by James Groome

Borrisoleigh to Ballarat and Boorawa

No, it was not the gold discovery that brought me out. In Corrigeen, Barony of Kilmarney, where I lived, seventeen houses were burnt in one day by way of eviction. I at once made up my mind to be under Parker, our landlord, no longer, and I came out here.

These words of Thady Shanahan, a pioneer migrant from Carrigeen in Tipperary to Australia in 1851, gave eyewitness testimony to the evictions that took place on the lands of the Parker brothers the previous July of 1850. They were spoken many years after the fact, in the 1880s, still vivid in the memory of an eighty-six-year-old man.

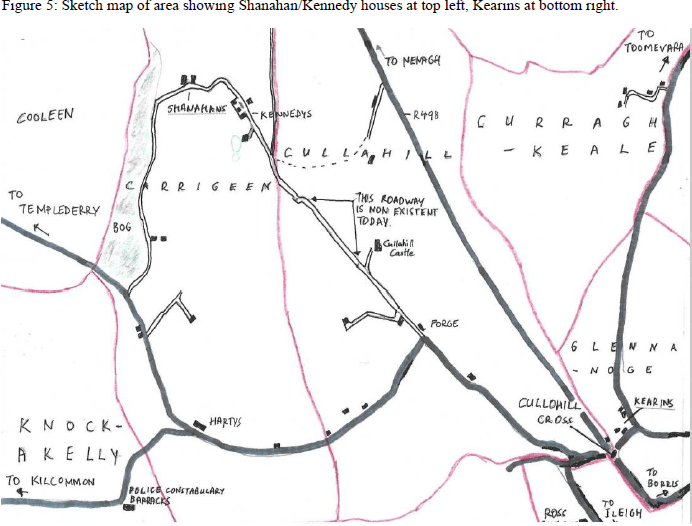

This account looks at the lives of two families and kin groups that lived through the hunger plague of An Ghorta Mór, until the clearances of the land around Cullohill and Kearins Cross on Friday morning 26 July, 1850 when the mass eviction of over 470 people led some to their forced migration to Australia. They had survived the famine, as eyewitnesses to the harrowing events, perhaps just one or two steps above the bottom most suffering stratum, in Oliver MacDonagh’s viewpoint the ‘petit bourgeois of Irish rural society.’ They now faced an intolerable situation: what strategies did they employ to survive, emigrate and thrive?

The Ireland story encompasses the area of seven townlands in the parish of Glenkeen, Tipperary; in Australia, firstly in southwestern New South Wales and then an area northwest of Melbourne in Victoria Australia.

Their story shows that community membership and action in Ireland, on the journey and once landed in Australia was an essential and a vital condition to the family’s continued survival both at home and abroad. The proliferation of the remittance scheme was a tool used by the family groups to expand and continue the migration.

A Founding People

In the context of Irish modern history, the Great Famine of 1845-50 was the greatest of catastrophes whose consequences ‘dealt Ireland a profound physical and psychological shock, which altered the course of the nation’s history’. A quarter of the population vanished, either to the other side of this world or the next. The decades after the famine were the apex point of a mass emigration that has continued ever since and has created a culture of emigration in the Irish psyche.

The works of the eminent historians, Oliver MacDonagh, Malcolm Campbell, David Fitzpatrick and Patrick James O’Farrell’s are comprehensive in the field of Irish Australian studies, and show how the Irish refugee families understood the system, used it to their advantage, and through their knowledge, expertise and hard headedness made sure of the survival, continuation, and proliferation of their family structures and religious belief systems. Their often rural way of life and their distinct ethnic, cultural habits, and customs aided them on their way to becoming, what Oliver MacDonagh has called, a ‘founding people’ of Australia.

Unfortunately, archival sources of these emigrant voices are fragmentary. There are no diaries, no contemporary correspondence of the Shanahan and Kearn* voyages to Australia. However, a close examination of other emigrant’s experience and correspondence, as well as family histories, memories, shipping records, and marine logs have helped to reveal and retell the forgotten stories of the exodus of the evicted families from Borrisoleigh to Australia. The family history documents, made freely available to the author, of the Shanahan, Harty and Kearins* families have greatly assisted in building a picture of post arrival and further family formation and proliferation of kin groups and their successful progression.

The Shanahans and The Kearns

author’s sketch

Borrisoleigh is a small post village in the parish of Glankeen, barony of Upper Kilnamanagh, county of Tipperary… in 1841, it contained 7,481 inhabitants, and the village 1,438 of that number.

On the Friday morning of 26 July, 1850 at Kearns Cross, and closeby at Ross Cottage, home of land agent John Bourke, numerous agents of Government gathered to perform their assigned duty of eviction and clearance of the surrounding townlands on behalf of the recent occupier and landlord John Parker of Ballicotton, Nenagh. Unfortunately this was not an uncommon occurrence in Tipperary of 1850, which had the unwanted distinction of having the highest rate of eviction in the country.

Borrisoleigh is situated where the Kilnamanagh hills meet the alluvial plain of the rivers Clodiagh, and Cromogue. The seven townlands of Cullohill, Cooleen, Carrigeen, Curraghkeale, Glenanoge, Mountkinane, and Glenarisk, are situated at both sides of the road, three on the west side, and four on the eastern with the crossroads of Cullohill at its centre.

These seven townlands, over 1429 acres or 2 ¼ square miles, were completely in the control and ownership of brothers John and James Parker. In the main this was upland, and superfluous to previous plantations, closeby were the extensive Otway and Prittie estates of Lower Ormond, confiscated lands rewarded to Cromwellian soldiers of fortune sequestered in the late seventeenth century from the O’Kennedy and O’Dwyer Gaelic families.

The Catholic parish of Borrisoleigh co-exists with the civil parish of Glankeen. A reported population in 1831 at 6585 rose swiftly to 7481 by 1841, a rise of 13.6% in the decade. Eighty-three percent of families were chiefly employed in agriculture in 1831, and ten years later this figure had dropped to seventy-five percent of families. Sixty-five percent of all families in the parish in 1841 were dependent on their own manual labour as their means.

The tithe applotment books for the seven townlands were assembled in 1832 and show that Cooleen had the most households with thirty-three and Glenanogue the least with five. The seven townlands of eight hundred and four acres had been in the hands of Lord Llandaff of Thomastown Castle in Golden, Co. Tipperary. In 1835 title passed to ‘The Honourable Lady Elisha Mathew only sister and heiress at Law of the Late Right Honourable Francis James Earl of Landaff deceased’. On 29 May 1835, the land was purchased by Anthony Parker Esquire for £9,500. John and James Parker Esqs., Brookfield and Ballyicotton, Kilbarron, Borrisokane, Nenagh, took control sometime after this date. In 1832 there were 110 houses on their property in Borrisoleigh. The land system that was most prevalent in use here was a middleman system with much division and subdivision: the con-acre system was coterminous with potato cultivation and subsistence farming.

Tipperary had already a high level of violence and crime at this time, and the policy of ejectment and consolidation of land was a contributory factor to an increase in agrarian criminality. This already volatile situation was about to be accosted by the single most influential cataclysmic event in modern Irish history- the arrival of the fungus, Phytopthora infestans, which infested and decimated the potato fields of Ireland in that late July of 1845. Death, disease, disorder and departure would soon visit the vicinity of Borrisoleigh.

In April and May 1846 at meetings of the Poor Relief Fund jointly chaired by Church of Ireland Rector Alexander Hoops and Reverend William Morris P.P., a quarter of all inhabitants of the parish were said to be in a ‘state of extreme destitution’ and a subsequent collection was organised with many local landowners subscribing to the fund. The Honorable Mrs Otway Cave subscribed thirty pounds, Nicholas B. Green, Esq., J.P., and William Beamish Esq., with fifteen pounds each, and John and James Parker, Esqrs., Mrs Margaret Cooke and Rev. William Morris, P.P. amongst the ten-pound donations. The Rector Alexander Hoops and both curates Rev. Patrick Morris, brother of William and Rev. James Cormack subscribed to the amount of three pounds each. John Bourke of Ross Cottage subscribed to donate two pounds, as did John Malone, Esq. Sub -Inspector of Police. Thady Shanahan of Carrigeen donated 2s 6d.

Sub Inspector Malone had already been in contact with his superiors in Dublin warning of the impending disaster, on the 15 March he reported

…many people in my district are now opening their pits, the greater part of which are rotten. … I further beg to remark that the labouring class in this town … are in a most destitute state … I fear much that if they don’t get immediate employment, they will take provisions by force.

The situation now facing the population of Cullohill and surrounds was apocalyptic in nature: hunger, disease and displacement, but also threats to security and safety. In May 1847, a correspondent reported in the Freeman’s Journal of Borrisoleigh ‘much alarm prevails among the poor, … should government persist in the monstrous attempt to starve a peacable [sic] suffering people, on their heads will be the destruction of property throughout the country.’

On Sunday 15 August 1847, no longer able to cope with the ‘harrowing scenes of distress among the starving poor’, Rev. Alexander Hoops ‘put an end to his natural life with a pistol by his own hand.’ In September a Borrisoleigh correspondent of the Tipperary Vindicator reported of ‘hundreds of the sick and impotent … all wretched objects of misery … crowd our streets’ seeking relief without any hope of success. In November that year, ‘a poor inoffensive widow named Kerns was barbarously murdered in a field … near Borrisoleigh.’

The situation was increasingly hopeless, as once comfortable families watched their labouring neighbours suffer, starve and separate. The landless labouring poor were the first to starve and suffer as they depended altogether on wages for subsistence. The cold realisation of the impending doom that was facing the population in Borrisoleigh around the next failed potato harvest or non-payment of rent, was all too evident. James Fintan Lalor wrote to the Nation newspaper from Tinnakill, Abbeyleix on 11 January 1847, ‘the smallest landholders of this class were labourers also, … labourers with assurance against positive starvation. Each man had at least a foothold of existence … Their country had hope for them.’ But now this hope was evaporating, and according to Lalor, the policy and purpose of the London parliament was the ‘conversion of the inferior classes of Irish landholders into independent labourers’ and the authority’s belief that ‘the small occupier is a man who ought not to be existing.’ Lalor’s radical ideas of peasant rebellion and proprietorship found much support in the Borrisoleigh area with Father John Kenyon in Templederry and P.B. Ryan, a brewer in Borrisoleigh, ardent supporters. Lalor was arrested in Borrisoleigh on 28 July 1848 the eve of the failed rebellion at Ballingarry Co. Tipperary.

Between 1841 and 1851 the population of Tipperary decreased by twenty-five percent. Instead of an increase in national population to a probable number of 9.02 million, the loss of population between 1841 and 1851 may be computed at 2,466,414 persons. The population removed from us by death and emigration belonged principally to the lower classes- among whom famine and disease, in all such calamitous visitations ever make the greatest ravages.

Locally the population and number of houses in the seven townlands were nearly halved. The population of the seven townlands decreased by 46%.

To be continued

Note on spellings.

Family surnames are variously spelled throughout the records; Shannahan, Shanahan, Kearns,

Kearins, Kerrins, Karrins.

Some townlands are also spelled differently; Cullahill, Cullohill, Glenanoge, Glennanoge,

Glenariesk, Glenarisk, Mountkinane, Moankeenane, Carrigeen, Corrigeen; Barony of

Kilnamanagh, Kilmarney.

James Groome is an independent researcher, historian, Australophile and Tipperary man. He holds a Master of Arts in Family History from the University of Limerick.