Extended Review by Jules McCue

To mark St. Brigid’s Day, 1 February

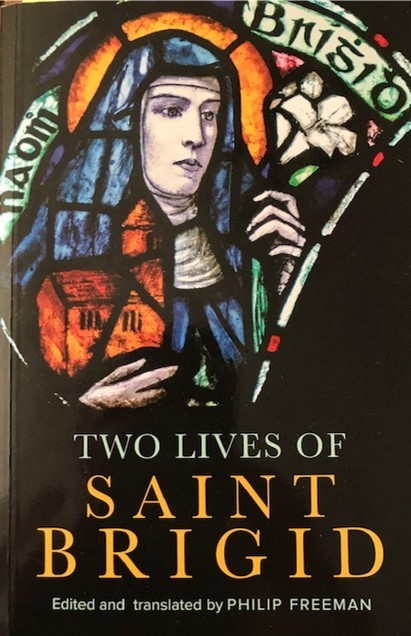

Saint Brigid – Between Two Worlds and from Place to Place: some thoughts after reading The Two Lives of Saint Brigid, edited and translated by Philip Freeman, Four Courts Press Dublin, 2024.

We are fortunate to have ancient sources that attempt to tell the story of Saint Brigid’s life. She has always been highly venerated and recorded as having played a significant role in the spiritual and cultural life of Early Christian Ireland, as well as being adulated in Scotland and other parts of the European continent; the Hebrides are named in devotion to her. Her fame and glory are celebrated today, perhaps in a different way from the early Christian adoration. Nevertheless, her popularity is gaining strength, with the day of her death once celebrated as a feast day and now, as a public holiday in her home country, at the beginning of the Imbolc season on February 1.

In 2024, Philip Freeman, a Latin and Early Medieval scholar, who holds the Fletcher Jones Chair at Pepperdine University, published his translation of two of the hagiographic stories of Brigid’s life. There are a variety of spellings for her name: Brigid, Brigit, Bridget and several diminutives or sobriquets: Brida, Bree, Bridie, Bride, and the translations into Nordic such as Brigetta (or Brigitta) and Brigida. Philip Freeman has used Brigid in his 2024 translations: Two Lives of Saint Brigid, so this article will proceed with this spelling.

The first of Freeman’s translations is the mid-seventh century Life of St Brigid by Cogitosus, whose Latin, Freeman says, is quite polished. The second version of the saint’s life is the Vita Prima whose author is anonymous, the Latin quite good but not as refined as the former. Freeman says he tries to adhere to the content and the style as much as possible. There is a third version of her life written in Old Irish and a fourth written in Latin, Bethu Brigte which is preserved in only one Medieval manuscript. Due to Brigid’s popularity since her own time, there were many of the former two versions in circulation. For the purposes of his translations, Freeman has selected those he thinks are the closest to her time and are the most reflective of the original texts. We know that scribes and early Christian scholars inevitably contaminated their translations or copies with their individual language interpretations or their personal or religious perspectives.

Cogitosus’ version is less than half the length of the Vita Prima. The latter contains most of the miracles and events of the former, but there are many more such items, miracles being the narrative structure of the two Lives. It is interesting to read both presentations, considering they would have used similar sources, these being the oral stories passed from one generation to another prior to the introduction of reading and writing in Early Medieval Ireland.

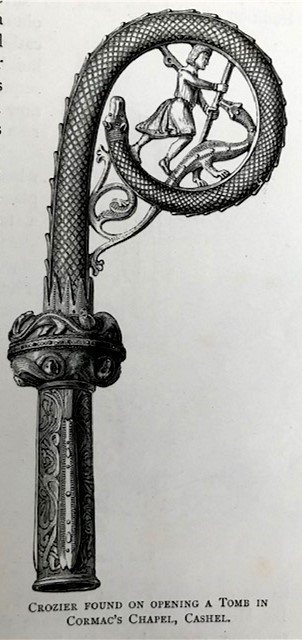

Whilst St Patrick [d.493], whom St. Brigid [c. 450 – 525] supposedly met and worked with, could read and write, though he says himself that his Latin is poor, we assume that she had neither skill, hailing from an island country that was not educated in the arts of textual literature. Patrick arrived in Ireland with a few clerical companions, bishops and priests from Gaul [France] armed with the tools of conversion such as literacy in Latin, perhaps Greek, copies of the scriptures, catechisms, and missals to enact the sacraments. Some carried croziers, a symbolic long-stemmed hook that emulated the shepherd’s crook. Naturally, having lived amongst the Irish as a youth after being kidnapped into a form of slavery, Patrick spoke Irish but his companions spoke other Celtic languages. These were the weapons the clerics took into the battle of transitioning the Irish people from Paganism to Christianity. To do so as swiftly as possible, Patrick’s mission was to train more of what were mostly Irish men initially, generally from the noble ranks, he needed to teach them Latin, just as it was essential for clerics from the continent to learn Irish, to spread the word of God in the vernacular language. In the words of E.A. D’Alton [Vol.1], within a century after Patrick had begun his mission in Ireland, ‘there were no less than three hundred and fifty Irish lives whose names were enrolled among the saints’, men and women. He tells us that Patrick was a powerful, diligent, and determined man. After reading the Lives of Brigid, you could endow this forceful but patient woman with the same attributes and above all piety and humility.

Before delving into the Lives of Brigid, it is necessary to place her in the context of the fifth century AD. We know that Patrick and his followers had been working assiduously to convert the Irish from what was a life of trembling fear and dread of constant war, human sacrifice, a ritual offering to appease the angry gods, slavery, and for women much more. That does not mean to say that life in pagan Ireland didn’t have some redeeming aspects. The law was very entrenched in everyday life and much of the law was based on secular life guarded and administered by the Brehon law-makers. There are various sources preserving these early law tracts which have been studied and interpreted thoroughly by many scholars over the years. There were laws protecting women and children, but as paganism has been whimsically revisited over the past two centuries, with a degree of wishful thinking, the role and conditions of women have been romanticised through a belief that women were better off before Christianity, and that it was a matriarchal society. On the other hand, there is the camp that believes there could be no doubt that women’s lives were ameliorated by Christianity. Neither side of the discourse is completely true. Christianity brought with it a cult of admiration for virginity and celibacy, though pre-Chrisitan Irish parents were not agreeable to this new cultural phenomenon.

Pre-Christian and early Christian Ireland were intellectually and imaginatively alive with the spirit of creative freedom and vivid minds, inspired by a constant flow of fresh ideas and information from other countries. Before the age of writing, the Irish were forced to commit all to the mind. In fact, druidical ways often preferred that content was not written down, preserving secrecy and mystery. The socio-cultural collective knew the stories of the old sagas, the structure of the spiritual otherworld, the almanacs of the seasons and the genealogical history of theirs and the noble families. When writing and reading were introduced through formal institutions, the Irish were directed to Latin, the language of the Romanesque empire of the Cross, the conduit through which a rapid conversion would be manifested and spread centrifugally throughout the known world of Europe, the middle east and north Africa. They also diligently studied the bible and Greek and Latin literature; their knowledge of which was later able to be reproduced throughout Irish and European monasteries so that ‘western civilization might be saved’ after the desecration and looting by various northern hordes during Europe’s Dark Ages. Kathleen Hughes (The Church in Irish Society, 400-800, pp. 301-329, A New History of Ireland, Vol 1) tells us that early Christianity in Ireland was part of the orthodox European Church but was somewhat unconventional, similar in flavour to Egyptian practices. She says that the imaginative detail found in Irish secular literature also appears in some of the religious literature. These characteristics emulating the fantasy of the sagas and the magical miracles Christ performed in the New Testament, pervade the mythical aspects in the Lives of Brigid and those of many Irish saints.

Some historians and commentators have a romanticised version of this spiritual invasion, saying it occurred almost bloodlessly. A.E. D’Alton begs to differ and tells of the war on the plain of Tara where Patrick and his followers slew many of the forces of the Irish King Laoghaire who refused to change his ways. History and events during our lifetime tell us that people don’t change their whole belief system overnight. What we perceive by specifically studying the lives of the saints is that the spirit of pre-Christian Ireland never completely left the Irish mind. The Lives of St Brigid are excellent examples of the syncretism of thinking and perception that persisted in the culture of Ireland from paganism to Christianity. A very poetic example of this continuum is manifested in the story told in the two Lives of the time Brigid was soaking wet from a heavy downpour; when she walked inside the house and was asked to remove her wet cloak a sunbeam shone through the wall and she casually hung her cloak on it without any magic spells or fuss, rather it was natural and mystical to her, as she was intoxicated by God. Such was how her piety and close connection to God were conveyed in these narratives. In the second version of Lives she is referred to as ‘holy Brigid’ and the author always starts a story with such phrases as “A certain bishop” or “A certain king” or “A certain church,” etc. If one is interested in the real topographical and historical context of her life, this uncertainty is extremely frustrating. Surely, the original author/s knew from the oral history they received and the times and dates though bumpily passed down, who that king, or bishop was or which monastery, clan, or church she visited. In one of her travels, she goes to Munster with her companion Bishop Erc, a convert who was also a judge it seems, and nearby is a Mount Ere, of which designation is found no trace or similarity. Fortunately, the authors do give some explicit details of places and related kinship groups, many are easily recognizable, several are allusive.

Variations of her birth, parents, and early life

We know definitively that Brigid is famous for her foremost establishing of a monastery to house monks and nuns and a splendid church on the “Curragh” of Kildare, a large flat limestone based, fertile and grassy plain. She built her settlement near a river and notably an Oaktree, hence the name kil [church] and dare- daire or [oak tree], a specimen having much significance throughout many stories across Ireland. Much of the information and anecdotal text about Brigid’s life and work, available through other sources, is not documented in the Lives translated by Philip Freeman. There are so many snippets under a plethora of subjects on the internet, as well as bits and pieces found in history and other books. One such, is that the king of Leinster at the time had an embarrassing physical feature, being born with ears like a donkey. He asked her to ameliorate his situation. When he inquired as to what favour he should give in return, she said she wished for some land. When he asked how much land, she spread her cloak on the ground. Perhaps another example of her humility, one of her main virtues. When she performed the miracle favourably, he gave her the whole of the Curragh.

There is another version, as is often the case, that tells that a prominent man mocked Brigid who needed land, saying that he would give her as much land ‘as her cloak would encompass.’ When Brigid placed her cloak on the ground it continued to grow and spread across the plain, enabling her establishment to cater for a sizeable community (Frank Delany, The Celts, p. 178).Though her timber church described in Cogitosus’ Life of Brigid as having beautiful wooden-carved elements, paintings, and linen wall hangings, has long gone, replaced by a Norman style stone cathedral, the ruins of which remain today and the remnants of her smoke house wherein a perpetual flame had been lit from her time till the time of the Tudor destruction of the Irish religious establishments in the 15th century. It is prudent to take all anecdotes and information, including the Lives translated by Freeman, with a grain of salt, a mineral highly sought after in these stories having significant symbolic power.

There is much conjecture about whether she was originally from Kildare or as most often thought, from the Louth region. Her father was a Leinster chieftain, Dubhthach (there are several mentioned in connection with Christian assemblies and prominent roles). The chieftain was married but he preferred Broicsech a slave he had purchased. The site ‘Catholic Medals’ explains that she was Portuguese or from the then western Iberian Peninsula. These Irish of the north and east coast made frequent raids on Britain and parts of the continent as well as frequent raiding at home due to internecine fighting.

Eventually, Brigid was brought back to her father, as she wasn’t part of the transaction, only her mother. It is said Brigid was born neither inside or outside the house as at the time of birth, her mother had one leg inside and the other out. Is this a symbol of Brigid’s status in the continuum as the triple goddess in the pagan otherworld and the holy virgin in the Christian world? Some sources say that Brigid was born into paganism and she was either converted by successful persuasion as a young girl or that she sought out this divine God and as is the saying, was filled with the Holy Spirit. No matter who were her parents, where she was born or when she converted, Brigid must have been extremely charismatic in some way, for her ability to draw powerful kings, bishops, their unending material and spiritual support and most especially, the texts tell us that she spent considerable time with the eminent St Patrick before he died.

Her nun-hood, her skills, her ambitions

In the Lives we are told that when Brigid did meet up with Patrick in the north, he insisted that she must always travel with a priest from that time. She seems to make many journeys included in the Vita Prima of Saint Brigid, though much fewer in Cogitosus’ version. She obeyed the patriarch and took protection but was it a way to control her, as she was adored by so many and had much autonomy in her life: she had power. Perhaps he was concerned for her safety. In the accounts presented in these Lives we can perceive that control over women in a new sense is evident. Even Brigid applies some curious miracles, ‘. . . holy Brigid blessed a woman fallen after a vow of integrity and who had a pregnant and swollen womb . . . Brigid restored her to ‘wholeness and repentance’ interestingly, ‘. . . by the conception shrinking without birth and without pain.’ Like many of her miracles Brigid herein is described as having ‘healed’ the woman and ‘gave thanks to God’ as she and the receivers of God’s divine power always do in these far-fetched incidences.

On another occasion Brigid throws a lump of silver into a river to teach a lesson to a stubborn nun and the story unfolds in the usual pattern closely following the narrative of Christ’s miracles. As Brigid is a cultural continuum in the Irish psyche drawn out from the earlier pagan Triple Brigid, who was a metal worker [smith craft], healer and goddess of poetry, is this lump of silver therefore an indication of what crafting she and her nuns might carry out as part of their world of production, as many miraculous incidences in the Lives describe the baking, the provision of abundance from scarcity, turning water into wine and beer, carpentry and even road building. Somehow eventually, her name becomes synonymous with fire, the hearth, and the inner world of the home.

In these accounts of her life, several are presented about her relationship to animals, mostly wild and usually threatening. A wild boar appears and with her blessing becomes tame and protective amongst her swine, similarly wolves guard her flocks and there are episodes of communication with ducks, horses, etc. The film Babe comes to mind and many others, as we would wish to communicate with our animal friends.

Her journeys and companions – the roads the saints

Road building in early medieval Ireland, as mentioned before, was an integral part of life, for the tribal members were expected to build and upkeep local sections. One miracle in the Lives describes in detail the building of a significant road, perhaps part of the road once near or on the long ridge of the Esker Riada, named the Slí Mhór, parts of which are still used today travelling between Dublin and Galway. In order to make her kinfolk’s labour easier, she moved the river and as was stated, the old river bed was still evident at the time the Lives were written. Most fascinating are the details of her journeys throughout Ireland, the names of her travelling companions, the names of the territories, rivers, and the places visited, many of which must have been accessed along the ancient roads.

Much history can be gleaned from these two of Saint Brigid’s Lives and it is better to have them than not. One cannot help but wish that every king, chieftain, guest house, river, mountain, church, and monastery had been given a name. Philip Freeman’s fine translation of the Two Lives is a much-appreciated and entertaining edition.

Sources Consulted

Two Lives of Saint Brigid, edited and translated by Philip Freeman, Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2024

History of Ireland: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day, The Reverend E.A. D’Alton, Half Volume 1 to the year 1210, The Gresham Publishing Company Ltd, London.

A New History of Ireland, Volume 1, Prehistoric and Early Ireland, ed., Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005

Katherine Simms, Gaelic Ulster in the Middle Ages: History, Culture and Society, Trinity Medieval Ireland Series 4, Four Courts Press, Chicago, 2020

Origins and Revivals: Proceedings of The First Australian Conference of Celtic Studies, edited by Geraint Evans, Bernard Martin and Jonathan M. Wooding, Centre for Celtic Studies University of Sydney, 2000

Frank Delany, The Celts, Grafton Books, London, 1989.

Jules McCue is a Wollongong based artist, musician, writer, teacher, and independent researcher. She has written many essays about artists and their work, for example: Extraordinary Exhibition: Holy Threads: Savanhdary Vongpoothorn, [1998]; Black Man in a Whiteman’s World: Indigenous Art in NSW Jails [1998] ; Allan Mansell: The Creation of Visual Stories from an Original Tasmanian [2012]. Her Masters Dissertation: Wildflowers and White Porcelain and Circles and Seeds: a study of the History of Women Artists through Still Life Painting [1994], University of Wollongong. Conference Papers include Not Surrealism, Magical Realism [1995], Katheen and Kitty: Two Women; a painter and a composer/pianist, both of Irish heritage [2019], and Historical Ireland: control and cadastrophe through stories of circumjacent mythology, weird and wonderful, ambiguous shapings of the

vigorous mind [2021]. Email: julesmacarts@gmail.com Website: julesmccue.com

There is another great Ms ‘Early Christian Ireland by M.T. Charles-Edwards. From a review “This is the first fully-documented history of Ireland and the Irish between the fourth and ninth centuries AD, from Saint Patrick to the Vikings – the earliest period for which historical records are available. It opens with the Irish raids and settlements in Britain, and the conversion of Ireland to Christianity. It ends as Viking attacks on Ireland accelerated in the second quarter of the ninth century. The book takes account of the Irish both at home and abroad, including the Irish in northern Britain, in England, and on the continent. Two principal thematic strands are the connection between the early Irish church and its neighbours, and the rise of Ui Neill and the kingship of Tara. The author, Thomas Charles-Edwards, is Professor of Celtic in the University of Oxford“