The dynamic tension between stability and change lies at the heart of rereading. (On Rereading Patricia Meyer Spacks)

A lover of books

One day my teenage son produced a drawing he had made that day in school as part of an exercise to represent your family around the dinner table without using words. The students were also asked to draw a line between them and each family member that depicted their connection – a heavy or light line, a broken line, and so on. We all laughed to see how his pesky little sister was a spiky figure and the relationship line was a shattering of sharp shards. His Dad was a bear with a heavy line depicting their strong connection. My connecting line was also heavy, but I, the mother of the house, was a book. Not someone reading a book. Just a book.

It is true. A ‘book’ sums up my life-long and ongoing preoccupation. I have been a reader as far back as I can remember. And from way back then to now, I have exasperated my family with my reply to what might I like for my birthday/Mother’s Day/Christmas: ‘a book.’ They know my taste in light reading to be autobiographies and biographies, and in fiction, novels that are lyrical and with striking landscape. I like words and imagery more than plot and character.

I have read for pleasure and for work purposes. Retirement from teaching has meant I can read just for pleasure. During Covid 19, with even more time to spare, I decided to read classics I had not read, and to reread some that I had. I was interested to see if books I had loved on a first reading when I was young, remained beloved. Some crumbled under my now jaundiced and critical eye, Wuthering Heights being one. I may have been a passionate young woman at one point and so related to Cathy, but now I find her tiresome and Heathcliffe’s masculinity I see as less virile and more toxic.

Reading and rereading

I started my classic reading with some Ernest Hemingway, and this certainly confirmed for me why he is an acclaimed writer. I had to stop reading, however, finding Hemingway’s racist language too jarring. Next was Graham Green’s Brighton Rock. Having seen the 2010 movie, I was interested in reading the novel, but this time it was references to Jews that I found disturbing. Perhaps I should begin where my novel reading began, I thought? John Steinbeck. My sister bought me a copy of Mice and Men when I was a teenager, and I was smitten with his writing, setting, and characters thereafter. I did not have any Steinbeck in my home, but I did have Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls. Steinbeck was the first novelist I followed as a teenage reader, and O’Brien was the second.

An Irish Girl

I am a child of the Irish Republic with all that that entailed, religious and societal oppression and censorship. On rereading Edna O’Brien’s, The Country Girls, I still recognised that world. I still recognised the protagonist. If on rereading Wuthering Heights I found I was no longer Cathy, I found in The Country Girls that early literary female guide in Caithleen Brady who showed my teenage heart how to find my way through the often confusing and frightening world of romantic love.

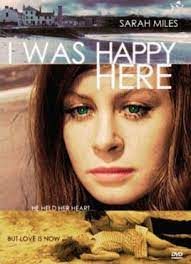

The movie I Was Happy Here (1965) was based on O’Brien’s novel, and seeing that movie led me to the novel. I was unaware of censorship of movies and novels at that time, but I can still recall the day my mother saw me reading The Country Girls and admonished me with,

‘You shouldn’t be reading that book. It’s on the Index.’

‘What’s the Index?’ (like Caithleen Brady I was interested in new words and concepts).

‘It’s a list of books banned by the Catholic Church.’

‘But I bought it in Eason’s on Saturday!’ I resumed reading.

Sensing my mother’s unease, I felt empowered for the first time in our relationship. I was becoming an independent thinker. And as I continued reading The Country Girls, I knew that I had found a literary voice that I wanted to follow, and I have done so ever since, having read all of Edna O’Brien’s novels.

I was a city girl, a Dublin city girl, and you would imagine that I would have been more sophisticated than a country girl, but I was not. Rereading The Country Girls today, I can see why it was banned in 1950s Ireland. Caithleen Brady and her friend Baba are aware of their burgeoning sexuality as early as age fourteen. I do not think I noticed this on my first reading. Rather than mooning over boys their own age, they are shown mostly reacting to approaches by older males, some of whom are married. Caithleen’s first romantic awakening is for a local married man, Mr Gentleman. I had no concerns about the marital status of Mr Gentleman on first reading The Country Girls. Not knowing anyone like him, I did not have this experience. Besides, my focus was on Caithleen, and what I could learn from her about life’s joys and pitfalls. Much, I was sure, because we had so much in common.

Caithleen is a dreamer, a reader, and looking for romance She is a wordsmith, noting new words such as ‘affectation’ and ‘mortgage.’ People are ‘lonely.’ Others are ‘lonesome.’ She has literary aspirations, that is she aspires to being in the literary world: in Dublin she buys a pair of black nylon stockings because they are ‘literary.’ She reads her English school text book for pleasure, quotes from Thoreau, and makes references to Goldsmith. She has read Dubliners and Wuthering Heights (both of which I would not read until university). She loves the farmhand Hickey and falls in love with Mr Gentleman who is always ‘gentle’ in his approaches to her.

Caithleen’s home life is unstable, with an alcoholic father who is violent towards her mother, her only other possible protector. But Caithleen has a friend Baba whose family takes Caithleen in when she can no longer live at home. Hope arrives in the form of a scholarship that means Caithleen can go to boarding school with Baba and escape village life and her threatening father.

Baba, short for ‘Bridget’ is bold and beautiful, flamboyant in action and words: ‘You’re late, you’re going to be killed, murdered, slaughtered.’ It is clear why the more introverted Caithleen is attracted to her personality, but also her more stable and luxurious home life. Baba’s father is a vet. They have a maid. Baba wears her white cardigan over her shoulders, her skin is beautiful, she is pleasantly plump, she has luxuriant black wavy hair, and, above all, exudes confidence. Caithleen by contrast is thin, undernourished, ‘ashamed’ of many things, even on seeing Baba’s parents embracing. She needs Baba because she has no one else she can trust, even though Baba is always putting her down and betraying her.

While Baba is the more dominant of the two friends, Caithleen has a quiet confidence in her ability to attract male attention in her search for romance. She knows the difference between the gauche and cack-handed approaches of the farmhand Hickey and the shopkeeper Holland, and the shyer and more gentile Mr Gentleman who also has a car and can take her for romantic drives and for afternoon tea. Mr Gentleman is part of the social elite in the village, along with the doctor’s wife and the Connors who are Protestants. He spends the weekdays in Dublin.

O’Brien does not provide a physical description of Mr Gentleman, rather, we see him through Caithleen’s emotional responses: at the village concert although she can only see ‘the back of his neck and his collar,’ she feels ‘glad that he is there.’ He, perhaps, represents the father figure she should have had. Mr Gentleman is sitting ‘next to the younger Connor girl.’ O’Brien provides this first breadcrumb for the adult reader of this man’s nefarious intentions. It is in this chapter that Caithleen learns of her mother’s untimely death, and Mr Gentleman being near at hand proves to be ‘the only one’ who can keep her’ calm.’

The novel progresses with the steady grooming of Caithleen whose heart flutters at the sound of his voice and his eyes that were ‘tired or sad or something.’ O’Brien succinctly and poignantly captures the young girl’s inarticulation when overwhelmed by emotion. He offers her his cigar. He drives fast. He invites her to ‘tea and cream-buns.’ Mr Gentleman’s ploy from when Caithleen was fourteen is to groom her until she has reached the right age and is away from parental or in locus parentis control in Dublin. In case you have not read The Country Girls, dear reader, I will not reveal any more of the novel.

Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls loses none of its charm on a reread. I have reread it twice now, finding on each read more to like: O’Brien’s attention to detail, her humour, her lyricism, the evocative landscape, the keen delineation of even the slightest characters in this rural village in 1950s Ireland, and those memorable country girls, Caithleen Brady and Baba Brennan.

Dymphna is retired with academic status from Flinders University. She is a member of the Tinteán editorial collective. An Irish language teacher in Adelaide, she has written two collections of Irish language short stories with translations. As Gaeilge was published in 2022 and Scéalta Arís in 2023. Both are published by immortalise.com.au