REVIEW by FRANCES DEVLIN-GLASS

REVIEW by FRANCES DEVLIN-GLASS

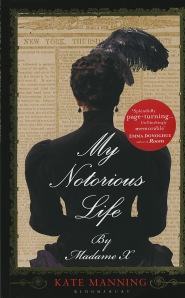

Kate Manning: My Notorious Life by Madame X, Bloomsbury, London, 2013

ISBN: 978-1-4088-3565-4

RRP: $29.99

Kate Manning in an Author’s Note identifies Ann Trow Lohman, a Gloucestershire-born emigrant to New York, as the subject who inspired her novel about a notorious midwife, purveyor of contraceptives and contraceptive advice, and procurer of abortions. For reasons which remain obscure, Kate Manning recasts her as an Irishwoman. One wonders why she effected this transformation, and the obvious reason smacks of racial profiling. In 1860s New York, to be Irish was to be poor, despised, and open to having one’s children taken away by Protestant triumphalists. The Irish dimensions of this narrative are thin and under-developed: there are trivialising allusions to beliefs in sheeogues (the sidhe) and pookas; the father is an incurable drunkard; and there is a strong emphasis on the family as tribe and an allegiance to the notion of being the children of kings. This reservation having been noted, this is an impressive and enthralling narrative.

If Dickens had been free of the restraints of respectability, and able to acknowledge honestly and frankly his own mistress, and his fascination with the underclass of prostitutes in London (whom he generously supported both financially and personally, but never wrote about), and less disenchanted with Americans, this is the kind of book he might have written. Manning does not have Dickens’ facility for comedy and caricature, but she does have a fine nose for telling detail and for grungy street-scapes, and for detailing the nefarious methods by which one might climb a greasy pole on the way to respectability of a sort.

The novel tells a compelling story of siblings separated by church-run orphanages, and the compulsion that leads them to seek continually to find one another. It is a heart-achingly tragic tale of children lured into other families by the promise of ease and luxury that is unimaginable in their birth families, but what is also made clear are the compulsions of mothers in the Victorian era to replace dead children, an all-too-common loss, with living substitutes.

The elder sibling, Ann Muldoon, who becomes Madame X (or Madame DeBeausacq) of the title, is represented as a responsible child who finds her way, without her siblings, from Ohio back to a totally incompetent and passive mother in New York, only to have her die of complications of childbirth. It is this event that sets in train a career in public ignorance-shifting in the areas of sexuality, contraception, and child-bearing. Ann Muldoon is motivated by her compulsive need to understand why her own mother died, and to prevent the circumstance where children became powerless orphans as she and her siblings had. I enjoyed the author’s subtlety and capacity to deal with complexity in the way she handles Ann being forced to question her earlier hostility to Mr Brace, the do-gooder who farmed out orphans, when she herself badly wants a second child and has to deal with a new mother’s ambivalence in giving up her newborn.

The process whereby a kitchen slave paid no wages becomes an assistant to a midwife, and, barely in her teens herself, a midwife, is made very credible in this narrative, and the grey areas between mercy and murder are minutely and carefully delineated. The child is curious, kindly, and at the mercy of a woman who subsists as a fine midwife with the help of opiates, and of course, finally succumbs to them, leaving the child-apprentice with heavy responsibilities to her clients. Manning’s proliferation of details about abortifacients, breech births, actual abortions, and curettes are to say the least grainy, graphic and compelling, especially as the prose in which they are rendered remains that of the lower-class woman she was, even after she had arrived as a very wealthy woman with a palace on Fifth Avenue. In addition to her fictionalisation of Ann Lohman, the novelist’s research gives us many other real characters of the mid-to-late nineteenth century, including C L Brace, who resettled children in new families, and Anthony Comstock, the campaigner who was ultimately successful in bringing her career in New York to a halt. She has a wealth of primary and secondary sources to draw on – advertisements, newspaper accounts of trials, and biographies, and these are assimilated into Ann’s street argot.

The personal narratives are well buttressed by an analysis of the various contexts within which Madame X’s establishment operates: she is hostage to the Social Purity campaigners who consider sex education and contraception advice as akin to pornography, and many of her grateful clients are tricked because of their own shame into unwillingly testifying against her. So, crimes not of her making are laid at her door. She was no stranger to the New York prison system, which she endured with courage and resolve. Another relevant context is that skilled practitioners like Madame X are in a contest they cannot and will not win against (male) medicos whom the clients experience as inferior.

The novel is penned with passion and very much out of a feminist consciousness. Ann’s cavalier husband, also an orphan, who disappears at crucial points (into pubs and whorehouses, one imagines), is typical of the men who attempt to impede her progress, and effectively end her career. He continually asks her to trust him, only to betray that trust, and is a chancer who is happy to live on the profits of her ideas and energy, but who cannot be a reliable bulwark because he is more driven by the need for excitement and rebelliousness than by the compassion and conviction, which drive her.

I can recommend this book: it is a page-turner and it fills out a hidden corner of the social history of pregnancy and childbirth, but don’t expect that it has much to offer by way of insight into the Irish diaspora. That is emphatically not its strength.