Land ownership in Ireland, Part 2. by Tomás Ó Dúbhda

The Land League

There had been occasional resistance, to some of the worst landlord atrocities both before and after the Great Hunger/Famine. The groups responsible for this resistance were usually known as Ribbonmen or White Boys and used tactics such as anonymous letters of intimidation, driving away landlords’ cattle etc. In spite of those involved, or alleged to have been, often being condemned to transportation to Australia, or sometimes death, some were driven to such desperate measures rather than face eviction and starvation. A new, non-violent and infinitely more effective means of resistance began to emerge in the 1870s, a peaceful form of intimidation that had never been witnessed in these parts before and which would quickly spread far and wide. This new departure brought immediate, short-term benefits in some cases but, for various reasons, the fight to achieve any tenant rights at all, would continue into the 20th century, in some other cases.

(Connaught Telegraph)

A number of Tenants Defence Associations and similar groups had been set up in response to Gladstone’s Land Act of 1870 which aimed to provide some rights for tenants, similar to those enjoyed by tenants in Ulster. Essentially these were the three Fs; fair rent, fixity of tenure and free sale, which had been sought by the tenantry. Although Gladstone’s intentions had been noble, the act largely failed to achieve what it set out to do but another precedent had, at least, been set. James Daly, joint owner of the Mayo newspaper the Connaught Telegraph, who had been calling for land reform, called for a similar association to be set up in Mayo. The Mayo Tenants Defence Association, later the Land League, became a nationwide movement which ultimately saw the demise of landlordism, to be replaced by a system of owner occupiers, or tenant proprietors.

Whereas almost all of those evicted during the Great hunger had been overwhelmed by the weight of numbers against them, now the Land League organised mass meetings of thousands to protest against proposed evictions. They got hundreds to attend at the houses where evictions were to take place and they also provided legal advice and other support to those under threat. In addition, the widespread use of photography helped to boost support for the cause of the campaign not just locally but at an international level, politically. Although Michael Davitt is widely credited, or Charles Stewart Parnell, with the establishment of the Land League, and the mass meetings which were so integral to its success, the man who was responsible for setting it up was James Daly. In January 1879, tenants of Canon Bourke’s Irishtown estate near Claremorris, Co. Mayo, who were threatened with eviction, asked Daly to publicise their grievances in the Connaught Telegraph. He arranged a mass meeting which was attended by an estimated 10,000 people and forced Canon Bourke to rescind threatened evictions and reduce rents by 25 per cent.

Some may be surprised to discover that a Catholic priest was a landlord; this is not quite so unexpected. A relatively small number of Catholics managed to hold on to some of the wealth accumulated in earlier times and it was customary for such families to have at least one son become a priest. Canon Bourke had inherited the estate on the death of his brother, who apparently had been understanding of his tenants’ difficulties in the previous few years and had allowed arrears to build up. Apparently, the Canon showed no such understanding and moved to immediately evict all those in arrears. The type of solidarity shown by those who attended the rally in support of the tenants would be part of the plan, along with a no rents payment scheme and ostracisation of land grabbers and recalcitrant landlords which was adopted in the forthcoming campaign.

The successful Irishtown meeting provided a template for the Mayo Tenants Defence Association, established in August ’79, later the Land League of Mayo, before finally becoming the National Land League. Daly was elected Vice-President and the support of Davitt and Parnell gave further impetus, although Parnell’s own political ambitions were less than helpful later on. So began the campaign that resulted in the beginning of the end not just of the landed aristocracy but, some would argue, the end of British rule in Ireland. Under pressure of the ‘land war,’ the government in 1880 established a commission under Lord Bessborough to examine land law in Ireland. Daly’s evidence to the commission was impressive, it strongly influenced Bessborough to recommend radical, or what Westminster considered radical, land reform in Ireland.

Gladstone, the Prime Minister, responded in 1881 with the Land Act by granting tenants the ‘three Fs’ which they had sought; fair rent, fixity of tenure and free sale. It also established the Land Commission which had the power to buy estates that were in financial distress and to re-distribute these lands. Tribunals were established to fix rents judicially for a term of fifteen years. The mere fact of these rights being established in legislation did not mean landlords quietly acceded to tenants demands that they be implemented on the ground. Some fought these measures tooth and nail by every means available to them. The courts system had been, and continued to be, weighted very much in their favour but they were more than capable of resorting to intimidation and other foul tactics when they felt these were warranted. Although the granting of the three F’s was a major departure, and some rent reductions were achieved, in reality, this Act was mostly ineffective.

Far from suddenly disappearing, landlordism lingered into the 20th century but, although the amount of land which changed hands in the immediate aftermath of this legislation was relatively small, due to inadequate funding, the power of the landlord class would never be the same again. It should be noted that the British government did not willingly make any of these concessions out of the goodness of their hearts. As had been the case many times before, the initial British reaction had been to use the stick first, only resorting to the carrot afterwards. The Land Commission was established under the Land Act 1881, and was empowered to buy these estates and offer the tenants the opportunity to buy the land. This, however, was not the end of the land struggle in Ireland. Many of the landlord class were not in financial difficulty and therefore not prepared to sell their estates.

To be clear, when we talk of landowners, we do not refer to the small or medium farmers who rented from the landlords and we certainly do not include the cottier class, or the farm labourers, who usually had no more than a quarter acre on which to grow potatoes to feed themselves. Land ownership refers to those who had legal title to large swathes of property which they rented in various sized parcels to their tenants. Many of these, known as absentee landlords, did not live on their estates but employed managers and agents to administer the estates on their behalf. It was these agents who earned the worst reputations of all, one of whom was the infamous Captain Boycott of the Lord Erne estate, near Ballinrobe, Co. Mayo.

He is quoted as believing in the divine right of masters over the servant class and is said to have imposed ever tighter controls and restrictions on the tenants until they finally revolted when he threatened evictions. In August 1880 they withdrew all labour and the Land League called on local shops and businesses to refuse their services to Boycott and his people. Although Orangemen from Cavan and Monaghan arrived to reap the harvest, it is said to have cost the British government and others roughly £10,000 to save a harvest worth about £500. The value of the propaganda victory for the Land League is impossible to estimate, and the English language had got a new word at the end of this particular campaign.

The tactic of boycotting quickly spread throughout Ireland as the campaign continued for rent reductions. In 1879 the West of Ireland experienced catastrophic weather conditions in the Atlantic coastal counties, temperatures had been lower, overall rainfall and the number of rainy days were all roughly 20% higher than the averages in the previous decade. Oats and hay harvests fell in some areas by 14% and 10% but potato yields fell by a massive 56% and the number of sheep and pigs fell by 15% and 27%. The potato was a large component of the animals’ diet, which greatly contributed to the fall in their numbers. The loss of sheep and pigs was severely felt as their sale would normally pay the rent. The cumulative effect of such losses was that most tenants simply did not have the money to pay the still high rents.

The lower than usual turf harvest meant many were going to have a greatly reduced source of fuel for heat and cooking. It is no exaggeration to say that the spectre of famine loomed very large and many were at their wits end. The need for some relief measures was glaringly obvious. The Local Government Board/LGB reported to the government that ‘much suffering and sickness was anticipated.’ They concluded, however, ‘that the Poor Law Unions would be equal to the demands.’ The Catholic bishops took a different view, stating that ‘the existing Poor Law is insufficient to cope with the coming crisis and that it is the urgent duty of the government to take effectual measures to save the people from a calamity.’ Colonel Deane of the LGB, having met some gentlemen farmers at a market in Loughrea in Feb ’81, reported to Dublin Castle that ‘although there was considerable want, the distress was much exaggerated. With this attitude, we see a repeat of the almost casual indifference witnessed during the Great Hunger.

Politicisation of the campaign.

By this stage, the land question had become inextricably linked with the broader nationalist question. Whereas the three F’s had been all that the tenants had sought back in the 1850s, their patience had been exhausted and things had changed by now. As previously uncontested parliamentary seats had been won from the landlords by those of a more nationalistic outlook, we saw many of the MPs lend their support to the Tenant Defence Associations and the Land League. Whereas some Catholic bishops clearly opposed the resistance of the tenants’ groups, others lent their full support. Rather than the tenant being cut off from any support, as in earlier times, their concerns were now uppermost on the agenda of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) in Westminster. As the Gaelic Athletic Association/GAA, the Celtic Literary Revival and the Gaelic League/Conradh na Gaeilge developed and grew from the 1880s onwards, many of the same players took leading roles in each organisation. There was now a coherent desire to be free of the old imperial restraints and to cast off those shackles in their entirety and many of those campaigning for change, such as Douglas Hyde, Countess Markievicz, Lady Gregory etc., were of the old Establishment but openly called for a new approach, some eventually being involved in the 1916 Rising.

The Plan of Campaign

Although the 1881 Act had led to rent reductions of roughly 25%, it became clear by 1885-86 that even the reduced rent would be too much for many tenants after two years of bad harvests, which were not foreseen when the new rents had been agreed. Although some landlords agreed to a compromise, many did not and so the Land League organised a No Rents Campaign. In October’85, Davitt, in an address to a demonstration in Kilkee, Co. Clare said ‘If the landlords band themselves together to resist a just demand for a just reduction, the people must combine in order, by every justifiable means in the constitution, to resist the inhumane right of eviction for non-payment of such rents.’ Referring to evictions, he went on ‘Wherever a holding is thus made vacant, we must see that it remains so and we must see the evil that is the land-grabber shall not thwart the popular movement…We will be perfectly justified in following the example of landlords who boycott Nationalists in trade and business, it cannot be wrong on our part to boycott the land-grabbers and landlords. Kilkee was home to the Vandeleurs, a landlord family notorious for their absolute refusal to contemplate negotiations about rent reductions.

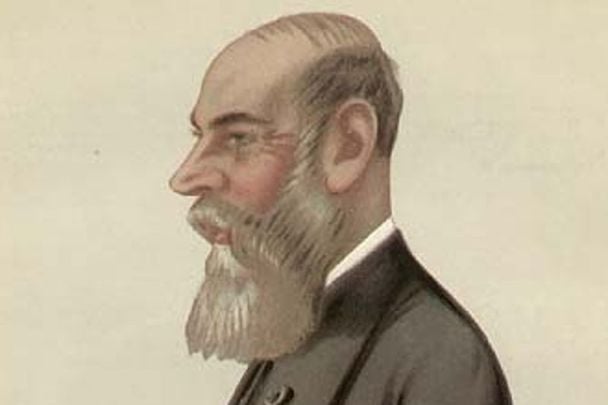

In 1886 the scheme known as the Plan of Campaign was launched. Where a landlord refused to lower rents voluntarily to an acceptable level, the tenants were to combine to offer him reduced rents. If he refused to accept these, they were to pay him no rent at all but instead contribute to an “estate fund” the money they would have paid him. This fund was to be used to protect and maintain the tenants who might be evicted. Land-grabbers, as before, were to be boycotted. Among those who refused point blank to negotiate was the Earl of Clanricarde, the English born heir to the vast Burke family estate. This old Norman family had seen their 13th Century swathe of large parts of East Galway enhanced further under the 1652 Act of Settlement. The earl, who also had a substantial estate in Kent, and was related by marriage to the former Prime Minister George Canning, had a reputation in London of being a reclusive oddball. Whether it was his oddness, stubbornness or sheer greed that drove him we cannot say but he absolutely refused to negotiate and used every means at his considerable disposal to break the campaign of his tenants.

Although large numbers of police and soldiers were sent to the Woodford area of Clanricarde’s estate, resistance was fierce. Roads were dug up and people barricaded themselves in houses when evictions were expected. Not only did the local clergy and the Bishop of Clonfert lend their full support but the international press coverage generated political support far and wide. The name ‘Saunders Fort’, where the attempted eviction of the Saunders family took days to complete, showed the gross injustice of the full weight of the government being lent to a very wealthy Englishman who had rejected the offer by his tenants to purchase their farms in accordance with the 1881 Land Act. There were also protracted disputes on the Vandeleur Estate in Kilrush, and the O Callaghan Estate in Bodyke, both in Co. Clare. The O Callaghan case is interesting as this was an Irish Catholic family that had been transplanted from the more fertile land of Co. Cork under the 1652 Act of Settlement. Colonel (retired) O Callaghan was not at all amenable to the idea of a rent review, in spite of the greatly reduced market prices available to his tenants, due in part to agricultural imports from USA and Australia.

The demand for reduced rents continued and the government, almost incredibly, introduced yet another Coercion Act in 1887, the Protection of Persons and Property Act. Among its powers was one to arrest without trial anyone “reasonably suspected” of crime and conspiracy. It was the case, however, that the only crime of those arrested may have been to support the aims of the Land League but, in the eyes of the authorities, this amounted to conspiracy. Hundreds were imprisoned at any one time, including Davitt, MPs like Parnell and John Dillon, an MP of the normally more conservative Irish Parliamentary Party which was more concerned with parliamentary autonomy rather than land rights. Some may find it noteworthy that ninety years later the British government was still pursuing a similar policy against a section of the population in Northern Ireland.

Wyndham Land Act 1903

The Land Purchase Act, introduced by Chief Secretary George Wyndham, was the first piece of land legislation to include a provision for compulsory purchase. By now, the number of landlords who wished to sell their land had dried up but demand from tenants for a comprehensive settlement of the issue of ownership continued. The successor to the Land League, the United Irish League (UIL) had campaigned for the break-up of large grazing farms and their compulsory purchase. As these were let on an eleven-month basis, and deemed un-tenanted because they were let for less than a year, they had not been subject to previous schemes, which focussed on tenant purchase only. A conference of landlord and tenant representatives took place in December 1902; the agreement they reached formed the basis of the Wyndham Act the following year. Although this was amended by a 1909 Act to include compulsory purchase of tenanted land because some landlords still refused to sell voluntarily, this act is seen as the one which signalled the (British) governments acceptance of the end of the landlord system.

The following report from the Western People, a local newspaper, gives us a flavour of the optimism which the new land system generated. ‘Our Claremorris reporter informs us that the Abargnall farm, convenient to Milltown, consisting of over 200 statute acres recently purchased by the Congested Districts Board (CDB), is being striped for sub-division among the tenants and that building operations will shortly commence. Already there are over thirty men employed daily in striping the land. When the lands are duly striped and all operations are completed, it will undoubtedly help to make for the prosperity of Milltown’. The term ‘striping’ is a description of the layout of the farm land allocated by the CDB/Land Commission. As land often tended to be more fertile closer to the road, and often of poorer quality further away from the road, a general rule of thumb was followed for allocation. This involved fencing/striping into long narrow fields running back from the roadside house. Thus the area used for potatoes and other tillage was usually close to the house, beyond this would be the better pasture and then the poorest land. This was sufficient for summer grazing during which time the better grazing land would be ungrazed for the growing of hay for winter feed.

‘Well, you may call it voluntary, we forced it out of him.’

The financial implications of the changed conditions can best be seen in the following case. At an August 1907 Royal Commission on Congestion, Tom Connell, Bekan, Claremorris, Co. Mayo, an area quite close to the first mass meeting at Irishtown in 1879, testified that he took over a property of 35 statute acres on the Dillon estate in 1865 at age 20. He rented from a middleman, or agent, Frank O Grady, whom he described as ‘a man who had said once that a high rent was the best manure that was ever put on land, a tyrant and a very bad agent.’ That the reduction of rents was the principal focus of the Land League in the area was indicated in Tom Connell’s explanation of how his own rent fell from £24 per annum to £15 in 1879. When asked if it was a voluntary reduction, he replied, ‘Well, you may call it voluntary, we forced it out of him.’ The Land Court subsequently reduced it to £12! In 1898, Tom Connell and his neighbours purchased their land holdings under the Ashbourne Act, through the Congested Districts Board, which also carried out drainage works in the area. The initial annuity, the price of purchasing the land from the government, was £7, later reduced to £6 under the 1903 Wyndham Act, exactly quarter of the 1865 rental. Before the Land League, Connell said, ‘the produce of the holding nearly all went to the landlord. The people are living better now than they were then, and they are better clothed.’

(The Life of William O’Brien, the Irish Nationalist, by Michael MacDonagh, 1928 Ernst Benn London)

Tom Connell spoke before the commission as a respected community leader. It was said within his family that he had been involved in the failed Fenian Rising of 1867 and was elected to the Claremorris Rural District Council in 1904 representing the United Irish League. The UIL was an organisation founded in Westport in 1898 and which spread nationally afterwards. Their primary aims were to provide poor relief to relieve distress, to deal with migration from the countryside, to redistribute the estates to prevent further famines, to end the cruel evictions and to ostracise so-called land grabbers. Members approached local landowners to persuade them to sell their estates to the CDB, rather than to land grabbers, to enable the tenant farmer to bring up his family in decency and comfort. It is interesting to note that Tom’s son, T J Connell, trained as a primary teacher and served as a Labour TD/MP for Galway in the first Dáil/Parliament of the newly independent Irish Free State from 1922 and, later, for Mayo. It is extremely unlikely he could have availed of that level of education had the old land ownership system remained in place. My thanks to Dr. John Cunningham and Niamh Puirséal of National University, Galway for the information on Tom Connell.

Although this is just one example for which we have accurate records in the public domain, it is considered to be fairly representative of the changes that took place in the twenty plus years following the 1881 Act, when the unfettered profits of the landlord class were no longer deemed absolute. As stated above, the 1903 Wndham Act was the single most effective piece of legislation enacted by the British Parliament in facilitating these changes. When rural Ireland no longer had to support the lavish lifestyle of the parasitic gentry and the small farmers began to enjoy a somewhat comfortable way of life, it gave the lie to all the earlier propaganda of the indolent, lazy Irish being the cause of their own misery and starvation. When one remembers there had been 175 Committees and Commissions of Enquiry over a short period prior to the Great Hunger, one has to speculate how many of the three million who died or fled the country might have survived, or not had to flee, had any British Government of the period actually had the moral courage to make even a start on some of the changes so strongly recommended by the committees/commissions they themselves had appointed.

In Part 3 we will look at what happened after Ireland finally won her independence with the birth of Saorstát Éireann/The Irish Free State.

Tomás Ó Dúbhda grew up on the Mayo/Galway border in the 1960s. He studied Archaeology, History and Irish at the University of Galway and has maintained an active interest in each of these areas throughout his life, including the derivation of placenames, the Great Famine period, and the Land Ownership question. He has been involved with a number of heritage and historical groups, attending seminars and field trips in counties Clare, Galway, Longford, Mayo, Offaly, Roscommon, Sligo and Westmeath.