by Tomás Ó Dúbhda

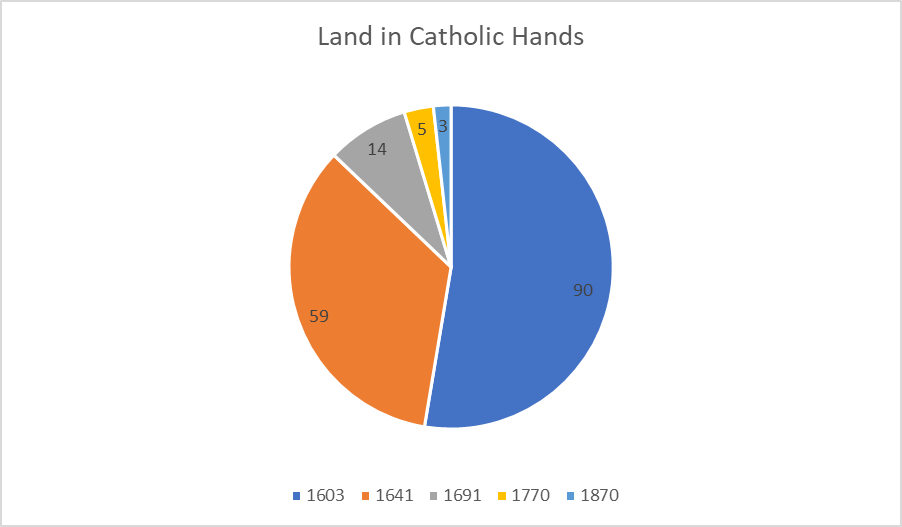

After the defeat of the Irish, led by the Ulster Chieftains O Neill and O Donnell, at the Battle of Kinsale in 1602, there followed a series of confiscations, plantations, most notably in Ulster, and the implementation of the Penal Laws, with the result that the amount of land in Catholic ownership declined sharply in a series of stages. In 1603 90% of land was still in Catholic hands; by 1641, after two series of plantations, this had fallen to 59%; by 1685 to 22%, in 1691 at the end of the Williamite War, to 14%, by the 1770s to 5% and by 1870 to as little as 3%.

Cromwell in Ireland

In 1641, after decades of dispossession/plantation and systemic religious discrimination, the Native Irish in Ulster rebelled. The rising quickly spread nationwide and thousands of Protestant settlers were killed, along with thousands of Native Irish also killed in retaliation. With the end of the Civil War in England in 1649, Cromwell lead an army of 12,000 troops to crush the rebellion in Ireland and to avenge those Protestants massacred earlier. Where Irish resistance was fiercest, he used ‘slash and burn’ tactics, leaving the Irish without food or shelter. This led to deliberate famine and associated disease, with a population loss of roughly 25%.

With war drawing to a close in 1652, Parliament passed the Act of Settlement which specified who would forfeit land in Ireland. As well as those known to have participated in the initial massacres and those who fought in the war, the act also targeted prominent Catholic and Royalist leaders and Catholic clergy alleged, though not proven, to have incited the rebels. The Down Survey 1656-58 was the first land survey on a national scale in Britain or Ireland for about 600 years. It sought to measure, survey and map the land to be forfeited by the Catholic Irish to facilitate its transfer to Adventurers and English soldiers.

The Adventurers were those English people who had financed the re-conquest of Ireland. In effect, this was meant to leave all the land, except for most of Connacht, including Co. Clare, in the hands of English, and some Scots Protestants. Even in parts of Connacht, in the area around Galway City and especially in Connemara, we see members of the ‘Tribes of Galway’, wealthy merchants descended from the Normans, and Old Norman nobility like the Earl of Clanricarde, displacing the old Gaelic lords like the O’ Flahertys and others. One of the O Flahertys, Rory, or Roger as the English called him, was granted a little over 400 acres of very poor land in exchange for the thousands of acres of better land he had formerly owned. That he retained any property at all was down to his being considered a ‘gentleman’, having been reared by an English landed family. This practice of “fosterage” had been common among the Irish lordships for hundreds of years and, occasionally, as in this case, included fosterage in England.

Go West

All the other Gaelic landowners now found themselves reduced to the role of tenants, liable to eviction at the whim of the new landlords. We also find evidence of family names formerly associated almost exclusively with one area starting to appear in another area. For example, among the East Galway surnames that are widely found in West Galway/Connemara after this period are: Shaughnessy, Hynes, Kelly, Madden, Mannion, Egan, Murphy, Donoghue, Feeney, Geary, Molloy and some others that occur less often. These were forced migrations as the lands they formerly owned were assigned to other Catholics who had in turn been ousted from their lands in other counties to make way for the Adventurers and soldiers. In 1704 we see a measure, as part of the Penal Laws, ‘to prevent the growth of popery’, which restricts landowning rights for Catholics. Under this law land must be sub-divided among all sons/heirs, unless the eldest son converts to Protestantism, in which case he inherits the lot.

Griffith Valuation

Quite how small the majority of land holdings had become, and how poor the housing, mainly as a result of the 1704 Act, is evident after the completion of what is known as Griffith’s Valuation in the 1830s. This survey was to update the earlier data to establish who the owners and occupiers were with a view to raising more taxes for the Treasury in London. From this survey we see the first six inch maps of Ireland which, along with the above data gives a definitive account of who lived in each of the townlands and villages at this time. In the process of doing so, the names of all the townlands, parishes etc. were to be given an Anglicised form to facilitate British record keeping. For taxation purposes houses were divided into four classes, with the first class, those of the big farmer and professionals valued at £20 and the poorest, the mud/turf cabins of the cottier and labourer class at 5 shillings, a valuation one eightieth of the homes of the highest class.

The Great Famine/Hunger 1845-52

The result of decades of land sub-division, as a result of the Act of 1704, and a rapidly increasing population, along with the suppression of the woollen and linen cottage industries which had once flourished, had resulted in the great majority of tenants, especially along the West coast, being left with tiny subsistence landholdings. That they survived at all was due to the potato crop which could sustain a large number of people on a small area of land. When the new form of the potato blight struck in late 1845, it led to years of the most awful catastrophe. Blight had occurred from time to time previously but never for a second successive year, much less eight. Given the total lack of government response initially, and the absolute inadequacy and premature ending, of the subsequent responses, the outcome was inevitable. The subsequent population decline has been estimated at about three million, roughly “one million dead and two million fled”, as was said afterwards.

Most, though by no means all, of this population loss occurred along the West coast, from Cork to Donegal, where most of these small holdings existed. To fully appreciate the extent of the devastation, whether caused by death or emigration as a result of the hunger, disease and eviction, one needs to compare the Griffith maps with those from the 1880s. Most of the house clusters, or clachans, that we see on maps from the 1830s have disappeared, along with the large numbers of small fields where there often are no houses left. We see fields that are many times larger, reflecting the replacement of small sections of tillage with large-scale grazing. Today, a hundred and fifty years or more after the clearances, we can still see sections of the new, higher walls that were built to keep the livestock from wandering.

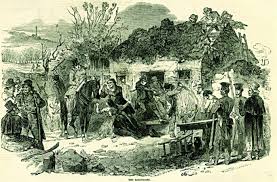

Evictions and Emigration

As tenants were unable to pay their rent, evictions became quite common. There had been some clearances on a limited scale in the preceding years. These clearances occurred where landlords decided it would be more profitable, and less troublesome, to rent large tracts of land, in lots stretching to hundreds of acres, maybe thousands, to one grazier rather than hundreds of lettings to tenants in much smaller holdings. The reduction in the amount of land devoted to labour-intensive tillage farming led to less work for labourers, leading to a big increase in emigration. As most of these had only the ground on which their houses stood, and relied mostly on a potato wage, they faced the workhouse or destitution if they stayed put. Even in 1852, at the end of the Great Hunger, but with the Encumbered Estates Court (see below) fully effective, it was estimated by the authorities that 369,000 emigrated. When Britain had been at war with Napoleon up to 1815, there was more demand for agricultural produce and the Irish accounted for up to 40% of the greatly expanded British army; neither of these employment safety valves was available on anything like the same scale at this time of greatest need.

The level of evictions increased substantially after Black ’47 when substantial arrears began to accumulate; with virtually no rent being paid, many landlords decided the time was right to evict. The clustered houses referred to above indicate a group leasing of land under the Rundale System. Whereas nationally about 8% of land was held under this system, in parts of the West it was 40%, or higher. These were group leases which provided some little protection to individuals and, as poorer and poorer land was cultivated, it led to a high degree of co-operative effort, as it was more difficult to create drills for potato planting on the higher, rougher ground.

Ironically, these very labour intensive drill systems were derogatively referred to as ‘lazy beds’ afterwards. Whereas landlords saw the group arrangement as a benefit traditionally, these larger areas now became attractive to clear in one go. What had been a quite limited amount of ‘clearances’ prior to the Famine, increased subsequently both by established, often absentee, landlords and the newer, speculator class of landlord who started to appear after the Famine.

As the sitting tenants had no lease, they were there at the whim of the landlord and could be evicted without notice. In some cases, such as the notorious 1846 mass eviction in Ballinlass, Mountbellew, Co. Galway, entire villages/clachans could be wiped out at a stroke. The population of the village at the 1841 census was 353, in 1846 it’s believed it had risen to 447, by 1853 it was 4 with just one house remaining where once there were sixty six and this was the house of a herd, not a tenant farmer. This happened at a time when the demand for land, and rents payable, had never been higher as a result of huge population growth over the preceding forty to fifty years. The really shocking thing about Ballinlass is that there were no arrears of rent due and the tenants were willing to pay the rent but it had been refused when offered.

When the Belfast Newsletter sent a Col. McGregor to investigate, he found that ‘the story was perfectly correct, and the numbers dispossessed by no means exaggerated’. It was alleged at the time that the tenants had allowed some additional people to take over some very poor, boggy land without paying extra rent to the landlord, Mr. Gerrard. Apparently it was argued that, if this were true, it was not a matter for the tenants to be concerned with, as it was not part of ‘their’ land but rather that the landlord should have dealt with the matter himself. It was even suggested that Gerard was happy to have these other people there simply to use this as an excuse for eviction, having conducted clearances previously on another area of his estate and, indeed, did so again in the following years. The term Gerrardism became synonymous with mass eviction clearances throughout the Western region in the following years.

The Encumbered Estates Court 1849

Although, as we will see, this court did nothing to advance the cause of tenants, it was a hugely significant step for the British Parliament to take. By intervening in order to facilitate the financial sector’s interests, no argument could be sustained in future when intervention to safeguard the interest of tenants was called for. It was established to facilitate the sale of estates whose owners were unable to meet their financial commitments to lenders. The sole purpose of the Act was to empower banks and others with a claim against the estate so they could expedite the sale. There was no clause to protect the interests of tenants, in fact many purchasers who undertook, prior to purchase, not to evict tenants but to provide long leases, did indeed pursue a policy of eviction afterwards. We see a marked increase in clearances to make way for a greatly increased incidence of pastoral farming. With the introduction of the Act in 1849, there were even more clearances before the sale, to make the estates more attractive to prospective purchasers. As the lenders only concern was to see the mortgage cleared, some of these estates were offered for sale at considerably less than their market value, thus attracting a new speculator class of landlord.

The number of tenancies would have fallen as a result of the Great Hunger; that they fell substantially afterwards is confirmed by some unlikely sources. Sir Thomas Larcom, the chief executive of the British administration in Ireland was moved to note the sharp reduction in the number of land leases in the 1850s and ‘60s. In 1851 alone in the nine months from April – December 4,793 people were evicted in Co. Galway and 5,696 in Co. Mayo, two of the worst affected counties.

Rev. Denham Smith, a Protestant clergyman, commented on the ‘depopulation of Connemara’ and the Galway Vindicator condemned the Law Life Society of London/LLS for the ‘extermination’ of Connemara. To make estates more attractive to prospective buyers, the LLS, and other financiers, pursued a relentless policy of eviction.

One of the new speculator class of landlord now emerging was John George Adair, who already had substantial estates in Tipperary, Laois and Offaly. He evicted 47 families comprising 244 people in Derryveagh, Co. Donegal in 1861, having purchased the land from the Encumbered Estates Court. This was an area where the land could best be described as marginal but, when cleared of all tenants, was an attractive proposition for low-maintenance sheep farming. It could be let in large holdings to a grazier who might employ a herd, or two, with no concern about crop failure and consequent rent arrears. He later acquired the neighbouring Glenveagh and Garton estates, giving him a total of about 28,000 acres.

Although the days of the Great Hunger had passed, tenants still had no reason to feel at ease about their future livelihood and wellbeing, by now the pattern of fleeing the land in search of a better life elsewhere was firmly established.

Tomás Ó Dúbhda grew up on the Mayo/Galway border in the 1960s. He studied Archaeology, History and Irish at the University of Galway and has maintained an active interest in each of these areas throughout his life, including the derivation of placenames, the Great Famine period, and the Land Ownership question. He has been involved with a number of heritage and historical groups, attending seminars and field trips in counties Clare, Galway, Longford, Mayo, Offaly, Roscommon, Sligo and Westmeath.

Tomás Ó Dúbhda grew up on the Mayo/Galway border in the 1960s. He studied Archaeology, History and Irish at the University of Galway and has maintained an active interest in each of these areas throughout his life, including the derivation of placenames, the Great Famine period, and the Land Ownership question. He has been involved with a number of heritage and historical groups, attending seminars and field trips in counties Clare, Galway, Longford, Mayo, Offaly, Roscommon, Sligo and Westmeath.