, who hasn’t been that well, has enough spark left to be consorting in the Bingo at Magheradooey with the Widow Tweed. Thrice widowed she is. But as Pauline comments, ‘one’s unlucky, two’s careless, but three’s … suspicious.’ This hint of how her mind works, hangs in the air like a dagger. A fox has been let loose in the chicken coop of festering suspicions. Then the mere thought that Maureen Tweed would benefit in some way if, and when, Old Henry were to pass, with all the relatives, and the parish priest, lining up for their share. For his part, Old Henry is quite happy to squire the widow here and there, then he waltzes into the pub, taking off with the current account books to McConkey, the solicitor.

The plot could have gone any of a number of ways. Kennedy‘s script takes us down a boggy path. Some ‘big decisions for the greater good’, as it would seem, are made. But as we know from our reading of politics, history and human nature, nothing good will come of a decision based on personal interest. It creates a vortex in which the innocent, the not so innocent and perpetrators are tested by a ‘vengeful God’ who ‘will not acquit the wicked’. And so, the tragedy is played out to its end, in the gathering darkness. It’s a sad tale, terrible, not for everyone, but would fit into a new version of The Decameron quite easily, with a bitter moral in the tail.

When a movie is advertised as being ‘Irish’, all too often the expectation is of some set of clichés into which The Banshees of Inishowen was apt to fall. The audience expected to have some belly laughs, and got them. Dead Man’s Money is comic in some respects, as the banter and style of expression is earthy, funny sometimes. The characters as real as one would find in the back bar at Port Campbell, of which this film’s setting and characters remind me.

Cinematographer, Conor Rotherham, has complemented Kennedy’s sure direction of action and his impressive skill as a writer of dialogue and plot. Kennedy knows his people, treats them fairly, affectionately, even when having us pass judgement on their very human failings.

Stills courtesy of the Irish Film Festival

Chasing The Light, written and directed by Maurice O’Brien

A film review by Margaret Newman

CHASING THE LIGHT sensitively dissects the spiritual haven’s complicated history, in a meditative and beautiful film.

I’m giving it five plus stars! This timely lode, this documentary …

Not only a must see, this wizardly, exquisitely directed, produced and edited cinematographic meditation on compassion in humankind, is told (and tolled) through the compelling story of the spiritual aspirations of a young binary couple. It touches the tenderest core of a viewer’s ethic, moral code and aesthetic; leaves her activated, thrumming, buzzing and burning on, for days, and days and days …

It is dedicated, in gratitude, to Harriet and Peter Cornish, who in 1973, having seen ‘a little of the world’ and gleaned their own, and that of the many, need for a safe place of holding, peace and healing, sought out and landed on the South West Coast of Ireland. Into the rocky and acute gradients of Beara Peninsula, they construct with no power but from their own bare hands, its horizons its spirit level, the first gateposts, walls and buildings of the Dzogchen Beara.

First their home with their children; in 1992, in a few little decades it was donated, lock stock and barrel, to one of the only two English speaking Lama. He was of the tradition and ancient lineage of Tibetan Buddhism; an Oxford University scholar, Sogyal Rinpoche, founder of the international network of Buddhist centres and groups he named Rigpa (‘awareness of the inner nature of mindfulness’) – for there is to be nil rumbling that somehow this is a swizz. Harriet, had been diagnosed with deadly cancer and succumbed 1991-3. Sogyal Rinpoche achieved global fame and accolade upon having published ‘The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying’ in the US in 1992. Mary McAleese in 2007, then President of Ireland, opens, there, The Spiritual Care Centre for anyone and loved ones, stricken by drastic illness, and turning to Flora Cornish representing family on the podium, claims that ‘your parents have allowed us to see differently.’

The demographic evolves, the centre flourishes, funds are raised to build the first Tibetan Buddhist Temple. It is as ‘a beacon shining there out over the Atlantic’. It is as ‘a wave breaking there’. But ‘ … we are not temple builders, you know.’ Dzogchen Beara. Funds are raised from wealthy benefactors, ‘the hardworking giving all they could’ and the first Tibetan Buddhist Temple in Ireland is built and dedicated there, on the remote Beara Peninsular. An apt translation of Dzogchen is ‘great perfection’.

The continuum of music, minimalist yes, melding Tibetan Buddhist chant, from Michael Fleming, is so intimate it becomes forgotten: where light alone, reflecting and refracting, over boundless depths of Atlantic Ocean seems to expel and expound a very music itself. A lone motorboat chugging relentlessly before its own wake disappears but not from view, to reappear – it is not only time that passes – its trail advanced, a white sailed yacht falters awhile; the lights of two boats at night commune battling, as two stars, parallax, to become one.

Perhaps, let us not allocate ‘hippie dippy’, ‘flaky snowflake’ for they are all unique. They say ‘hermit’. ‘I live alone, I am not seeing anybody.’ ‘What else is there ‘To do’? from Peter. Oh the editing of monologue is piquant. Oh it is reliable. It seeks and finds.

Under the influence of such intrinsic filmic beauty steeped in the transcendental, the verbal mind will wax lyrical … there is K-Theory and Low, myriad homotopologies and homotaxies, bundles and manifold sheaves of oceanscape and landscape. There is skeuomorph. The impact of aerial footage is cataclysmic. Then shoreline is shown as never before at ebb and neap and high tides: one glorious tangential torsion turns sucking, soughing trailing horizontal oceanic waters to elaborated vertical skirting cascades.

It all, all of it, awakens the inner Buddha. I defy anyone not to experience some new insight.

It takes it out of you. There is not simply the little buddha clad in white and green lichen corroded alone by the clime, dreggy and drasty, remote.

Inexperience, not knowing, not having the words in the ‘tricky’ transposing of 2500 years of lineage of practice of devotion to the teacher via, eyes wide open now, a feudal tradition to 21st century vernacular. So, discernment in devotion and obedience is marked up by the 14th Dalai Lama pressing for common decency, and the Buddha dharma, as he hesitates in his flow over ‘a good friend of mine’ and intones: ‘Disgraced!’ The usage is not syntactically sound and we recall the manner of passing on religious secrets via linguistic contortion. That too is intrinsic to Buddhist teaching.

Rank abuse was exposed globally. The Lama resigned into exile, succumbing soon to a cancer. The movie conveys intently, with dignity, the disparate voices, the polarisation of the community, the establishing of zero toleration and of restorative justice. Aged, frail, Peter speaks out his immediate devastation charging that especially those who wrote the letter exposing rank and multifarious abuses 24/7 be held in compassion.

Chasing the light, indeed. Not even a mention of compensation. But Dzogchen Beara is open to anyone.

Stills courtesy of the Irish Film Festival

Margaret Newman is a member of the Joyce community.

Mrs Robinson, directed by Aoife Kelleher

A film review by Sian Cartwright

‘We’re not going to move this agenda with statistics and science. We’re going to move it from the heart.‘ – Mary Robinson.

This inspirational 2024 documentary about Mary Robinson, conducted through interviews, footage and narrative explores her passions for climate justice, human rights and gender equality, all integral to her roles as President of Ireland (1990 – 1997); UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (1997 – 2002) and most recently, as Chair of the Elders, succeeding Nelson Mandela – a group of former world leaders collectively endeavouring to solve global issues.

Filmed attending the 2021 Glasgow UN COP Climate Negotiation Summit, Mary worries about assembled world leaders’ lack of commitment to combat climate change. She imagines the state of the world her newborn grandson will inherit in decades to come and is visibly moved.

As Mary speaks with young women concerned America’s democratic principles will erode under Trump’s second presidency, a framed portrait of Ruth Bader-Ginsburg, lawyer and former Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, hangs prominently on the wall behind her. They have more than having attended Harvard University in common. They both became respected counsel for women’s rights and gender equality reform, using their powerful, ground-breaking positions to advocate for change. Mary notes the divergent paths Ireland and the United States are now taking in their approaches to progressive change.

Raised in County Mayo, looking out from her bedroom window across the River Moy, as a young girl, Mary dreamed about someday making change for the better of society. She loved reading about Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther-King, who challenged injustice. A photo of the U.S. First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, unfurling a copy of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) was inspirational. Mary’s parents encouraged her academic interests, stressing she had the same life opportunities as her four brothers. Her grandfather introduced her to the law to make change; she studied law wanting to make others’ lives fairer, while also becoming aware of her own sense of inferiority.

Mary’s parents’ equal treatment of her and her brothers contrasted with the traditional role of women in Ireland. An Article in the Irish Constitution consigned women to the margins by stating their place was in the home. Mary challenged the restrictions placed on women by the State and Church. While her parents supported her career, they disapproved of her choice of husband – specifically Nick Robinson’s artistic career and Protestant upbringing. Hurt by their objections, Mary married her steadfast suitor, and defiantly, if conventionally, adopted his surname.

As Senator, Mary advocated for legal reforms for family planning and sale of contraceptives to women. Women had tried to overcome the ban by boarding a “Contraceptive Train” to Northern Ireland, purchasing contraceptives there, and on their return, concealing them from the Republic’s border control, thereby risking arrest. Mary put forward legal cases for women’s rights and gender equality while raising a family.

Challenging the criminal sanctions against homosexuality, she took Senator David Norris’s case of intrusion by the Irish State into the private lives of individuals to the European Court of Human Rights. They won the case while the European Court’s Irish judge representative dissented. Ireland was required to change its law. As President of Ireland, Mary ultimately promulgated this. David Norris acknowledged the importance of Mary’s efforts, noting young people are astonished to learn that prior to the 1990s, as a criminal offence, to be gay in Ireland risked life imprisonment. This set the stage for gender equality reform in Ireland, with the 2015 referendum affirming same-sex marriage as a constitutional right.

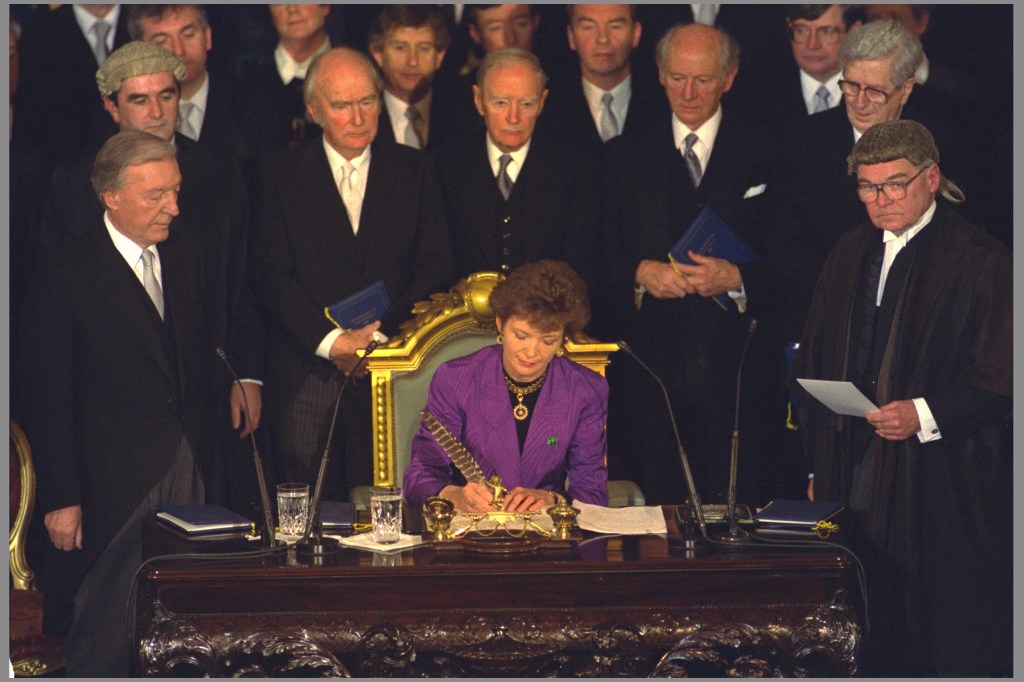

Choosing to run as the first female Labour candidate for the Presidency, Mary challenged the conservative party’s (Fianna Fáil) hold on power which offered 1990s Ireland an expectation of more of the same and a constriction of women’s rights. In a tightly fought campaign, Mary focused on positive change. When a Fianna Fáil MP, Pádraig Flynn, made personal attacks on her, the tide of public sentiment shifted to her advantage. She won the election, becoming Ireland’s first female President.

During her Presidency, Mary kept a light on in an upstairs window at the Áras an Uachtaráin, the official presidential residence in Dublin. This symbolised a welcome return for many in the Irish diaspora who had chosen to leave – the nation had been experiencing high unemployment. In a spirit of reconciliation, she met Irish Republic residents including IRA leader, Gerry Adams, at a local community ceilidh in Northern Ireland, and met the Queen at Buckingham Palace. These events took place with some tension, occurring before the 1998 Good Friday agreement.

Discussing achievements, setbacks and some regrets, as UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, there were frustrations negotiating with competing warlords about relieving famine in Somalia; and trying to negotiate with belligerent Serbian leader, Slobodan Milosevic during the former Yugoslavia conflict. Mary’s friendship with Saudia Arabian Princess Haya Bint Al Hussain is regretted as clouding her better judgment and compromising her integrity. In 2018, the Princess had asked Mary to travel to Dubai for an arranged lunch to help her stepdaughter, Princess Latifa Al Maktoum, who had been trying to escape capture. Mary was misled into believing Latifa was suffering from bipolar disorder, so required the medical attention the royal family could best provide. Instead, after the lunch photographs were published, Mary believed she had naïvely been duped by Princess Haya into siding with the royal family, to the detriment of Latifa’s personal safety and the public questioning of Mary’s actions.

Mrs Robinson is a humane portrait of an inspirational woman whose interests in human rights and climate justice were central to her life trajectory. Mary Robinson imparts a positive legacy as the social justice changemaker she had dreamed of becoming as a child – acting with compassion to improve the lives of future generations, in Ireland and across the world.

Stills courtesy of the Irish Film Festival

Sian Cartwright is Secretary of Bloomsday in Melbourne.