by Tomás Ó Dúbhda

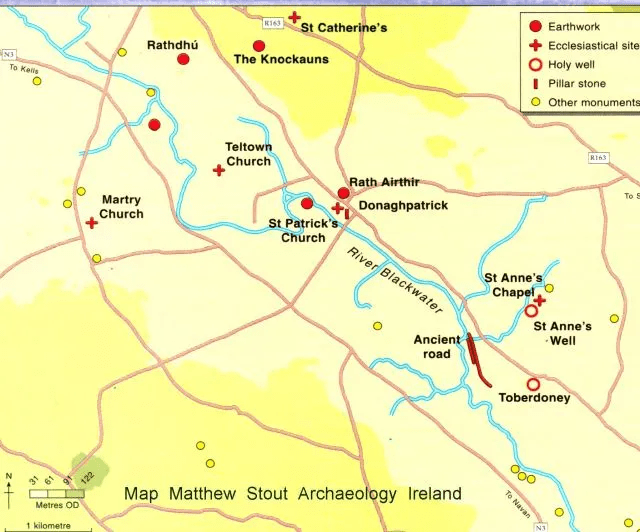

Probably the most famous of all these gatherings was the one known today as the Tailteann/Teltown Games; these may date from 1600 BC or maybe a little more recently. Given that the site adjoins Tara, the seat of the High Kings of Ireland, and that St. Patrick is said to have built a church settlement close by, the associated history/folklore was well recorded. The Tailteann Games were held each year until fairly recently. For more information on this ancient gathering, see www.navanhistory.ie/index.php?page=teltown.

Royal highways

Uisneach, (Ishnaugh) Co. Westmeath was considered to be the ceremonial, as well as physical, centre of Ireland where a great gathering took place each year to mark the feast of Bealtaine, May 1. A modern re-enactment still takes place, though now it is held on June 23 to coincide with the Summer Solstice. Some stretches of the road between here and Croagh Patrick, Co. Mayo, the seat of another great pre-Christian ceremonial gathering, are preserved to this day. This route also passed through Rathcroghan, the seat of the Kings, and the legendary Queen Meave, of Connacht. This lends credence to the belief that some of the most powerful kings cemented their alliances by attending these gatherings, travelling what were great distances in those days. The Corlea Trackway, near Keenagh, Co. Longford is a stretch of this royal highway that was built by laying timber planks to form a safe passage through bogland. There was a similar stretch from Ballintubber Co. Mayo to Croagh Patrick.

Fairs Past and Present

The following is a short list of some other famous fairs and gatherings: Donnybrook Fair, established in 1204 last took place in 1855, stopped due to excessive drinking & violence. Ballinasloe Horse Fair, Co. Galway, est’d 1722, 300 & still going strong. This is held on a hill on the outskirts of the town with all the sports and amusements that had accompanied such events from earliest times. Another such event, celebrated in song is Spancil Hill, a few miles east of Ennis, Co. Clare. Like Ballinasloe and Maam Cross, Co. Galway, this was predominantly a horse fair. Today’s fairs, here and in Maam Cross, although still attracting people from all over the country, attract significantly fewer numbers than in previous times. The Lammas Fair, Ballycastle, Co. Antrim is another which is said to date to pre-Christian times and, in its current form, is at least 300 years old.

Ceremonial Gathering Sites

There are a number of old ceremonial sites around the country which, as I mentioned earlier, were subsequently forsaken with the ascendancy of the English, and the subsequent growth of towns and villages. Ardeeara near Tubbercurry, Co. Sligo provides an example of the old ceremonial site being forsaken in favour of the newer type of market fair in the town. Traditionally the old gathering was held at Ardeeara beside Knocknashee, Cnoc na Sí, the Hill of the Fairies, a few miles from the town but moved into the town itself at some unknown time. Ardeeara was the gathering and inauguration point of the O Hara family lords of this part of South Sligo up to around the 14th Century when the Anglo Normans would have taken over. The initiation mound, where the new Chieftain/ Taoiseach would formally assume power, the site of the aonach, can still be cleary seen. As the terrain here and in Spancil Hill in particular hasn’t changed much over the centuries, it is easy to imagine the trading, sporting and other activities taking place hereand in the many other now abandoned gathering sites.

‘Beidh aonach amárach’

The aonach/fair generally was said to have three functions: honouring the dead, proclaiming laws and games and festivities. Games are said to have included long and high jump, running, hurling, spear throwing, archery, swordfighting, wrestling, swimming and horse racing. There were also competitions in singing, dancing, storytelling, and for goldsmiths, jewellers weavers and armourers. Matchmaking also featured, where couples were paired off for a year’s trial, after which they could separate if they wished.

More recent developments and changes: the market square

In the 18th and, especially, 19th century, we see the creation of a number of new towns/villages throughout Ireland. This was usually done at the behest of the local landlord, with a view to increasing income, mainly for himself, but, consequently, also for his tenants. The Market Square was usually the focal point around which the rest of the town, or village, was laid out. In the centre of the square was the weigh-house which left no room for dispute over the volume of the various commodities. These markets provided an incentive for tenants to earn some extra income to produce some extra crops, wool, linen or livestock, it also meant the landlord gained by increasing the tenant’s rent.

Close by would be a shop, pub and other business houses, which usually had accommodation attached and these also produced a further rent flow. After the easing of the Penal Laws, a church might be built, depending on how close the next nearest one was. In some few cases, landlords have been known to provide the site free of charge and even contribute to the building cost. Michael A Martin shows how Ballinamore, currently a mere crossroads, was the site of a local fair in the early 1800s when the subsequently more prosperous neighbouring villages of Ballygar and Newbridge had yet to appear on the map. These were created by local landlords later in the 1800s.

Fair Rituals

Up to the 1970s, most towns and villages had a certain number of these fairs, which had not changed substantially over the intervening centuries. These were some of the busiest days of the year for the pubs and shops and they opened far earlier than normally permitted by the licencing laws. The profit generated on these fair days, with the extended opening hours, was crucial in determining the profitability for the year. Fairs were referred to as either good, when there were a lot of buyers, demand was brisk and prices high, or slow, bad, when supply exceeded demand, and prices were low. Of course, the opposite view was taken by the buyers! There was a pre-determined ritual to be followed in the process of buying and selling. Depending on the number of buyers at the fair, and the numbers of stock for sale, a price within a certain range could be anticipated.

If a buyer/jobber stopped at your pitch, he would usually ask what price you were asking. When the seller replied, the buyer would always offer a lower amount, the seller was then expected to reduce the asking price and the buyer would, in theory, raise his offer until a compromise was agreed on. In instances where stalemate arose, a third party, often a neighbour of the seller, would intervene and help the two to reach an agreed price.

My clearest memory of a fair in Ballinrobe, Co. Mayo as a young boy is when my father met an old friend, Miko, who was selling cattle but could not get a satisfactory price. The two went for a drink, leaving Miko’s teenage son, P J, to attend to the cattle. When the father returned, the animals were sold for a price above the father’s initial opening figure. My father remarked on this many times afterwards and PJ, as it happens, went on to become a very successful and prosperous cattle dealer and transporter.

As a child it seemed to me as if the world and its mother descended on my home place on the three ‘bigger’ fair days. Some people would leave home before dawn to walk their animals to the fair and to get a spot close to the centre of the village, where they would “pen” their animals against the front of a house. Sheep and cattle would stand in pens all along the village green and on both sides of the street. As some of these sheep were of a mountainy breed, a bit wild, or bradach as we used to say, they were often tethered, having a front and rear leg tied together to prevent them escaping.

As we made our way to school, picking our way between people and animals along the street, we had to be careful not to step into the animal droppings. As well as the farmers buying and selling, there were jobbers, or livestock merchants, with their trucks, hucksters’ stalls and a caravan selling tea and sandwiches. Huckster was the name given to people who sold everything from used clothes to toys, farm tools and kitchen utensils and a lot more besides. The chain stores with their household and clothing sections were not to appear for a few more years and, anyway, cars were few and far between so travel was very limited in the early 1960s.

After hands were slapped to seal deals, and ‘luck money’ was given back to the buyer, people retired to one of the four pubs. The children who were left to tend the stock until the buyer was ready to take them away, might get a shilling or more for their troubles. This rare windfall might be used to buy a catapult or the like and maybe even have enough left for a bar of chocolate and a soft drink, which we called minerals, for some reason. Nobody wanted to be left with unsold animals, apart from not getting badly needed cash, to pay the goods they would have got on credit in the local shops, or “put in the book” as it was called back then. Neither would they want to walk them back home again, trying to prevent the poor scared creatures jumping into poorly fenced fields etc. along the miles to home. Many would accept a lower than expected price rather than be left with more stock than could easily be fed, especially when winter approached and fodder was limited.

When the last animals had gone, the walls and footpaths needed to be washed, having been decorated with lots of animal droppings. Most of the creatures would be unused to being penned and manhandled repeatedly so they tended to express their anxiety by emptying their bowels, regularly. Their mooing and bleating only added to the general din and excitement of these days that stood out to us children above the ordinariness of others. Of course their droppings had to be disposed of and so, when everyone had gone home, we’d be sent out with a bucket of water and a sweeping brush to wash down the wall and footpath until it would be “clean enough to eat your dinner off”, as we used to say. As the buying and selling finished and the crowds gradually thinned out, a sense of anti-climax seemed to descend on the whole village. After the place had been cleaned, the conversations would often turn to who got good prices and who didn’t as well as who didn’t manage to sell at all.

Feiseanna Ceoil/Irish cultural and musical events.

As the number of Irish speakers fell drastically in the aftermath of the Great Hunger (1845-52), Conradh na Gaeilge/The Gaelic League sought to arrest this decline from its inception in 1893. As well as organising Irish classes, training Irish-qualified teachers and agitating for recognition of Irish within the British controlled system, they did one other extremely important thing. They organised social events, feiseanna, to take place, initially after the language classes. These music, dance and storytelling events, through the Irish language, for many became the prime reason to attend and to celebrate their Irishness. Those who struggled a little with the language suddenly had an incentive to master a few phrases such as “Ar mhaith leat damhsa liom-Would you like to dance with me?” As more and more Conradh branches were established, the feis came to be the central social gathering in almost every area.

Even in the heart of the Gaeltacht, or Irish speaking areas, a feis could be organised at fairly short notice as a counter measure to a rival event, like a fete, where all things English would be promoted. In his book Connemara, a little Gaelic kingdom, Tim Robinson tells how Patrick Pearse orchestrated just such a situation in the rural community of Ros Muc in 1913. Pearse got to hear that the local landlord planned to have an afternoon where English songs would be sung and everything carried out as if it were in jolly old England. The local people, in deference to the English aristocrat, were expected to attend. Determined that the locals should not be subject to this feast of Englishness, Pearse immediately set about organising a feis which would prove to be not only more to the liking of the locals but also far more entertaining!! It need hardly be said that no further fetes took place in the area after this setback.

In the 21st Century, as rural Ireland has seen the closure of Gárda, (Police), stations, banks and post offices, it has been heartening to witness not only community hubs which enable shared remote working space but also the emergence of local markets in these community centres. In some cases they take place in an outdoor trading area. Their mix of crafts, food and art provide a forum for people to socialise within their own areas and re-build a sense of community. As church attendance has fallen and many small shops and fuel outlets have closed, drawing more and more commercial and other activities away from the villages, these markets have given rise to cautious optimism that all is not yet lost. Some also take pride in being able to purchase quality goods and locally produced organic food from known sources rather than the bland, preservative and sugar-laden mass-produced supermarket and online offerings.

That they can do so while arresting some of the recent rural decline is proof that when people come together as a community, they do not have to rely entirely on the political process or goodwill of the central powers in order to regain some control over their own affairs. Local producers have a new market for their vegetables, bread, cakes, arts and crafts while getting to know their neighbours better. This form of gathering provides a vital social outlet for those who might not have children in school or sporting activities or the growing number who, for drink-driving regulations or other reasons, do not frequent the local pub(s). These may lack the ceremonial grandeur of the gatherings of old and they may not match the scale and excitement of the old street fairs, which have long disappeared, but they certainly bring people together who otherwise probably would not meet in a commercial and social setting.

Tomás Ó Dúbhda grew up on the Mayo/Galway border in the 1960s. He studied Archaeology, History and Irish at the University of Galway and has maintained an active interest in each of these areas throughout his life, including the derivation of placenames, the Great Famine period, and the Land Ownership question. He has been involved with a number of heritage and historical groups, attending seminars and field trips in counties Clare, Galway, Longford, Mayo, Offaly, Roscommon, Sligo and Westmeath.