Brian Corr: 800 Years of Sadness: … how the Irish overcame despair, disadvantage, helplessness, and sorrow. [Tasmania], 2024.

Kindle Edition: Available on Amazon.com.au

ISBN: 9798334955943

RRP: $9.95

For an Australian with an interest in Irish culture and music and a passing knowledge of Irish history, Irish-born, Tasmanian resident, Brian Corr’s self-published, Ireland: 800 Years of Sadness, is a compelling and punchy read. Corr’s primary topic, summarising Irish heroism and British villainy in Ireland from 1200 AD through to the twentieth century begins with The Great Starvation, or as it is often referred to as The Irish Famine or The Great Hunger of the mid to late 1840s.

The front cover presents an image of an old woman and a harp.

The sad old woman once played the harp beautifully…when the harp was banned and after losing her loved ones through famine, disease and emigration she was overcome with sadness. Centuries later… she began playing the harp again rekindling memories of better times. By reclaiming the harp, she not only honours her past but also inspires, a new generation to remember and celebrate their heritage.

While those with a passing interest in Irish history are most likely acquainted some of the broad facts of the famine, the extent and the details of British brutality and oppression of the Irish during the famine is staggering to read. The denial of food to the Irish, of which there was plenty of during the potato blight, reads as cruel beyond words. Corr labels the actions of the British as genocide and consistent with their strategy of keeping Ireland as a food bowl and a place for absentee landlords to collect their rents from properties won in bloody wars and land clearances. Given the extent of the deaths from starvation, and the bewildering government indifference, the assessment of genocide is hardly misplaced. Corr quotes some of the leading politicians and opinion makers of the day – Lord Palmerston (Prime Minister of the UK 1855-1858, referring to Ireland) ‘…don’t we all agree that the solution to the land problem is get the surplus population off the land?’ The Times (London): ‘We look forward to the day when a Celt will be as rare on the banks of the Shannon as a red man on the banks of the Hudson.’

The main focus and strength of Corr’s book is the work that has gone into listing the heroes and villains, and the extreme eras and acts of British savagery. A secondary intention is to present an alternate history, create new consciousness about what happened, and to correct the histories written by the historians, school masters and politicians. He notes his own and the general ignorance of the Irish population about their history,

In primary school, in Ireland, we passed over ‘The Great Famine, An Gorta Mór’, very quickly, as something embarrassing, something to be ashamed of, to be put aside. Words like genocide, starvation or holocaust were never used in history classes.

The list of events that Corr covers is extensive – the invasions of British monarchs, the Reign of Terror of Oliver Cromwell, the establishment of Protestantism and the subduing of Catholicism, the curtailing and censoring of Irish language, arts and education, the slavery of the Irish in the Americas, the rebellions and uprisings of 1641, 1798, 1803, 1848 and 1867, the resulting Irish emigration, and influential events around the world such as the American and French Revolutions. The clever and devious methods of British rule aside from the executions of rebels and critics that are listed are equally endless – a vast network of spies and informers undermining any Irish acts of independence or economic self-determination, the 1536 Act of Supremacy, King James’ Proclamation of 1625 ordering the transportation of Irish prisoners, The Penal Laws of the 1600s through to the 1800s, the suspension of habeas corpus in the 1790s and at other times, The Sacramental Test – requiring those holding public offices to renounce catholic beliefs, the threat of military force stopping Daniel O’Connell’s Mass Meetings in 1843-45, and the two steps forward one step back progress of the Emancipation Act during the early decades of the nineteenth century, and Gladstone’s Home Rule Bills at the latter end of that century. Other lesser-known events such as the Fenian attacks on Canada, and the escape of Fenians from Western Australia in the 1860s and 70s shed light on the global nature of the endless war that was being waged in Ireland.

Corr’s accounts of those Irish who lead the rebellions and resisted the British in all manner of ways lead to many interesting short biographies – Robert Emmet, Michael Dwyer, Michael Davitt, J.B O’Reilly, John Devoy, and Tom Clarke to mention some. It is mostly a Men Only recounting of the history but there are some interesting cameo portraits of the women as well – Sarah Curran, Maria Fitzherbert, Sister McMullen of the Grey Nuns, Mary Eva Kelly known as ‘Eva of The Nation’, Kitty O’Shea, as well as the callousness of Queen Victoria’s paltry donation of five pounds for famine relief.

Chapters 26-29 headed Easter Rebellion, The Life and Times of Michael Collins and Eamon de Valera, The Assassination of Michael Collins, and de Valera’s Rise To Power, represent the climax of the narrative and bring into view the issues, the events and personalities that lead to 26 counties in Ireland becoming an independent nation and the declaration of an Irish Republic. The tale of the 1916 Easter Rising and the execution of nearly all of its leaders is told in horrifying detail. While the Rising itself was a failure, the events in the following years – the civil war, the arguments over the Irish Free State and compromises with the British, the creation of Ireland’s main political parties Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and Sinn Fein, resulted in independence for Ireland, and the eventual adopting of a constitution in 1937. The most controversial subject dealt with by Corr in these chapters, and of likely most interest to the reader, is the assassination of Michael Collins. Corr states that one of the motivations for writing the book came about from seeing the 1996 Michael Jordan film, Michael Collins. Baldly stated, Corr reaffirms the film’s conclusion that de Valera collaborated in the death of Michael Collins and lured him into a trap. Corr writes, ‘The account… is my best interpretation of how Collins was killed. In the case of Eamon de Valera, the case against him is based on evaluating his actions, not what he or some others said.’

The circumstantial evidence Corr presents against de Valera is reasonably persuasive: Whereas all the leaders of the Easter Rebellion were executed by the British, de Valera avoided their fate, and he and Collins went to West Cork to discuss peace, although after Collins’s assassination, de Valera did not push for peace. He was in a position to convince Collins that he was setting up a major peace conference whilst keeping the anti-Treaty leaders ignorant of his secret invitation to Collins and Collins’s intention to make terms. Corr sees as significant the fact that, although there was a considerable armed escort around Collins, there were no other fatalities or serious injuries on either side. Finally, he argues that there was no official inquest or inquiry into the circumstances of Collins’s death. It’s a great story and has considerable plausibility, but the ultimate assessment is, as Corr himself recognises, is that the hard and primary evidence is not there.

Chapter 29 about de Valera’s rise to power, cements Corr’s opinion that de Valera was a British collaborator and contributed significantly to the continuation of the 800 Years of Sadness. de Valera is painted as the villain:

The dominant religious figure, during de Valera’s time in power… was his close friend, Archbishop McQuaid. With McQuaid’s help, de Valera micro-managed virtually every aspect of Irish life for decades, from religion to education, school to orphanages, resulting in artistic mediocrity, strict censorship, paedophilia, abuse and deaths of children in care.

I feel there is an interesting choice in the writing to be made at this point in the book. Does Corr continue with his racy portraits of heroes and villains or is it time for a deeper analysis? The story of Ireland’s post-independence is perhaps the topic for another book.

A competing or perhaps more subtle analysis is given by Dublin journalist, Fintan O’Toole, in his book We Don’t Know Ourselves. O’Toole tells first-hand his own experiences of the suppression of the Irish spirit by the state and the church from the year of his birth in 1958. He confirms exactly what Corr contends that the partnership of the Fianna Fáil (de Valera’s political party) and the Catholic Church enforced cultural sterility and a continuation of many aspects of the sadness suffered under British rule. O’Toole’s conclusions are quite different, however. He sees it as important that the Irish get over blaming the British and the past for the problems of their contemporary life. He shows how the Irish participated in their own oppression and demonstrates how they began to lift it beginning with the diversification of the Irish economy in the 1960s and the entry into the European Common Market in 1973. The career of Eamon de Valera is oddly reminiscent and parallel to the life of Daniel Mannix, a firebrand Irish bishop, arrived in Australia in 1913 and drifted to the conservative side of politics later in life. No doubt the revelations of Stalin’s atrocities and the torment of the McCarthy Era were as much a part of shaping Irish and catholic consciousness as any villainy in its leaders. It was also a time when the Irish and the Irish diaspora were becoming part of the middle class and were experiencing for the first time a voice in government. In Australia the DLP, a Catholic wing of the Labor movement held the balance of power in parliament, giving the conservative side of politics the ascendancy for 23 years.

Corr’s sub-title for the book, ‘how the Irish overcame despair, disadvantage, helplessness, and sorrow‘, raises some interesting questions. The story of the Irish surviving the domination of the British is an equally incredible story along with the sadness. Time and again the Irish resisted, heroes rose and fell, and the Catholics ignored at great cost to themselves the edicts, the invitations and temptations to become Protestant. Why did the Catholics and the Irish hang on so doggedly to their identity? It must have been worth fighting for and being celebrated when circumstances permitted. Time and time again, the Old English melted into the Irish culture and customs. Was there anything unique about the British domination and cruelty? Colonial powers all around the world showed similar traits. Were the Irish any better when they became masters and landlords in the New World, and was their attitude in general towards Indigenous peoples any different to the British? The case of John Mitchel is illuminating: a man fanatically dedicated to the elimination of British rule and yet an advocate for the continuation of slavery in the USA.

Finally, Corr poses an interesting question in his title to Chapter 24 “Home Rule or Violence?” It’s absorbing to reflect on whether violent or non-violent means of protest were more effective in the establishment of Irish independence. The timing of the famine couldn’t have been worse for O’Connell’s reform through peaceful and parliamentary means, and the call to armed resistance in Thomas Francis Meagher’s ‘Meagher of the Sword’ speech and Smith O’Brien’s conversion to forceful means certainly matched the desperation of the times. Corr describes how effective the boycott became in the debates over land reform, and how the term came into existence. Parnell’s parliamentary manoeuvres also demonstrated the power a minority party can have. Although the brutality of the British forces highlights the British occupation, Corr shows that the main game for the British was economic domination. As Corr notes, Britain wanted Ireland as a food bowl. In the end, it seems, it was the slowly-won economic independence of Ireland from the UK that led to real change for the Republic of Ireland. It seems an irony that today Ireland is flourishing as part of the European Union while the UK is floundering under Brexit.

Overall. Corr’s book is a thought-provoking read. I read it in two days, and would put it in the category of ‘You can’t put it down.’ The book is available on Amazon or direct from the author at www.corr.au

Brian Corr was born in County Kildare and studied computing systems at Trinity College, Dublin. Between 1974 and 2014 he worked in the computer and related industries, during which time he was headhunted to work for an English company in Australia. From 2015 to the present he has hosted Irish radio programs broadcast from Fremantle, Perth and currently a weekly show from Hobart.

Felix Meagher

Felix is a stalwart of the Irish-Australian music scene. Classically trained, he has made a career in traditional Irish music. He was the founder of Lake School, an annual weeklong music workshop for all ages, but especially the young, and he has contributed to the Port Fairy Folk Festival for decades. He is the author and composer of several musical plays, Barry vs Kelly, which tells the story of Ned’s trial, The Man They Call the Banjo (the story of Waltzing Matilda), Adventure before Dementia (a celebration of the life in music of Lou Hesterman) and Runaway Priest (an upbeat musical about clerical abuse and survival).

Ireland 800 Years of Sadness by Brian Corr

‘In all my time immersed in Irish history, the biggest shock was that, first English, then Irish, men, women, and children were shipped across the Atlantic, in chains, and sold as slaves.’

I have to say that ‘shocking’ is an apt description of Brian Corr’s Ireland 800 Years of Sadness. The opposite to what I am used to, and would expect, from a history of Ireland.

Corr’s stance, however, is to counteract most Irish history written ‘from the narrow confines of some academic ‘historians’. His account of 800 Irish years reflects 25 years of research, not only reading Irish history books, but also taking advantages of the ‘much wider knowledge’ available through the Internet. He points out that the study of history at universities is narrow, based mostly on documents ‘professional historians…were allowed to see’, that were ‘written by the “ winners”. Thus, historians “forgot about” Irish slaves until recently.’

‘The Great Starvation’, Michael Collins’s ‘’assassination’’ and de Valera’s legacy of ‘misery and violence’, are other provocative topics. Corr makes his leanings clear. I am not a trained historian, but I am a researcher, and so I read 800 years with my tablet beside me. I have to say that most of my scepticism was allayed as a result of finding back-up information for most of his claims, except for the punishment of finger nail extraction for playing the Irish harp illegally. I wish there had been an index, but I understand the complexity of that. Taking Corr’s approach to history for what it is, I found much that was interesting in his account.

The book has 271 pages encompassing 32 chapters covering 800 years, but there are references as far back as the 9th century. Here Corr finds the oldest reference to an Irish ‘joke’. He provides an origin for the racial terms ‘black’ and ‘white’ and states that Irish ‘slaves’ in the US were deemed to be ‘black’. The Irish patriot John Mitchel once owned a newspaper that supported slavery.

The tone of 800 years is evocative at times of today’s political turmoil: ‘deValera, unable to have the treaty rejected, set about to create havoc.’ There are a few mentions of ‘fake news’. Corr refers to de Valera always as deValera which is unusual and looks odd on the page. I’m not sure if this is a spelling error or something else.

Chapter 32 is a list of recommended reading that points out whether the writer was a professional or non-professional historian. It ends with praise for Wikipedia, ‘a terrific source of information.’

The first three chapters of Ireland 800 Years of Sadness are available free on Kindle and the book is manufactured by Amazon.com.au. You can hear the first seven chapters on Corr’s own podcast at http://www.corr.au/podcasts.html and he can be contacted at this website www.corr.au

Dymphna Lonergan

Book Review by Georgina Fitzpatrick

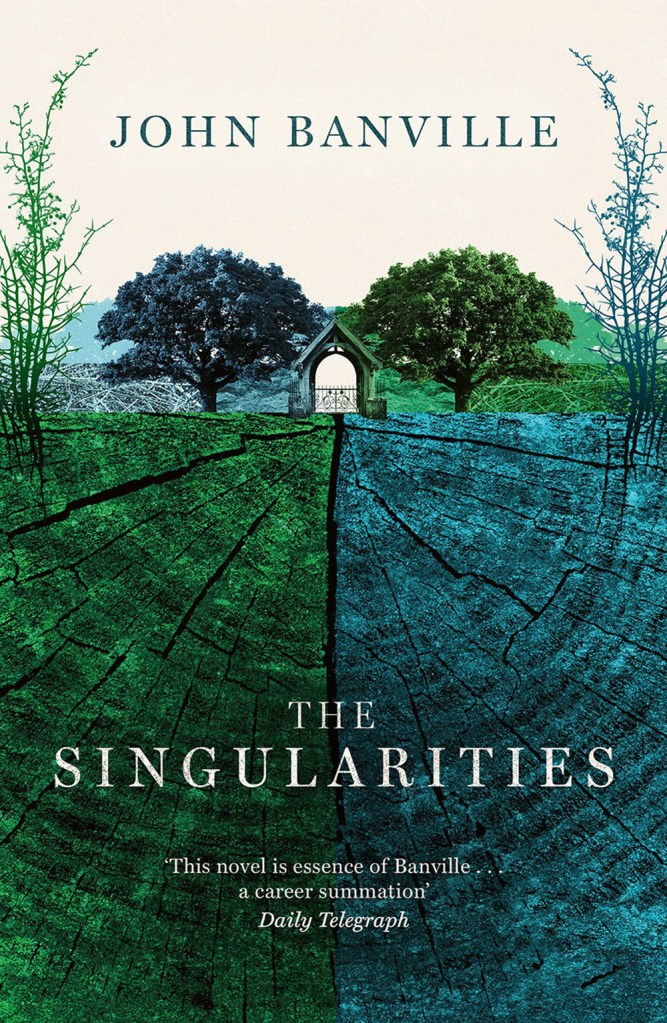

John Banville, The Singularities, Swift Press, Dublin, 2023

RRP: Au $23

ISBN: 9781800753365

This is a very puzzling book. At times, I tried to grasp at wisps and vague tendrils, feeling that a line contained a reference I should recognise but couldn’t quite remember. It would probably help a reader to be more familiar with Banville’s complete works, but I still regard it as a compelling read, even if somewhat challenging.

It begins with the release from prison of Freddie Montgomery, a character from one of Banville’s earlier books, The Book of the Evidence (1989) and based upon Malcolm Macarthur, double murderer, who hid in the Dalkey apartment lent by his friend, the then Attorney General, Patrick Connolly. His discovery after some weeks by the Gardai, theoretically the underlings of Connolly as senior law official of the Republic, played a part in the downfall of Haughey’s government in 1982, an incident which earned the new acronym at the time of GUBU (grotesque, unbelievable, bizarre, unprecedented). Macarthur, released in 2012, has attended book events featuring Banville and engaged with him over his portrayal, an account of which can be found in the most recent book about the murders, Mark O’Connell’s A Thread of Violence (2023).

The fictional Freddie Montgomery decides to change his name to Felix Mordaunt and visit his childhood home, formerly Coolgrange but now called Arden, which becomes the main location of the novel. Despite his air of menace, the current inhabitants – Helen Godley, her husband, Adam, son of the late Adam Godley, famous mathematician, and Ursula, the latter’s widow – allow him to lodge in the cottage of their housekeeper and wander in and out, even though he unnerves them. They are joined at the house by William Jaybey, employed to write a biography of Godley senior. Jaybey (echoing Banville’s own initials) is one of the two narrators; the other being a ‘godlet’ and son of Zeus who is all-seeing into the minds of the characters.

Banville has had fun with this book. For example, there is a chapter explaining Godley’s ‘Brahma theory’ on the existence of infinite universes, a chapter with extensive footnotes and fictitious quotes from invented publications. The theory has, apparently, upended mathematics departments everywhere, New York has been re-occupied by the Dutch and returned to its name, New Amsterdam, or the Grote Apfel, cold fusion has enabled cars to be run on processed sea water, and the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland has been rendered useless and the tunnel flooded.

Many of Banville’s characters from his previous books appear in person or are referred to, including Axel Vander and Cassie Cleave from Shroud ((2002), the Godkins from Birchwood (1973) and Gabriel Swan from Mefisto (1986). Perhaps he is playfully hoping to engage dozens of doctoral students following these trails. He is certainly hinting that this will be his last book in his final sentence:

…the steel tip advances along the line, with a tiny secret sound all of its own, scratch scratch, scratch scratch, and at the last makes a last stab, to mark a full, an infinitely full, stop.

Readers may prefer the crime books he writes as Benjamin Black, set in 1950s Dublin, particularly enjoyable for a holiday read, but Banville has enticed me into his universe again. I now want to re-read some of those earlier books on my shelves.

Georgina Fitzpatrick lived in Dublin for 20 years and followed the Macarthur case at the time.

Note: Our late lamented editor, Frank O’Shea, reviewed Harry McGee‘s true crime account, The Murderer and the Taoiseach, of this set of events in the December 2023 issue of Tinteán.